November 20, 2018, by Kathryn Steenson

Cheers to Nottinghamshire’s Pubs!

It’s almost that time of year when people eat, drink and make merry. Public Houses, taverns and inns have been at the centre of English community life for hundreds of years. Their origin can be traced back to Roman Britain, when places to seek rest and refreshment were established along the network of Roman roads. These spread and grew to become a focal point for socialising, eating and entertainment.

A survey in 1577 of drinking establishments in England and Wales for tax purposes recorded over 16,000 alehouses, inns, and taverns, or roughly one for every 187 people. This seems high, but official public business was often conducted in a town or village’s public house. As a well-known landmark, and a place capable of holding large gatherings, the pub would often host coroner’s inquests, military recruiting drives and property auctions. The ready availability of refreshments probably didn’t hurt, either.

Postcard of The Flying Horse, near Old Market Square in Nottingham; early 20th century. (Ref: Ottewell, David, ‘Nottinghamshire inns and pubs on old picture postcards’. EMC Pamphlet Not 1.N74 OTT)

Picture postcards were first produced in the 1890s. Many pubs and other notable landmarks were photographed and no doubt most landlords were pleased to get the publicity. Now a shopping arcade, The Flying Horse Inn’s name reflects the tradition of inns providing accommodation and stabling for travellers. It was an inn from at least 1400 until 1989 (when it became a shopping arcade) which is an impressive history but it is by no means the oldest pub. Ye Olde Salutation Inn claims that it, not Ye Olde Trippe to Jerusalem, is the oldest pub in Nottingham. In the 1990s, the University’s Archaeology Department dated timber used in the construction of the pub to about 1360, but there was probably an earlier building on the site. During the Civil War (1642-1646), both Royalists and Parliamentarians used it to recruit soldiers.

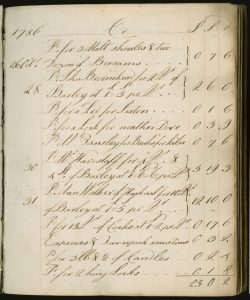

Nothing is known of Henry Daws whose name appears on the inside cover of the account book, which is dominated by payments for barley and malt. These were the two key grains used in the production of beer and ale, and it seems likely therefore that Daws was a distiller, maltster or brewer. The cash book contains details of Daws’ expenditure as well as memoranda recording what he did on particular days, with little attempt to distinguish commercial payments from other expenditure, indicating he probably owned and operated his own business.

Copy letter from Duncan Forbes, Lord Culloden to John Hay, 4th Marquess of Tweeddale; 1 January 1742. (Ref: Ne C 1610)

This letter from Scottish politician, judge and noted bon vivant Duncan Forbes discusses the state of manufacturing and revenues in Britain. He made an unusual complaint: the ‘excessive use of tea, which is now become so common that the meanest families, even of labouring people …. make their morning’s meal of it, and thereby wholly disuse the ale’. An influx of cheap tea into Scotland resulted in ale consumption dropping, which had ‘gravely affected’ excise (i.e. tax revenue). Forbes’s plan to prevent the widespread use of tea does not appear to have been a long-term success: the UK is currently the fifth biggest consumer of tea in the world, and drinking ale at breakfast is frowned upon (even at Christmas).

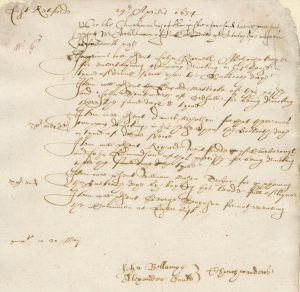

Alcohol-related offences are nothing new, despite what the media implies! In 1634 John Parnell, alehouse keeper, was summoned to the Church Courts for entertaining company drinking in his house in time of divine service on the Sabbath day; Edward Matlocke of East Retford and John Sowthworth of Ordsall for drinking there the same day and time; Daniel Nicholson for having company drinking in his house on the Sabbath day in time of divine service; Richard Whitfeilde of Clarborough and John Edmundson of this parish for drinking there the same day and time; William Mason, tailor, for profaning the Sabbath day by ‘boiling his leade full of liquor’. The only non-alcohol related offender was George Swynson, who had not received communion at Easter.

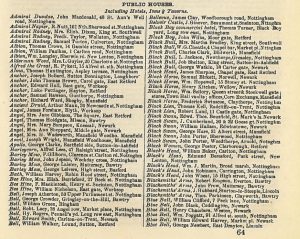

Public Houses listed in Kelly’s Directory, 1876. (Ref: Post Office directory of Nottinghamshire [Kelly’s Directory], 1876. East Midlands Collection Not 1.B15.E76)

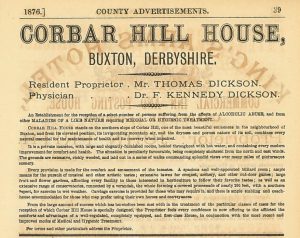

Advert for Corbar Hill House Retreat for Intemperates, 1876. (Ref: Post Office directory of Nottinghamshire [Kelly’s Directory], 1876. East Midlands Collection Not 1.B15.E76)

All these records are available to view in the Reading Room at Kings Meadow Campus. You can also follow us on Twitter @mssUninott or subscribe to our newsletter Discover.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply