September 3, 2015, by Brigitte Nerlich

Climate wars

At the end of August Barry Woods asked on Twitter when the phrase ‘climate wars’ was first used and Warren Pearce ‘paged’ me. I was on holiday, so I didn’t have time to properly look into this. I still haven’t got a lot of time, but I have started to dig a bit.

At the end of August Barry Woods asked on Twitter when the phrase ‘climate wars’ was first used and Warren Pearce ‘paged’ me. I was on holiday, so I didn’t have time to properly look into this. I still haven’t got a lot of time, but I have started to dig a bit.

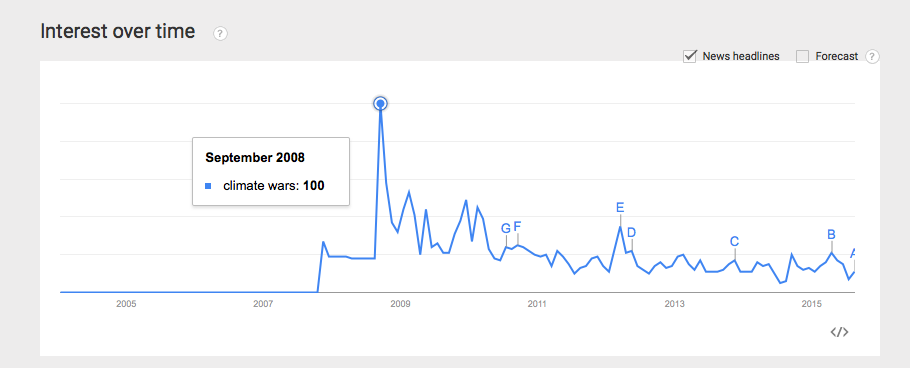

When you put ‘climate wars’ into Google Trends, which displays what people search for on Google, you see a spike in September 2008 – I’ll come back to that.

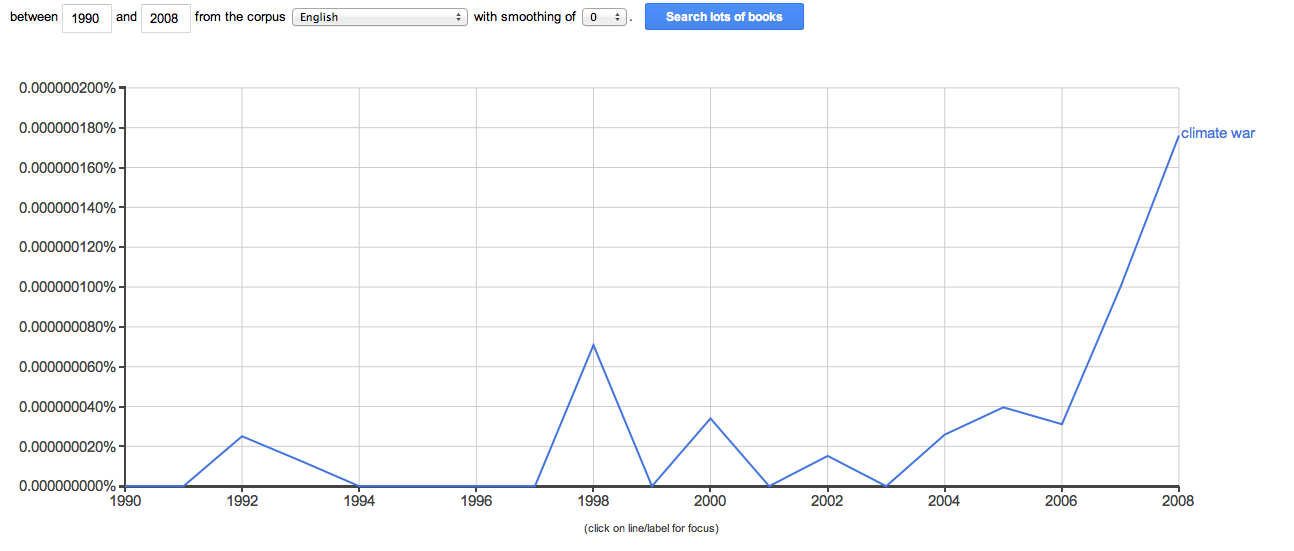

When you put ‘climate wars’ into Google Ngram viewer, which searches millions of books, you find that ‘climate wars’ doesn’t provide enough results to make a graph, but ‘climate war’ does, with a spike in around 2010

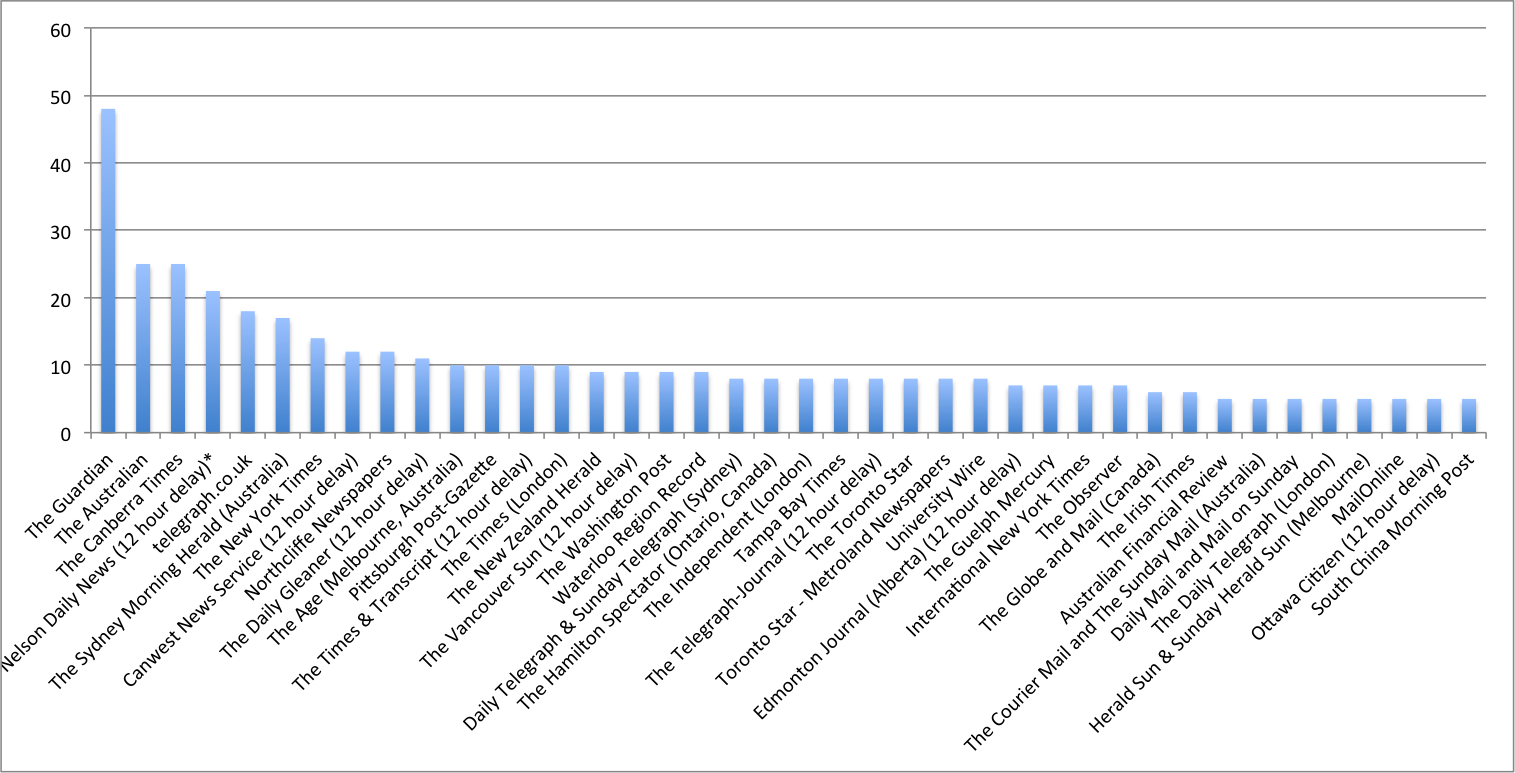

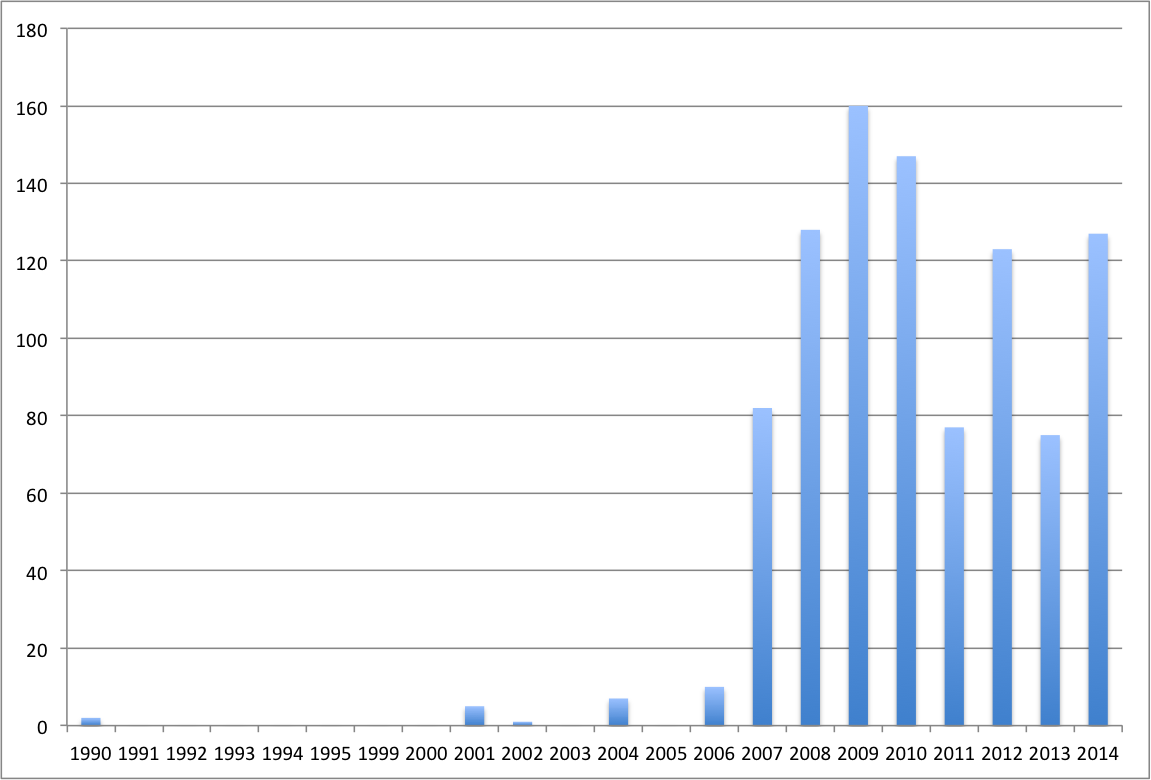

When you search Lexis Nexis, a news database, using ‘climate wars’ and ‘climate change’ or ‘global warming’ as search terms, you get 1022 results/news items (29 August, 2015). Most of the newspaper articles using that phrase appeared in either The Guardian (48) or The Australian (24) (the figure below only represents a small sample of the 628 newspaper articles in my sample, as the graph had an extremely long tail).

Most of the news items were published after 2006, as the following graph shows, with a first spike in 2007 around the fourth IPCC report, followed by one around climategate in 2009/10, then one in 2012, when Michael Mann published his book about the climategate affair, and a final one in 2014, probably due to the looming of ‘real’ climate wars.

When you go through these articles, and I have only done so very quickly, you’ll find that ‘climate wars’ has two main meanings, one based on the literal meaning of war (‘violent climate conflict’), one on the metaphorical meaning of war to describe arguments (‘violent climate debate’). There is a third meaning, which is less frequently captured by ‘climate war’ or ‘climate wars’, but pervades talk about climate change mitigation, namely, ‘combatting climate change’. This meaning mingles with the others, as we shall see.

Climate conflict

The phrase ‘climate war’ was first used on 26 May 1990 in an article for The Independent in which it was reported that “David Gee, director-designate of Friends of the Earth, said the Cold War had been replaced by a Climate War.” On 27 May The Sunday Times reported on a developing ‘green hysteria’ and referred amongst other programmes to an edition of the BBC’s Panorama programme entitled The Big Heat, which was, it seems, about “global warming and ‘the climate war'”.

Reports of such ‘climate wars’ in the sense of armed or other ‘conflict’ also appear, not surprisingly in the last article I found in my search from 1 September 2015 in Le Monde Diplomatique (English version). It is entitled “Colder, hotter, wetter, drier — and more violent; Climate change conflicts” and notes that: “Climate change refugees and war provoked or exacerbated by drought and crop failures are already with us, and they will worsen through this century.” The article also refers to a 2010 book entitled Climate Wars: The fight for survival as the world overheats by Gwynne Dyer, which “describes a world in which global warming accelerates, and refugees, hungry because of crop failures and forced to move by rising sea levels, try to reach the Northern hemisphere.”

An article in The Guardian from 24 July 2015, based on a G7 study, refers to global warming as the “ultimate threat multiplier”, but also quotes Dan Smith, secretary general of International Alert, who criticises the metaphor of ‘climate war’, “which he said had emerged in recent years, such as around the conflict in Darfur.” He warns: “It leaves out everything else – the history of rivalries, the effects of Sudan’s civil war. It reduces the relationship between climate and security to being – at its worst – the relationship between last year’s weather and war … There is a link but the complexity of it must be faced up to. We have to think about this in terms of managing the risks, not solving the problem – because the problem is already unfolding”.

This literal talk about climate wars is currently becoming dominant, gradually side-lining the metaphorical talk of climate wars between supporters and detractors of mainstream climate science. However, as we have seen, this literal type of climate war talk started as early as 1990 and was also explored in 2004, for example, in an article entitled “Science: Secretive Pentagon forecasts climate wars” (IPS-Inter Press Service, 13 February) and in 2010, when John Vidal asked in The Guardian: ‘Have the climate wars begun?’ (21 September). Five years later it seems they might have.

Climate debate

The first article to refer to the climate debate itself as a war was published on 16 March in The New York Times in 2001. It was written by Andrew Revkin and entitled “Of coal and climates”. Revking wrote: “A lack of urgency and a focus on costs both contributed to the breakdown of talks on the Kyoto in The Hague last November. The shift this week by Mr. Bush has, according to a variety of battle-worn veterans of the climate wars, threatened prospects for the next round of treaty talks, which are scheduled to take place in Bonn in July.” We’ll hear from one such battle-worn veteran in 2012.

As The Guardian and The Australian were the top two newspapers using the phrase ‘climate wars’, I looked at the first articles they published using that phrase. On 26 May 2007 David Pearce published an article in the Weekend Australian entitled “A pair of disparate shots fired in the war against global warming”. The article deals with two books, one by Clive Hamilton and entitled Scorcher: The Dirty Politics of Climate Change, the other by Murray Hogarth, entitled The 3rd Degree: Frontline in Australia’s Climate War. Hamilton used a particularly potent Australian label as he calls the oil lobby, which, according to him, stifles climate change mitigation efforts, the ‘greenhouse mafia’. The first Guardian article that makes a substantial reference to ‘climate wars’ in the sense of violent climate debate came as part of a whole batch of five ‘special reports’ published in February 2010, mainly by Fred Pearce, and dealing with the aftermath of the climategate affair.

War becomes personal

Over a hundred of the ‘climate wars’ articles in my sample refer to Michael Mann, an American climatologist implicated in the climategate affair triggered by the theft of emails from a server at the Climate Research Unit at the University of East Anglia in the UK. Mann later reflected on this whole affair in a famous book entitled The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars: Dispatches from the front lines (published in 2012). This book made the phrase ‘climate wars’ popular.

On 16 November 2011 the US Federal News published an article which reported that “Michael Mann, professor of meteorology and geosciences” and author of the then forthcoming book was to “receive the Hans Oeschger Medal from the European Geosciences Union”.

On 17 February 2012 Suzanne Goldenberg reports on his published book for The Guardian in an article entitled “The inside story on climate scientists under siege”. She wrote: “It is almost possible to dismiss Michael Mann’s account of a vast conspiracy by the fossil fuel industry to harrass [sic] scientists and befuddle the public. His story of that campaign, and his own journey from naive computer geek to battle-hardened climate ninja, seems overwrought, maybe even paranoid. But now comes the unauthorised release of documents showing how a libertarian thinktank, the Heartland Institute, which has in the past been supported by Exxon, spent millions on lavish conferences attacking scientists and concocting projects to counter science teaching for kindergarteners. Mann’s story of what he calls the climate wars, the fight by powerful entrenched interests to undermine and twist the science meant to guide government policy, starts to seem pretty much on the money”.

As one can see, the central metaphor of ‘climate wars’ is surrounded by little satellite metaphors, such as climate scientists under siege, dispatches from the front line, battle-worn veterans, and many more.

Combatting climate change

The metaphor of ‘climate wars’ with its two meanings of (violent) climate conflict and (violent) climate debate is linked to a prevailing metaphor used when talking about climate change mitigation as a war, fight or battle. One can find numerous examples of such talk, but I’ll give only one example here. This is from a 2015 article on President Obama’s Clean Power Plan: “In the fight against climate change, nothing is more important.” (The Bismark Tribune, 9 August) Interestingly, the article also refers to a 2010 book on both the climate wars covered later by Michael Mann and its repercussions on the fight to combat climate change. This is a book by Eric Pooley and entitled Climate War: True Believers, Power Brokers, and the Fight to Save the Earth.

What about September 2008?

At the beginning of this post I said that Google Trends records a spike in the search for ‘climate wars’ for September 2008. It turns out that the spike was linked to a BBC 2 programme Earth, the Climate Wars. This was a three-part series that started on 8 September 2008 and was presented by Professor Iain Stewart. Episode 1 was entitled ‘The battle begins’, episode 2 ‘Fightback’ and episode 3 ‘Fight for the future’. Here we have a mixture of all three meanings of the climate wars metaphor, but especially of the two metaphorical meanings: ‘combatting climate change’ and ‘violent climate debate’.

Interestingly, The Daily Mail reported on complaints about this programme levelled against the BBC by so-called climate sceptics in in article published on 7 January 2010. “Lord Monckton, a leading climate change sceptic, has claimed that his views have been deliberately misrepresented by the BBC. He said he had been made to look like a ‘potty peer’ on a TV programme that ‘was a one-sided polemic for the new religion of global warming’.” And here we have an example of a use of another potent ‘conceptual metaphor’ which pervades climate change debates, namely: SCIENCE IS RELIGION.

This is a topic discussed in an article by myself published in 2010 and in a more recent article by my colleagues Nelya Koteyko and Dimitrinka Atanasova who compare war and religion metaphors in the context of climate change. A good summary of their findings is provided in this New Scientist article entitled “War and religion: the metaphors hampering climate change debate”.

Conclusion

When we talk about climate wars, we deal with one literal meaning and two metaphorical meanings. In its literal meaning the phrase refers to wars and conflict provoked by climate change; in its metaphorical meaning the phrase is linked to two overarching ‘conceptual metaphors’: MITIGATING CLIMATE CHANGE IS WAR and DEBATING CLIMATE CHANGE IS WAR. The first conceptual metaphor underlies expressions such as ‘fighting against climate change’, ‘battling global warming’ and so on; the second shapes expressions such as ‘battling against mainstream science’, ‘fighting climate sceptics’ and so on. In the first case the enemy is climate change; in the second case the enemy is ‘us’ or rather two factions of ‘us’ that see each other as enemies, with what one faction may call ‘alarmists’ or ‘warmists’ on the one side of the battlefield and what the other faction may call ‘deniers’ on the other side of the battlefield, with the label ‘sceptics’ being fought over by both sides. The question now is: Does engaging in climate wars as violent climate debate distract from climate war in the sense of combatting climate change and therefore lead to violent climate wars and conflicts around the world?

Nice post..there’s a paper in this!

The whole question of tone in the climate debate is a bit fraught. My gut feeling is that everyone should be nice to each other. However, if political debates are significant then we can also expect people to be passionate and direct. So I find myself in two minds about whether or note the climate change ‘tone police’ should pipe up or pipe down (it usually seems to be the former in climate change).

For me, the problem with the war metaphor is that the one thing that does not happen in war is dialogue (at least not openly). There needs to be a ceasefire in order for that to happen. So by calling it a climate war, it suggests that there is no dialogue between opposing parties. Indeed, there should *not* be any dialogue with the enemy (or you might be taken out and shot…metaphorically at least).

One could link this to Mouffe’s ideas about democracy (developed by Amanda Machin for climate change): we should expect vigorous debate, disagreement and dissensus in a functioning democracy. However, the war metaphor implies the kind of exclusion which is dangerous to democracy.

it is usually in the extremists interests, to discourage ceasefires and people actually talking… look at pressure brought to bare by the ‘consensus police’

It is only when the extremists are sidelined, or realise they need to change to be heard any more, that progress happens. Those that have been calling others ‘climate denier’ can never acknowledge the other side, as it gives credibility that they actually might have points or be allowed at the table, and that there own actions were unreasonable.

another phrase to see when it started is ‘climate denier’ or ‘climate change denier’

throughtout the 80-90’s politicians were frequently said to be denial about global warming, (in the Kyoto does not go far enough, type context) which is much less harsh than the latter phrase..

I have found an early example, that someone claimed as the first useage, that was quite amusing (as Nottingham funded the same guy recently)

I have to confess I am grappling with the consensus issue in this context and haven’t quite found a way through that. Highlighting agreement between scientists dealing with climate change can, I think, be conceived of as encouraging a peace process, couldn’t it? By mapping fundamental agreements, a path towards further agreements can be found. This does not mean that vigorous debate should be discouraged. But all parties in the debate would have at least something to hold on to that could not be used as ammunition in a war. That a war now plays out around the consensus issue is really puzzling and rather discouraging… As for the etymology of denier, here is some info: http://www.eenews.net/stories/1060018646

It is my impression that the new interpretation of climate denier originated on DeSmogBlog in 2005 (James Hoggan) and spread from there. First mainstream usage I found was Ellen Goodman in Boston Globe 2007.

That’s interesting! They didn’t show up in my searches, which just shows that there are always limitations and that there are always gaps left for somebody more knowledgeable to fill in.

problem is if anyone actually wrote down what the scientists agreed on.. then the consensus would be shown to be a weaker thing than it is… if what the 97% of scientists actually agree on, is no longer ill (or Not)-defined, “97% of scientists” can no longer be used to say anything.

ie obama saying they (97%) agree it is ‘dangerous’ pointing to Cook’s paper, which basically said co2 is a ghg and we agree earth has warmed a bit

Hmmm I am probably an incurable idealist! Deciding to draw a clear line between saying (or agreeing on) X is happening because of Y and X is happening because of Y and, if X carries on because of Y, that’s dangerous (given the laws of physics) is, I think, a permissible inference. But I’ll leave the consensus debate to the consensus debate experts, as I bet, I got something wrong.

but the issue is how much X, and how bad is Y

not whether X or Y exists..

yep – that was the reference I was thinking of!

http://www.eenews.net/stories/1060018646

It is easier to express as two parallel theories. One is the accepted greenhouse explanation, confirmed by calculation and observation, which very few dispute. The second is newer–that atmospheric sensitivity is high and that as a result our emissions are amplified and become a threat. This has much lower levels of calculation, observations don’t really back it up and it is what the IPCC describes as the biggest unresolved issue in climate science.

Funnily enough, those skeptics and we lukewarmers who air questions about the second theory are invariably described as denying the first.