June 8, 2018, by Brigitte Nerlich

Epigenetics and sociology: A critical note

I recently read an interesting article by Michel Dubois, Catherine Guaspare and Séverine Louvel entitled “De la génétique à l’épigénétique: une révolution ‘post-génomique’ à l’usage des sociologues”, which appeared in the Revue française de sociologie, 59(1), 71-98 (2018).

Dubois et al.’s ‘critical note’ is intended to introduce French readers to English works that explore the boundaries between biology and sociology. It also wants to contribute to current reflections on interdisciplinary research practices.

Five books

The article was inspired by reading five books dealing with post-genomics, epigenetics, sociology and the ‘biosocial’:

Conley, D., & Fletcher, J. (2017). The Genome Factor: What the social genomics revolution reveals about ourselves, our history, and the future. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press.

Lock, M., & Palsson, G. (2016). Can Science Resolve the Nature/Nurture Debate? Cambridge (UK): Polity Press.

Meloni, M. (2016). Political Biology: Science and social values in human heredity from eugenics to epigenetics. New York (NY): Palgrave Macmillan.

Meloni, M., Williams, S., & Martin, P. (2016). Biosocial Matters: Rethinking the Sociology-Biology Relations in the Twenty-First Century. Chichester, Malden (MA): Wiley Blackwell.

Nelson, A. (2016). The Social Life of DNA: Race, reparations, and reconciliation after the genome. Boston (MA): Beacon Press.

The article provides a detailed summary of the five books with copious quotations translated into French; but, most of all, it casts a critical eye on some of the underlying assumptions and approaches that shape them.

In this blog post I don’t want to summarise these books again, as the authors have done so well. I also don’t want to summarise the state of the art of epigenetics. I want to focus instead on the critical assessment provided by Dubois et al. and introduce English readers to this useful counterpoint to some emerging biosocial hyperbole.

Dubois et al. read the five books thoroughly, highlighting achievements and shortcomings. The most important contributions these books make to sociology is that they stimulate discussion, not only about sociology’s current relationship with biology, but also about its past relationship, a past when both disciplines were still emerging and maturing. They also inspire sociological curiosity about what’s going on in post-genomics and epigenetics (p. 91), and that can only be a good thing.

Transgenerational inheritance

Not all, but most of these books see epigenetics as a new and potentially revolutionary addition to post-genomic science. They also assume that results emerging from this new science might change the way we examine and deal with social issues like public health, but also poverty, inequality, trauma, stress, even racism, and, of course, the long-standing topic of nature and nurture, thus revolutionising medicine, social science and social policy (see p. 77).

This hope is based on the assumption that some research in epigenetics has demonstrated something called ‘transgenerational epigenetic inheritance’, i.e. “the idea that a person’s [social] experiences can somehow mark their genomes in ways that are passed on to their children and grandchildren”. This idea is then used to (a) attack the so-called central dogma of molecular biology (that genes specify the sequence of mRNA molecules, which in turn specify the sequence of proteins) and (b) give credence to some forms of neo-Lamarckism (the hypothesis that an organism can pass on characteristics that it has acquired during its lifetime to its offspring; also known as the inheritance of acquired characteristics or soft inheritance).

However, this assumption of transgenerational inheritance of social experiences provides, as yet, only rather shaky foundations for this new programme of sociological work. Some transgenerational effects have been found in plants, worms and mice, but not yet in humans, as detailed recently in a blog post by the neurogeneticist Kevin Mitchell.

This blog post appeared after the publication of the critical note by Dubois et al., but echoes their words of caution regarding the choice of scientific papers on which the biosocial programme is (perhaps prematurely) based (p. 77, pp. 87-88).

In the next few sections I’ll focus on Dubois et al.’s critique of some flaws found in some of the books they read. It is important to talk about these limitations, as these books feed into attempts at rethinking not only the relationship between sociology and biology but also between science and politics.

Whiggish fallacy

Some of the books surveyed here go deeply into the history of sociology, politics and biology and their interrelations, which is laudable. However, they sometimes adopt a style of historiography rooted in what has been called the whiggish fallacy (p. 85), that is, rewriting (or instrumentalising) the past in light (or in the service of) the present. An example is the way that August Weismann’s (19th century German evolutionary biologist) critique of Lamarckism is dissected through the lens of the modern meaning of epigenetics, not the meaning that the term had at the end of the 19th century (p. 85). In parallel with this, there is also a tendency to introduce some simplistic dichotomies (for example ‘left wing’/’right wing’) which brush over many historical complexities (p. 82). And finally, “l’eugénism n’est pas la génétique” (p. 83) – eugenics is not genetics.

Hypocritical hype

Another type of weakness lies not so much in historiographical methodology, but in a type of doublespeak adopted by some of the authors of the above books. On the one hand they warn readers against hype or the overselling of epigenetics (blamed mainly on popularisers), while on the other hand the authors themselves engage in overhyping the contribution that (what they regard as) epigenetics can make to revolutionising the sociological gaze (“’survente’ des approaches biosociales”, p. 92).

Selective attention

This is linked to another tendency displayed in some of the books, namely to pay rather selective attention (p. 87) to what actual working scientists say about epigenetics, especially their critical stance, caution and outright weariness of what is touted as the results of epigenetic research by some outliers, the same outliers that furnish the shaky foundations on which the biosocial edifice is being built.

Irenic interdisciplinarity

This brings us to the issue of interdisciplinarity and mutual engagement between natural and social scientists. Dubois et al. talk about a naively ‘irenic’ vision of interdisciplinarity (p. 88). This vision seems to promote a rather idealised and idyllic image of natural and social scientists collaborating in peace and harmony. Dubois et al. rightly point out that this ideal is rarely achieved and they will explore this topic further in the future.

Magic co-production

In the context of discussing interdisciplinarity, Dubois et al. also make some critical remarks about evoking the magic word ‘co-production’ without spelling out how this can be implemented in practice and what it means for reshaping the relations between science and politics (see pp. 82-83).

Conclusion

Overall then, when promoting a new way of studying social and scientific phenomena, sociologists, philosophers of science, political theorists and ethicists have to be careful and try to avoid what Dubois at al. call errors of ‘revision’, ‘omission’ and ‘extrapolation’ (p. 84).

(1) They need to find a sound epistemological basis on which to build their work; i.e. ground it securely in the science that studies the scientific phenomena in which they are interested. (2) They should not cherry-pick the findings that support their initial assumptions.* (3) When anchoring this new contemporary enterprise in the past, they should choose their historiographical methodology carefully. (4) And last but not least, they should not over-promise and over-hype the significance and value of this new enterprise.

People interested in thinking critically about the role of epigenetics in shaping our emerging thinking of the biosocial, should read two texts alongside this critical note by Dubois et al., namely:

Tolwinski, K. (2013). A new genetics or an epiphenomenon? Variations in the discourse of epigenetics researchers. New Genetics and Society, 32(4), 366-384.

Pickersgill, M. (2016). Epistemic modesty, ostentatiousness and the uncertainties of epigenetics: On the knowledge machinery of (social) science. The Sociological Review, 64, 186-202. [This is a chapter in Biosocial Matters]

And perhaps also:

Stelmach, A., & Nerlich, B. (2015). Metaphors in search of a target: The curious case of epigenetics. New Genetics and Society, 34(2), 196-218.

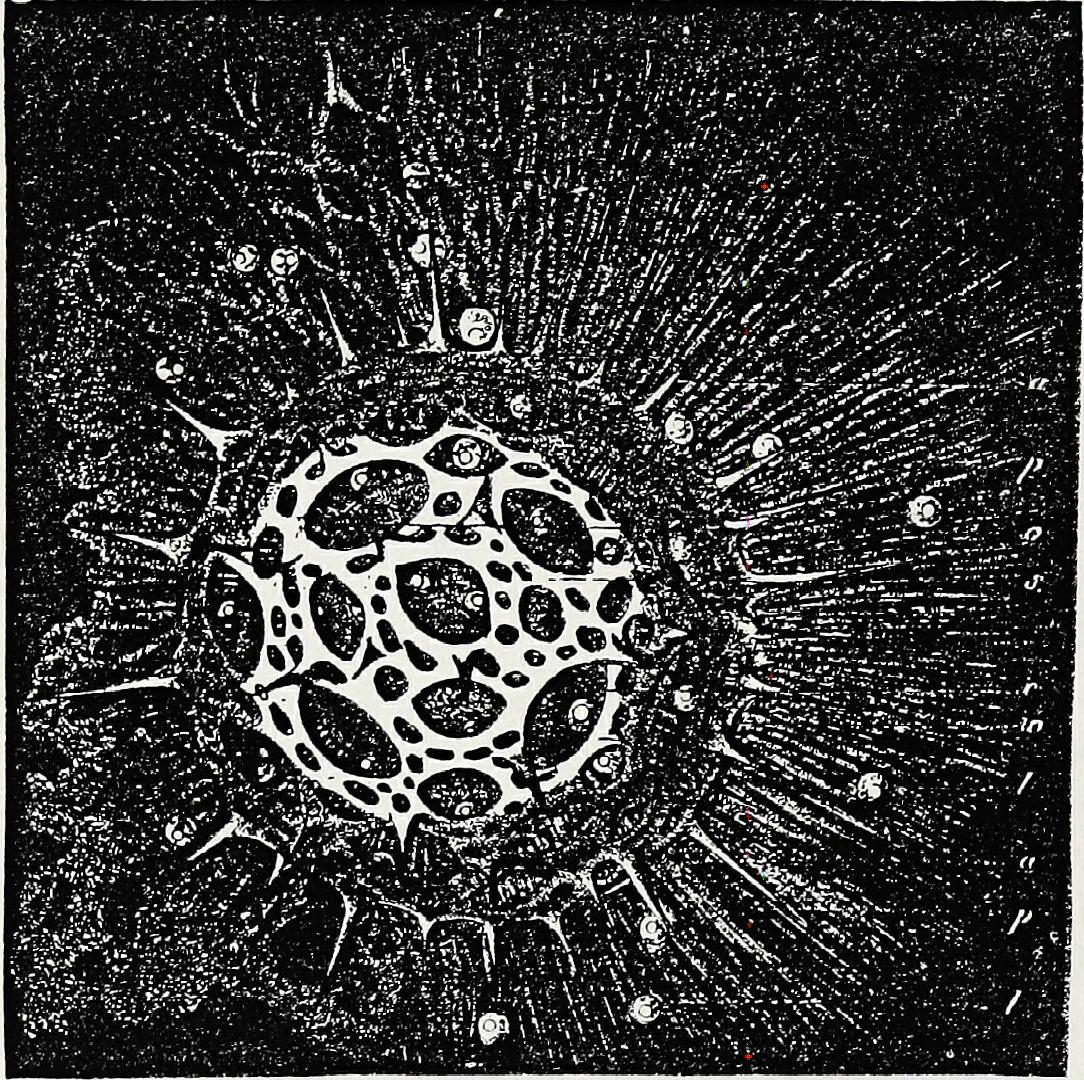

Image: from page 88 of “The history of creation; or, The development of the earth and its inhabitants by the action of natural causes. A popular exposition of the doctrine of evolution in general, and of that of Darwin, Goethe, and Lamarck in particular” (Haeckel et al., 1876)

*Of course, people can argue that I did the same when quoting Kevin Mitchell’s blog post. In my defence, I can only say that I monitored the reactions to that post on twitter and although one person called it ‘BS’, most retweeters agreed with Mitchell’s conclusions.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply