October 31, 2018, by Kathryn Steenson

By the pricking of my thumbs Something wicked this way comes

The Witchcraft Act of 1735 brought an end to the legal acceptance that magic and witchcraft were genuine. It became a crime to claim magical or supernatural powers, with a maximum penalty of a year’s imprisonment. Instead, witches, cunning folk and wise men were viewed as fraudsters conning the desperate and the naïve. This complete reversal of attitude – the insistence that no real witches had ever existed – came just nine years after Janet Horne became the last person to be executed for witchcraft in the UK and overturned centuries of religious, philosophical and political writings that treated witches as a very real and dangerous threat.

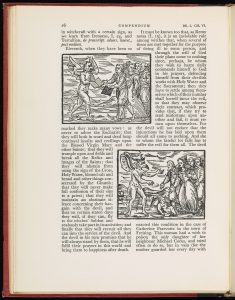

Compendium Maleficarum: collected in three books from many sources by Brother Francesco Maria Guazzo, showing iniquitous and execrable operations of witches against the human race, and the divine remedies by which they may be frustrated; 1929. Ref: Special Collection BF1559.G8

Originally published in 1608, the Compendium Malefecarium (Book of Witches) was regarded as the authoritative text on witches. Guazzo was an expert in witchcraft and demonic possession, and was highly-respected as an exorcist. The book describes witches’ pacts with the devil, their powers and poisons, and the most effective way to extract confessions and remove the spells cast by witches. The advice is supported with several examples. Many were cases Guazzo heard or read about, but given his experience, he may have included events he participated in. One such report was a “woman of fifty who endured boiling fat poured over her whole body and a severe racking….she was taken from the rack free from any sense of pain, whole and uninjured, except that her great toe had been torn off during her questioning”. The lady subsequently committed suicide in prison, which Guazzo attributes to the influence of the devil. Apparently he never considered it could be the act of a desperate woman literally being ripped apart by torturers who would never be persuaded of her innocence.

This is the earliest translation of the book into English, by an eccentric clergyman with an intense interest in the occult named Montague Summers (1880-1948). He translated several works on witches and the supernatural, and in defiance of Catholic scholars of the day, maintained that a belief in witches was compatible with and essential to Catholicism.

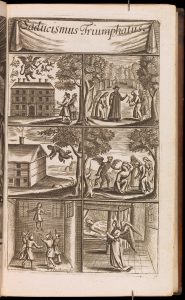

Saducismus triumphatus, or, Full and plain evidence concerning witches and apparitions, by Joseph Glanvil, late chaplain in ordinary to His Majesty, and Fellow of the Royal Society; 1689. Ref: Coleorton Parish Library BF1581.G5

Joseph Glanvill (1636-1680) was a philosopher and clergyman who was raised in a strict Puritan household. By the late 17th century skepticism of witchcraft was becoming well established, and Glanvill sought to counter this with a scientific, rational text proving not only the existence of witches possessed of malevolent supernatural powers, but also how to identify them.

The title comes from his comparison of the skeptics to the Sadducees, a Jewish sect from around the time of Jesus that did not believe in an immortal soul or an afterlife. This volume is from one of our Parish Library collections, and may well have been used as a reference by clergymen to spot any witches amongst the parishioners.

Engraving of two men, probably Macbeth and Banquo on horseback and three witches, taken from ‘Historie of Scotlande’, by Raphael Holinshed; c.1577. Ref: WLC/P/5

Finally, the source of the blog title, and something lighthearted in comparison, despite being one of Shakespeare’s most famous tragedies. Lines of text above and below the image suggest this is Macbeth encountering the three witches for the first time, when he receives a prophecy that he will be King of Scotland. Shakespeare took inspiration for the three witches from a pamphlet authored by King James VI (of Scotland) and I (of England), ‘Daemonologie’, in 1597 (institutional log-in may be required). Many of the quotes and rituals of the witches are based on those printed in ‘Daemonologie’, in part taken from the proceedings of a trial James was involved with in the 1590s that involved Scottish witches malevolently meddling with the monarch. The King was intensely concerned about the practice of witchcraft and in the early years of his reign encouraged the prosecution of witches. This official sanction, combined with his son’s tumultuous reign that ended in Civil War, possibly explains why witch-hunts in England reached a peak in the 17th century.

This volume is dated approximately 1577, which predates the play by almost 30 years. The bulk of the book may well be dated to then, but oftentimes parts of earlier books were reused in later editions. Our copy has not escaped rough treatment: some pages were removed (by order of the Privy Council) and replaced at a later date, and it has been rebound and extensively repaired over the course of its life.

All these books are available to view at Manuscripts & Special Collections. For more information or to make an appointment to view any of the material, please see our website or follow us @mssUniNott.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply