July 7, 2017, by Brigitte Nerlich

Bacteria, scientists and stewardship

Bacteria have fascinated scientists for centuries and still do. One of the first to see bacteria under the microscope was “probably the Dutch naturalist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, who in 1683 described some animalcules, as they were then called, in water, saliva, and other substances” (Encyclopaedia Britannica). A modern understanding of bacteria developed in the 19th century. Ferdinand Cohn first classified bacteria according to their size, shape and structure, while scientists like Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, “established the connections between bacteria and the processes of fermentation and disease”.

Fermentation and disease are also central to the Synthetic Biology Research Centre here in Nottingham. Some scientists at the centre use various types of engineered bacteria, mostly from the Clostridia family, to try and turn waste gases into greener, more sustainable, fuels through fermentation; others try to tackle health issues around Clostridium difficile infections and cancer by working with bacteria.

Working with bacteria and putting bacteria to work

Over the last two years or so Carmen McLeod and I, a cultural anthropologist and a linguist respectively, have observed and interviewed scientists, such as those at the SBRC for example, who work with bacteria and put bacteria to work. The analysis of Carmen’s interviews and observations has now been published in the journal Energy Research & Social Science under the title “Working with bacteria and putting bacteria to work: The biopolitics of synthetic biology for energy in the United Kingdom”.

The results of the ethnographic fieldwork show that at least some synthetic biologists face two challenges. One challenge is how to balance the curiosity-driven and intrinsically fulfilling scientific process of working with bacteria to find out how life works with the task of putting bacteria to work in order to achieve extrinsic economic value and generate growth for industry. The other challenge is how to do this within the new science governance framework called ‘Responsible Research and Innovation’ (RRI), which demands time for reflection, anticipation and debate.

Some social scientists have said that “Responsible innovation means taking care of the future through collective stewardship of science and innovation in the present.” In our article we explored the topic of stewardship more closely, both in terms of stewardship of bacteria and in terms of stewardship of scientists.

Stewardship of bacteria

For the scientists on the ground who participated in our research, the most important aspect of their work was care, stewardship, and responsibility for ‘their’ bacteria in the present, which involves giving these bacteria due respect. They also care about the near future in terms of finishing their PhDs and post-doctoral studies. Furthermore, this care of the personal present is linked to their ambition of taking care of ‘the planet’ and the more distant human future. Scientists co-opt their bacteria in efforts to carry out science that is socially beneficial; that is, in principle, they engage in RRI even without using the term.

This science stewardship (and stewardship of the bacteria) in the laboratory incorporates elements of anticipation, reflection, engagement, and responsiveness (central components of RRI) to varying degrees. There are some problems though which are related to time, space and pressure.

Local and global stewardship

We found that scientists are comfortable working at the human scale, both in terms of space and time. They assume control and responsibility over their labs and its human and bacterial inhabitants. They also carefully manage the time spent in the lab and with the bacteria and lavish as much time as possible on research and teaching activities. However, there is some anxiety when it comes to responsibility at the larger, especially the global scale, and with regard to the increasing speed and acceleration of research and innovation.

While scientists may want to ‘save the world’, they find it more difficult to create ‘wealth from waste’; while they love and value working with their bacteria and finding things out about them, they find it more problematic to put bacteria to work to create economic value; and while they readily assume responsibility for what they do in the lab, they find it harder to assume responsibility for the world at large.

Limits of stewardship

Our participants also expressed three key anxieties that impinge on their work with bacteria: (1) time pressure to produce marketable ‘products’, while at the same time reflecting on short-term and long-term risks and responsibilities; (2) the problem of ‘scaling up’ from the laboratory to the factory in a global energy market beyond researchers’ control; and (3) the perceived dilemma of engaging in public dialogue without overselling what can actually be achieved and without invoking the ‘spectre’ of another GM controversy.

There is an assumption that scientists have unfettered agency and power to embed RRI principles within their work. That is, however, not really the case. Scientists can control, to some extent, how they use bacteria for research safely and responsibly – they have power and agency in this context. Control and agency become more difficult the further away scientists get from their bacteria and labs and the more distant or abstracts risks related to their research become.

Scientists have no control or power, for example, over the world economy, oil prices and so on, which impinge on the success of fourth generation biofuels, saving the planet, and over generating growth and wealth. They have control over basic science and safety procedures in the lab. However, they find it more difficult to demonstrate control over ethical responsibilities that emerge from the RRI agenda, such as anticipating distant futures, foreseeing changes in political circumstances and making guesses about the future impacts of the science and technologies they build in the present, using bacteria in their labs.

Stewardship of scientists

RRI is based on the notions of responsibility, care and stewardship. Scientists working in synthetic biology take care of bacteria and assume control and responsibility for minimising risks to other humans and non-humans. However, their work is also controlled by various agendas, structures and systems that are beyond their control, such as the growth-agenda and the RRI agenda, which, we argue, has been largely co-opted into the growth agenda.

Surprisingly, the policy makers and funders setting these agendas do not assume the role of stewards themselves. They are, on the whole, not taking collective responsibility for the people they ‘work with’ and that they ‘put to work’. They also tend to overlook that calls for ‘scaling up’, as well as promissory discourses of profitable futures, create tensions and conflicts with the ethos and methods of science and scientists.

Policy makers and funders who impose an RRI agenda and an agenda of stewardship on scientists need to also assume responsibility for stewardship of the people they deploy.

It remains to be seen how the expectations generated by RRI can be managed in the future and how they can be collectively, responsibly and sustainably incorporated into the work of scientists and the work they make bacteria perform.

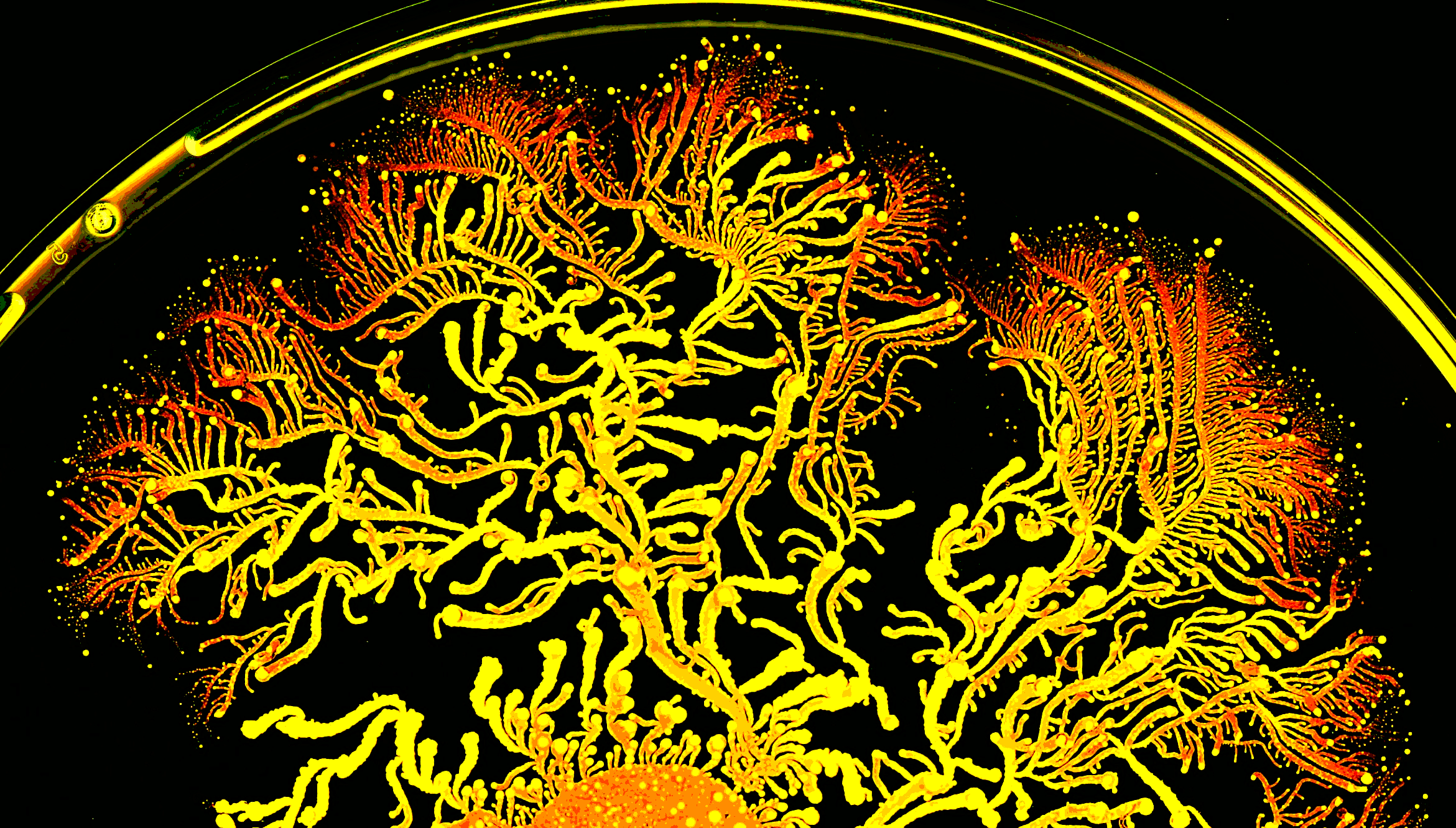

Image: The image of P. vortex colony was created at Prof. Ben-Jacob’s lab, at Tel-Aviv University, Israel) This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 License.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply