November 1, 2017, by Kathryn Summerwill

Anne Vaux: recusant!

The Seizing of Guy Fawkes, from “A Complete History of England: by question and answer: from the invasion of Julius Caesar to the year MDCCLXVI [1766]” (Briggs Collection LT109.DA/C6)

Vaux herself was arrested in March 1606 and interrogated in the Tower of London. She admitted that the plotters had visited her various houses, but was acquitted of being a part of the conspiracy and released in the summer.

After 1606, she is known to have lived with her sister Eleanor Brooksby at Shoby in Leicestershire, where they sheltered the Jesuit Father William Wright. Both sisters were convicted of recusancy (being Roman Catholic and refusing to attend their parish church) at Leicester in 1625. Anne Vaux died sometime after 1637. But this is the extent to which her biographies mention her life after the Gunpowder Plot.

However, a possible Nottinghamshire connection to Anne Vaux can now be revealed for the first time. The Archdeaconry of Nottingham Presentment bills from 1612 to 1616 consistently report the presence of a household of ‘papists’ or ‘recusants’ at Broadholme in the parish of Thorney. Broadholme was the former site of a convent of canonesses, which had been dissolved in the 1530s. It was an isolated site, perfect for concealing illegal religious practices.

The first reference comes on 27 April 1612, when the churchwardens of Thorney presented ‘Mistris Smith for an obstinate recusant, and all of her house[hold] for the like.’ (AN/PB 295/2/93). On 22 April 1613, she was named as Mris Vawse and described as a ‘papist’. (AN/PB 295/4/127). An undated bill, probably dated 1613, revealed that the churchwardens had a warrant to demand the names of the recusants at ‘Brodholme’, but that ‘they would not let us in… we could not learn any of their names.’ (AN/PB 295/4/128)

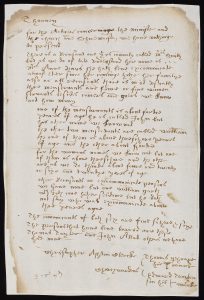

The next presentment bill, probably dated 1614, gives the most detail:

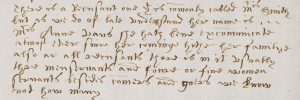

There is a recusant, commonly called Mrs Smith, but as we do of late understand, her name is Mrs Anne Vaus; she has been excommunicate almost ever since her coming here; her family also are all recusants; there are usually three menservants and four or five women servants, besides ‘comers and goers’ of we know not how many. One of the menservants is about 40 years of age and he is called John, but we do not know his other name; the other menservants are called William, one of them is above 60 years of age and the other about 40; we do not know the women’s names, but one of them is about 60 and the others about 24 or 26. (AN/PB 295/5/35)

The final document, dated 18 April 1616, names Mrs Anne Vause for a recusant. (AN/PB 295/6/22). She then disappears from the records.

The spelling of her name is variously given as Vawse, Vaus or Vause. This was a 17th-century variant for the name which is now usually given as Vaux. The behaviour of Mrs Anne Vause of Broadholme is remarkably similar to the known antics of Anne Vaux, associate of the Gunpowder plotters!

Various communities of long-established recusant families and their households were presented to the Archdeaconry court over and over again in the early 17th century. In 1605, James I’s ‘Act for the better discovering and repressing of Popish Recusants’ (3 Jac. I, iv), required churchwardens to present recusants each year. Civil courts had the power to fine recusants and to prevent them from taking up public office, but the ultimate weapon of the church courts was excommunication: not allowing the offender to take holy communion in their Anglican parish church. This was not a punishment which would deter committed Roman Catholics.

You can search the Manuscripts and Special Collections online catalogue to find out more about 17th-century recusancy. In ‘Search the catalogue’, enter the words ‘religions, Roman Catholicism’ into the Subject term field. Alternatively, in ‘Search the name index’, find ‘recusancy’ in the drop-down box next to the ‘Offence’ field.

You can also find out more about the Archdeaconry of Nottingham presentment bills in the Archdeaconry Resources part of our website.

For more information or to make an appointment to view any of the material, please see our website or follow us @mssUniNott.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply