August 27, 2015, by Brigitte Nerlich

Snapshots of the unknown – some holiday souvenirs

On holiday at the English seaside I read two very different books: a popular science book on Aristotle’s biology by Armand Marie Leroi (The Lagoon, 2014) and a novel by Jules Verne about a sea voyage to the North pole (Les Aventures du Capitaine Hatteras, 1864).

On holiday at the English seaside I read two very different books: a popular science book on Aristotle’s biology by Armand Marie Leroi (The Lagoon, 2014) and a novel by Jules Verne about a sea voyage to the North pole (Les Aventures du Capitaine Hatteras, 1864).

While reading these books, I also came across an article in The Times reporting on a scientific image competition by the Royal Photographic Society which will be part of the British Science Festival at Bradford next month.

What is the common thread between these seemingly disparate reading matters? It’s images. Images are, and have always been, important to science in a variety of ways, such as: showing us the inner structure of animals and plants that we can’t otherwise see, bringing to our house representations of regions of the world that we can’t otherwise reach, and revealing to us what cannot be seen with the human eye, even if we were to cut something open ourselves or went somewhere far away to see for ourselves.

The first two functions of images have been with us for a long time (imaging something by opening it up or by going on an adventure to remote places); the third function (revealing something through new technologies of seeing) has only emerged since the invention of telescopes and microscopes in the 17th century, when Galileo showed us the surface of the moon and the moons of Jupiter and when Hooke and Leeuwenhoeck first brought to our attention increasingly close-up images of tiny animals and structures, indeed, in the case of Leeuwenhoeck, by revealing to use entirely new worlds of living creatures invisible to the human eye (see Laura Snyder’s fascinating book in this topic, which I read on an earlier holiday this year).

Living at mid-scale

Nowadays, images of the unseeable at the micro- and nanoscale have become commonplace and at the same time ‘iconic’ of what science is all about, alongside pictures of the galactic and of incredibly distant planetary objects. There is a good reason for why such images have become iconic of science. Most science is about what we can’t see or experience in everyday life using our ordinary sensory system, that is to say, things that are too small, too large, too fast or too far away (or too quantum). We live our ordinary everyday lives at the mid-scale between these extremes. Systematic scientific investigation and experimentation helps us to explore the other scales, and increasingly sophisticated technologies of scientific visualisation bring images of these explorations into our homes and into our daily lives. Now to my three texts and their images.

Aristotle – lost images of the unknown

In The Lagoon Leroi dissects and describes Aristotle’s Historia Animalum. He introduces us to how Aristotle brought order into his wealth of knowledge about the natural world, acquired either through direct observation or through listening to other people’s stories; he tells us what Aristotle got right and wrong and, most of all, he shows us how ‘science’ emerges from these efforts, especially with regard to comparative zoology. Unfortunately, many Aristotelian texts have been lost and Leroi bemoans one loss in particular: “Historia animalum lacks what any modern zoology text has: diagrams. Anatomy can’t really be learnt, or taught, without them. It is only by abstraction and visualization that the logical structure of animal form becomes clear. As any anatomist knows, you don’t really see until you draw.” Tantalisingly, Aristotle tells the readers of his Historia to consult the images/diagrams contained in eight books called The Anatomies – but these books no longer exist (p. 60).

As Leroi points out, much of what Aristotle wrote or thought can be reconstructed from other people’s quotes, but, unfortunately the diagrams and images that accompany these words are lost forever and with them our knowledge of some of Aristotle’s philosophy/zoology and of ancient anatomical drawings and drawing skills.

Verne – soon to be lost images of the unknown

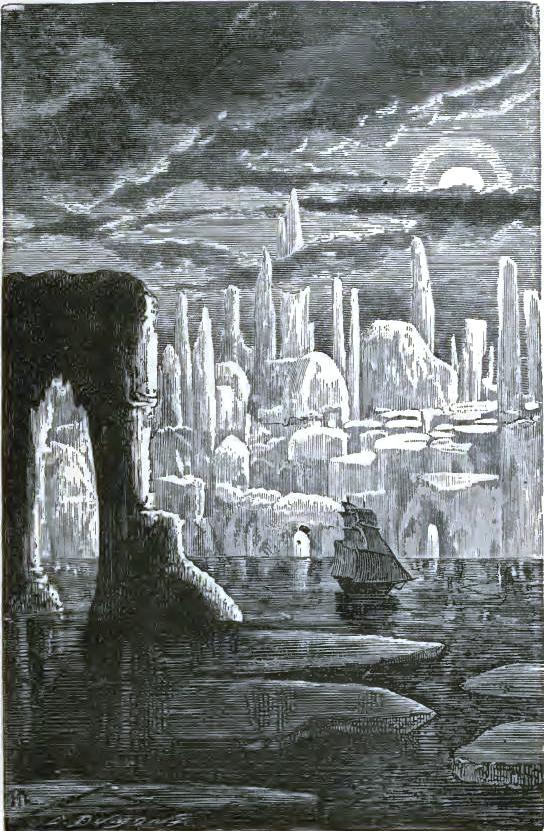

When I was reading The Voyages and Adventures of Captain Hatteras (the French version), I was struck by another real or potential loss of a different kind, but related again to images. The illustrated edition of this adventure book is full of lithographs representing not only the heroes of the book but, most importantly, what they see when venturing out to reach the North Pole by boat, leaving from Liverpool, going past Greenland, Hudson Bay, Baffin Bay, Davis Strait and so on – and what they see are all sorts of ice formations.

Like Aristotle describing an elephant’s anatomy and living habits (which he had probably never seen), so Verne had never seen these parts of the world but gathered a lot of secondhand information for his descriptions. The illustrators that worked for him got information from him and other illustrators reporting on a spade of polar explorations in the middle of the 19th century. While in Aristotle’s case images of cuttlefish or dolphins are lost, in the case of the Verne novel, I began to wonder, whether we can say that the objects of his illustrations are lost or beginning to be lost due to climate change. I have never been very far up north, but others have. Do they still encounter the ice-formations so vividly described by Verne and illustrated by Édouard Riou?

For readers of this blog who haven’t yet tasted Verne’s sometimes a bit didactic style, here is a description of various types of ice formation provided by Dr Clawbonny on board the Forward in conversation with Johnson, the the boatswain (in the French version most of the labels of ice formation are given in English):

“Very likely, Johnson; but the difficulty will be to get to Melville Bay; see how thick the ice is about us! The Forward can hardly make her way through it. See there, that huge expanse!”

“We whalers call that an ice-field, that is to say, an unbroken surface of ice, the limits of which cannot be seen.”

“And what do you call this broken field of long pieces more or less closely connected?”

“That is a pack; if it’s round we call it a patch, and a stream if it is long.”

“And that floating ice?”

“That is drift-ice; if a little higher it would be icebergs; they are very dangerous to ships, and they have to be carefully avoided. See, down there on the ice-field, that protuberance caused by the pressure of the ice; we call that a hummock; if the base were under water, we should call it a cake; we have to give names to them all to distinguish them.”

“Ah, it is a strange sight,” exclaimed the doctor, as he gazed at the wonders of the northern seas; “one’s imagination is touched by all these different shapes!”

“True,” answered Johnson, “the ice takes sometimes such curious shapes; and we men never fail to explain them in our own way.”

“See there, Johnson; see that singular collection of blocks of ice! Would one not say it was a foreign city, an Eastern city with minarets and mosques in the moonlight? Farther off is a long row of Gothic arches, which remind us of the chapel of Henry VII., or the Houses of Parliament.”

“Everything can be found there; but those cities or churches are very dangerous, and we must not go too near them. Some of those minarets are tottering, and the smallest of them would crush a ship like the Forward.”

Royal Photographic Society – iconic images of the unkown

The Royal Photographic Society is one of the world’s oldest national photographic societies, founded in 1853 as The Photographic Society of London with the objective of promoting the Art and Science of photography (see wiki). I bet Jules Verne was aware of this new source of images that he could use to inspire his stories and some of his last stories use photographs instead of lithographs. This year the society gathered 100 images that show “how little of life we see” (Oliver Moody, The Times, 19 August, p. 21) and it will display these images at the British Science Festival in Bradford.

As Richard Gray at the Daily Mail reports: “From the delicate breathing tract of a silk moth caterpillar to the sweeping majesty of the Andromeda Galaxy and the extraordinary moment an innocuous soap bubble bursts, these photographs prove that science and beauty can co-exist.” He quotes Dr Michael Pritchard, director general of the Royal Photographic Society as saying: “These images have been used to support scientific research or medical diagnosis, to illustrate learned papers and presentations, to show the places in which science is undertaken, or simply to represent the beauty that exists in the natural world and in worlds that are normally invisible to the wider public.” Have a look, especially at the image of the breathing tract of a silk moth caterpillar! I bet Aristotle would have absolutely loved that!

Seeing and living at all scales

We live our everyday life in a world of mid-scale phenomena. As part of this life we also look at images and visualisations. Using increasingly sophisticated imaging and visualisation technologies, science explores worlds well beyond the mid-scale and produces images of phenomena that are invisible to the human eye. It enables us to live, at least vicariously and voyeuristically at all scales, from the nanoscopic to the galactic, in slow motion and at high speed. Science makes these worlds public and part of our everyday world. Enjoy!

Image: Illustration by Riou for the Adventures of Captain Hatteras

Do you know Stückelberger’s Bild und Wort: Das illustrierte Fachbuch in der antiken Naturwissenschaft, Medizin und Technik?

Ah I don’t – but I’ll try to get to know it asap!! Thanks!

It’s very good

Unfortunately/disgracefully (?) it’s not in our library but I’ll get hold of it somehow!