October 26, 2017, by Kathryn Steenson

Smallpox

It has wiped out armies, killed Kings and Pharaohs, and devastated civilisations for at least 3000 (and possibly up to 10,000) years, yet the first written records mentioning smallpox only date back to 4th century China.

Trade links and the expansion of empires probably brought the disease to Europe in the 7th century, and Europeans in turn exported it to the Americas and Australia. In 1967, the World Health Organisation estimated 15 million people contracted smallpox, resulting in 2 million deaths, and yet just ten years later – and 40 years ago today, on 26 October 1977 – Somalian Ali Maow Maalin had the dubious distinction of being diagnosed with the last naturally occurring case of smallpox.

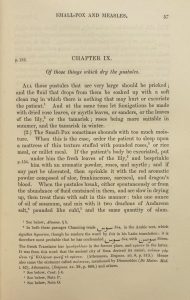

Persian physician Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (854 – 925), known in the Western world as Rhazes, was the first person to write a clinical account of smallpox and to acknowledge it as a separate disease from measles. Different chapters deal with the prevention of smallpox, the symptoms, and the different treatments and prognosis depending on the severity and location of the blisters, creating the first comprehensive manual for physicians. It was translated and published in many languages, and this volume contains numerous notes on the translation and interpretation of the original Arabic text.

Smallpox began with a fever, aches and feeling of malaise. Within a couple of days the characteristic dimpled blisters appeared, first on the face and then spreading down the body. It took two or three weeks for the blisters to heal, with the deeper lesions leaving scars on the skin. Smallpox had a mortality rate of 30%, and could leave survivors severely pockmarked and, if the sores had affected the eyes, permanently blind.

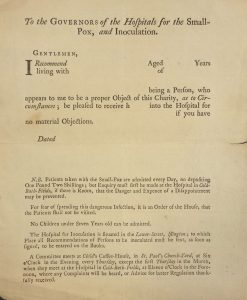

Blank printed letter of recommendation for the admission of patients to the London Smallpox Hospital in Coldbath-Fields, London, and Inoculation in the Lower-Street, Islington, London; n.d. [c. 1753-1767] Ref: WLC/X/3/2

Patients had to meet strict criteria – generally children, pregnant women, those unable to pay or who arrived outside specified hours were not admitted, regardless of how ill they were.

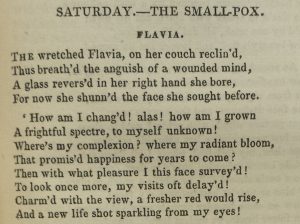

First few lines of ‘The Small-Pox’, taken from ‘The works of the Right Honourable Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’, 1825. Ref: Special Collection PR3604.A1.E25

Poet and writer Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762) was the daughter of the Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull of Thoresby Hall, Nottinghamshire. Her younger brother William died from smallpox aged 20, and Lady Mary, formerly a society beauty, was left badly scarred by the disease in 1715. She wrote this poem, ‘The Small-Pox’ a year later, lamenting her lost beauty. Whilst in Turkey with her diplomat husband, she encountered the practice of inoculation against smallpox. Pus was taken from a smallpox blister from someone with a mild case and scratched into the arm of a previously uninfected person to promote immunity. Lady Mary inoculated her children and convinced the British Royal family and doctors of the benefits. However the suspicion of ‘foreign folk-medicine’, plus the very real risk of causing a full-blown case of smallpox, meant that the practice never became widespread in Britain.

Illustration of vaccination from Jenner’s ‘An inquiry into the causes and effects of the variolae vaccinae’, 1801.

Dr Edward Jenner (1749-1823) was neither the first person to realise that people who caught cowpox from dairy herds rarely caught smallpox, nor the first to deliberately infect people with cowpox to give them immunity to smallpox. He was, however, the first person to publish his experiment. Jenner infected 8-year old James Phipps with cowpox, a relatively mild virus that causes fever and pustules similar to smallpox, but localised to the hands and arms. Once recovered, Phipps was deliberately exposed to smallpox, but did not fall ill, thereby proving that the vaccination worked.

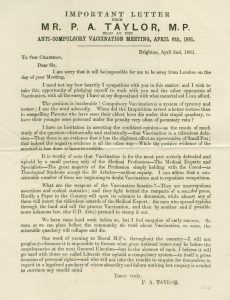

Printed letter from Mr P. A. Taylor MP concerning the anti-compulsory vaccination meeting, 2 April 1881. Ref: Ga 2 E 1905

The Vaccination Act of 1853 made it compulsory for babies born after 1st August 1853 to be vaccinated against smallpox within three months of birth. Parents who failed to do this were subject to a fine, and imprisonment if they refused to pay. Opposition over compulsory vaccination came from two directions: those who saw it as an attack on parental freedom, and those who believed, like Leicester MP Peter Taylor, that vaccination was ‘stupid quackery’. Gradually the rules were relaxed to allow conscientious exemptions, until by 1907 it was compulsory in name only. Smallpox was officially declared eradicated in 1980, less than 100 years after Taylor dismissed smallpox vaccination as a ‘ridiculous delusion’.

Manuscripts & Special Collections holds a large collection of hospital and health archives, and medical books in the Medico-Chirurgical Society Library and Medical Rare Books Collection. There are many accounts of diseases and home remedies mentioned in the personal and family papers here. For more information or to make an appointment to view any of the material, please see our website or follow us @mssUniNott.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply