July 23, 2013, by Warren Pearce

What’s behind the battle of received wisdoms?

This is a guest essay by Ben Pile, a writer for Spiked Online and his own blog Climate Resistance. There is a response by Dana Nuccitelli from the Guardian’s Climate Consensus blog here.

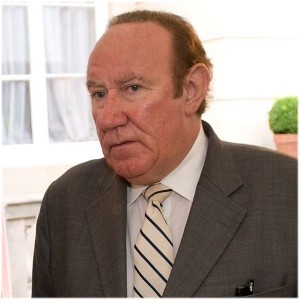

Andrew Neil’s interview with Ed Davey on the Sunday Politics show last week caused an eruption of comment. For sceptics, it was a refreshing change of scenery: a journalist at the BBC, a stronghold of environmental orthodoxy, challenging the Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change, an office which is rarely held to account. But perhaps because of this, it upset many of a greener hue.

One of these complaints was that neither interviewer nor interviewee were scientists, yet the substance of their discussion was scientific. ‘Two non-scientists discuss climate change on the Sunday Politics show‘, said Roz Pidcock at the Carbon Brief blog. At an oral evidence session of Science and Technology Committee (STC) inquiry into climate change communication last week, the issue of allowing non-expert interrogation of non-experts was raised by James Painter of the Reuter’s Institute for the Study of Journalism, and Ros Donald, also of the Carbon Brief blog — neither of them scientists, either.

Said Painter, ‘When there are really important issues like climate sensitivity to be discussed, it’s much better to have that discussion between climate scientists’. For Painter, an earlier edition of the Sunday Politics that had featured a debate between someone from Greenpeace and James Delingpole was made futile by the fact that both had, on Painter’s view, ‘agendas’. Similarly, Ros Donald told the Committee that, over Twitter, ‘There were at least five scientists offering to go on the Sunday Politics and talk to [Andrew Neil] about decadal forecasting’.

But there are very good reasons why an energy and climate change minister might make a better guest on a politics show than a climate scientist. Whereas climate scientists might well be able to explain to the viewing audience what the current state of science is, only a politician — a policymaker — can explain how advice has been taken from scientists. In the wake of a shift in climate science, it is reasonable to ask a politician how that change is to be reflected in policy.

And the science has changed. Climate advocates may want to claim that the ‘missing heat’ theory of ocean warming explains the lack of surface warming in the last decade or so. It may even turn out to be correct. But the controversial theory is still embryonic, and is a shift away from the emphasis that has been given in the very recent past to atmospheric and surface temperatures. Moreover, this revision has consequences for the estimation of climate sensitivity and its effects at the Earth’s surface — ‘impacts’ — as many scientists from across the climate debate have observed. Interviews with climate scientists on these questions might be interesting in their own right, but right now, they wouldn’t likely shed any light on the UK government’s policies.

The emphasis on expertise is either hopelessly naive or it is an attempt to delimit permissible areas of debate for strategic ends. Heaven forefend that politicians should be interrogated, lest it turn out that far-reaching and expensive policies turn out to have been, if not drafted by people who do not have a grasp of their subject, executed by them. One might be forgiven for thinking that people who emphasise the importance of scientific advice would welcome the opportunity to interrogate policy-makers’ knowledge. But instead, the attention turned to the interviewer — Neil — who now stood accused of having an agenda.

On the pages of the Guardian’s environment blog, Dana Nuccitelli (who is not a climate scientist) compiled a list of what he thought were Neil’s mistakes. ‘These are your climate errors on BBC Sunday Politics‘, he proclaimed. But half of Nuccitelli’s rebuttals related to Neil’s treatment of the study into the extent of the scientific consensus on climate change, co-authored by Nuccitelli, which represents (according to the study) the views of 97% of scientists. Davey had cited the study during the interview, but Neil had said that it had been largely discredited (Neil has just published a response to criticisms from Nuccitelli and others. Nuccitelli has responded again here).

One reason for seeing the survey through Neil’s eyes is the fact that many sceptics have pointed out that the 97% figure encompasses the arguments of most climate sceptics. In evidence to the US Senate Environmental and Public Works Committee last week, Roy Spencer, a climate scientist who is routinely vilified for his apparent climate scepticism, claimed that his arguments fell within the 97% definition. Here in the UK, climate sceptic blogger and author of the Hockey Stick Illusion, Andrew Montford tweeted in the wake of the survey, ‘isn’t everyone in the 97%? I am’. This prompted Met Office climate scientist, Richard Betts to poll the readers of the Bishop Hill blog, ‘Do you all consider yourselves in the 97%?’. It seems that almost all do.

Just as Donald and Painter’s evidence to the STC reflected either naivety or a strategy, Nuccitelli’s survey results are either the result of a comprehensive failure to understand the climate debate, or an attempt to divide it in such a way as to frame the result for political ends. The survey manifestly fails to capture arguments in the climate debate sufficient to define a consensus, much less to make a distinction between arguments within and without the consensus position. Nuccitelli’s survey seems to canvas scientific opinion, but it begins from entirely subjective categories: a cartoonish polarisation of positions within the climate debate.

Yet the survey was cited by Davey himself in defence of the government’s climate policies in the face of changing science. Whatever the scientific consensus is, the fact that this consensus can be wielded in arguments about policy without regard for the substance of the consensus creates a huge problem.

The consensus referred to by Davey and Nuccitelli, then, is what I call a consensus without an object: the consensus can mean whatever the likes of Davey and Nuccitelli want it to mean. Davey can wave away any criticism of government’s policy simply by invoking the magical proportion, 97%, even though those critics’ arguments would be included in that number. Consensus is invoked in the debate at the expense of nuance. A polarised debate suits political ends, not ‘evidence-based policy’.

Would a debate between two climate scientists, or an interrogation of climate scientists have produced anything more useful? At face value, a scientist seems less likely to make such a vapid appeal to scientific authority. But on the other hand, we often see many scientists in the climate debate doing precisely that –even chief scientific advisors — and equally failing to get a handle on the claims of climate sceptics as Davey himself. Moreover, one thing it would not reveal is the consensus without an object operating in government thinking on climate policy. Evidently, ministers are being briefed about developments in climate science partially, defensively, and strategically.

The angry exchanges on Twitter, and criticism of Neil — rather than Davey — continued. Good Science evangelist, ‘nerd cheerleader’ and ‘stats geek’ Ben Goldacre retweeted a link to Nuccitelli’s Guardian article — ‘Climate sceptic canards regurgitated by Andrew Neil get shot down, one by one’ — to his nearly 300,000 Twitter followers. Unsurprisingly, Goldacre subsequently received a number of critical tweets in reply, causing him to complain, ‘Climate bores are keen. 1 tweet, days ago, still going on about it’.

Goldacre shot to fame by denouncing TV Nutritionist Gillian McKeith and by encouraging his readers to become scientific activists in a mission to purge the public health sphere of a woo-woo tendency (homeopathy, etc). Thus, we might expect him to be more circumspect in taking a view on surveys of scientific opinion wielded in the public sphere to advance policy, and to show more grace to people who demonstrate the initiative he nurtured in his own disciples. Even more peculiarly, the ethic of disparaging those who seemingly challenge orthodox scientific thinking as ‘bores’ not worthy of engagement, would deprive Goldacre of his project’s raison d’être. The point of arming citizens with science is surely to challenge authority. Chasing homeopaths out of town: good. Challenging climate and energy ministers: bad.

Exchanges on Goldacre’s Twitter timeline may seem like so much trivia, but it nonetheless shows in microcosm how ideas about science are reproduced. The Sunday Politics episode prompted criticism from those who were concerned that Neil’s errors might influence the viewing public. But what a broader view of these debates reveal is a more troubling phenomenon of an uncritical reproduction of orthodox thinking on climate science by putative experts in science and public policy, across Twitter, the blogosphere, print media, the academy and political institutions. Physicians, heal thyselves!

So much hand-wringing about how an impressionable public might be misled by wonky graphs and hostile questioning of public figures amounts to evidence that should prompt a much more interesting study in science communication than have been produced by countless facile theories of ‘public engagement’. Shoving experts in front of cameras, hoping that it will enlighten and mobilise a largely ambivalent audience will not advance the climate policy agenda. Nor do such commentators — self-styled ‘communicators’ who believe that it will — shed any light on the relationships between government, its departments, NGOs, academia, and the media. Thus the context of the climate debate, and the expectations of climate science are excluded as subjects from the debate — a strategic move, whether or not it is intended as such. Scientism precludes sociological and historical perspectives.

The consequence of excluding non-expert opinion (other than expert opinion’s cheerleaders) from the climate debate is, paradoxically, the undermining of the value of expertise. Rather than engagements on matters of substance, a hollow debate emerges about whose evidence weighs the most, whose arguments are supported by the most experts, and which experts are the most qualified. The question ‘who should be allowed to speak’ dominates the discussion at the expense of hearing what they actually have to say.

Accordingly, rather than being a dispassionate study into scientific opinion, the 97% survey was a superficially academic exercise, intended to obfuscate the substance of the climate debate. Those who fell for it forget that its authors, aside from having their own — shock horror! — agendas, have no expertise in climate science, much less any interest in taking the sceptics’ arguments on. The emphasis on expertise is intended to permit only the expression of authorised opinion: not even the Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change is allowed to speak. Because when he does, the public debate is revealed to be merely a battle of received wisdoms.

Can we imagine this in any other discussion about public life? Should Andrew Neil be allowed to challenge ministers on unemployment figures or other economic metrics? After all, he’s just a journalist. And such hypothetical interviewees would be mere politicians, rather than ‘experts’.

Some might still sense no problem with such an expertisation of politics, and may even prefer it to what appears to be the arbitrary landscape of politics and ideology. But what the squabble over the Sunday Politics interview reveals is that political debates descend to science; they are often not improved by science and evidence as much as they degraded by undue expectations of them. Being an advocate of science seems to mean nothing more than shouting as loudly as possible ‘what science says…’, second hand.

And those who shout most loudly about science turn out to be advancing an idea of science which, rather than emphasising the scientific method, puts much more store — let’s call it ‘faith’ — in scientific institutions. Hence, the emphasis on the weight, number and height of scientific evidence articles, and expertise, rather than on the process of testing competing theories.

In spite of all the criticism levelled against him, then, Andrew Neil, in just one show, has done more to promote an active understanding of climate science and its controversies than has been done by the Carbon Brief blog, academics at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and elsewhere, Bad Science warriors, and a legion of Tweeters who claim to speak for science have done in their entire existences. Along the way, it is possible that Neil made some inconsequential technical mistakes. But by contrast, the uncritical reproduction of scientific orthodoxy is a far more egregious error: it denies that error can be observed from without the consensus. So much for ‘science’.

Comments are now closed on this article

Yes, Nuccitelli is not a climate scientist. He is an environmental scientist working for over 7 years for Tetra Tech http://www.linkedin.com/pub/dana-nuccitelli/7/a44/661 , the company that missed the Keystone XL pipeline with a nose length. See this US Congress report page 11 and 12: http://www.sanders.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Keystone%20Final%20Report%20020912.pdf

A Big Oiler posturing as a Green. Is that where this “consensus” idea comes from, because it is alien to real science?

http://ourfutures-pacificringoffire.blogspot.co.uk/

This would be one of the great answers to everything. It has got to be taken seriously.

This is an excellent article which goes straight to the heart of the matter: What happens at the science-policy interface, and how it is (not) presented to the public who pay for the science, and the policy formation, and the cost of policy implementation.

The cost of the implementation of UK climate and energy policy is not just measured in pounds sterling, but in the number of ‘excess deaths’ due to cold related diseases among the rapidly increasing number of UK citizens finding themselves thrown into ‘fuel poverty’.

what makes Dana’s and Cook survey more problematic than Doran, Anderegg Harris, Oreskes, etc is that they know their consensus is shallow encompassing the broad ranges of IPCC science on the issue (thus including the majority of sceptics)

In a topic titled, “Defining the scientific consensus,” John Cook explains:

” so we’ve ruled out a definition of AGW being “any amount of human influence” or “more than 50% human influence”. We’re basically going with Ari’s p0rno approach (I probably should stop calling it that 🙂 which is AGW = “humans are causing global warming”. Eg – no specific quantification which is the only way we can do it considering the breadth of papers we’re surveying.” – John Cook

http://rankexploits.com/musings/2013/climate-science-p0rn/

AGW with ‘No Specific Quantification’ says John Cook, will encompass all views, including Lindzen, Carter, Spencer, etc and Montford Watts, Nova, (Pile) Laframboise.

Yet we find Cook and his co-authors planning a media blitz to promote the results of the survey, before they had undertaken it. Just another soundbite to wave around, at anybody that asks any politician any questions about policy.

Dana N and John Cook found their 97% but seemed to learn nothing new about the science.

M Zimmermann, the co author of the earlier Doran ‘97% of climate scientists say’ survey that was previously waved around , seemed to have learned something new about her survey (Doran paper cited the survey produced for her Masters thesis:

http://wattsupwiththat.com/2012/07/18/what-else-did-the-97-of-scientists-say/

“This entire process has been an exercise in re-educating myself about the climate debate and, in the process, I can honestly say that I have heard very convincing arguments from all the different sides, and I think I’m actually more neutral on the issue now than I was before I started this project. There is so much gray area when you begin to mix science and politics, environmental issues and social issues, calculated rational thinking with emotions, etc.” from – The Consensus of the Consensus, M Zimmermann (Doran)

Media is all that matter for the 97% paper:

“Another co-author, Dana Nuccitelli of Sceptical Science, said s[he] was encouraging scientists to stress the consensus “at every opportunity, particularly in media interviews”. – Reuters

http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/05/16/us-climate-scientists-idUSBRE94F00020130516

stressing the consensus (media management) was exactly what Ed Davey was doing with Andrew Neill, and he had cited Cook’s paper in parliamentary speeches as well (can anybody find that linked speech) tried it against Lord Lawson aswell.

http://tallbloke.wordpress.com/2013/06/03/ed-davey-plays-the-97-consensus-trick-on-bbc-r4-in-front-of-lawson

John Cook’s (& Dana’s) motives for the survey were made clear in the leaked Skeptical Science forum comments (publically available) this comment reproduced from Lucia’s Blacckboard

Motivated by spinnability of message:

“john@skeptic (john Cook talking to Tom Curtis)

“Tom, I know how you feel as I felt some frustration when I first started rating papers, just knowing that some of them would endorse in the full paper but not in the abstract. Then I had an epiphany that set me at peace with rating papers neutral even though I knew they probably weren’t. The epiphany was that the “rating by abstract” was only the first step in the TCP campaign.

By looking at only the abstracts, we get a sense of the level of endorsement – call it an imperfect proxy for consensus in the same way that sea ice extent is an imperfect proxy for ice volume or surface temperature is a noisy proxy for heat content. What I expect to find, from my initial reconnaissance, is the # of endorsements rising exponentially over time while the # of rejections flatlines. In other words, a strengthening consensus and a growing gap between mainstream science and denial.

However, I also expect to establish quantitatively by two independent means that our estimate of the strengthening consensus is an underestimate – both by comparing our “abstract rating” to the “scientist self-rating” and your idea of a subsampled “full paper rating”. That means the result of a strengthening consensus will be robust and if it can be criticised, only for the fact that it underestimates the level of consensus.

Now my hope is that the message of a strengthening consensus makes a strong impact and a big splash and plan to network and schmooze this message out with every means at our disposal, including Peter Sinclair doing a video about the results and collaborating with Google to visualise our data (this collaboration has already begun). A strong impact will justify us going to the effort of launching “phase 3″ of TCP which is publicly crowd sourcing reading the full papers of all the neutrally rated papers, to determine more accurately which papers endorse the consensus. As the crowd sourcing gradually sifts through the papers, the level of consensus will incrementally increase and we will slowly build over time a definitive, quantitative measure of consensus in the peer-reviewed literature.

By dragging this out over time, and dribbling new updates and announcements, we also get to repeatedly beat the drum of a strengthening consensus. This project is not intended as a one-off launch but a long-game strategy with the end goal being the term “strengthing consensus” achieving public consciousness. It’s the ultimate counter-narrative to the increasingly used denier meme “the consensus is crumbling” or “scientists are mass-exodusing to skepticism”.

The psychological research tells us that a key – a deal-breaker if you will – to the public accepting climate change is an accurate perception of the scientific consensus. If the public don’t perceive a consensus, they won’t support climate policy. But we know not only is there a consensus, it’s getting stronger. This is a strong message and it is rarely presented and never quantified to my knowledge. So my hope is SkS can have a deep and lasting impact on the public perception of consensus which will make the path to climate action easier.”

http://rankexploits.com/musings/2013/i-do-not-think-it-means-what-you-think-it-means/#comment-113022

PR not science

Hi Barry, do you have a reference tor link to the importance of consensus in climate change perception. Ta 🙂

More of the spin behind the 97% paper here:

http://www.populartechnology.net/2013/06/cooks-97-consensus-study-game-plan.html

Cook:

“It’s essential that the public understands that there’s a scientific consensus on AGW. So Jim Powell, Dana and I have been working on something over the last few months that we hope will have a game changing impact on the public perception of consensus. Basically, we hope to establish that not only is there a consensus, there is a strengthening consensus. Deniers like to portray the myth that the consensus is crumbling, that the tide is turning.”

“the process of testing competing theories”

Ben Pile’s definition of science is concise and useful in deciding who is a scientist.

The theory being tested is that CO2 is causing the surface temperature to rise.

We don’t expect climate scientists to be taking the measurements themselves. The raw data and how it was got is on the net. The theory can be analysed by statistics.

Neil, a journalist and Davy, an economist work with data and analysis by statistics. They and anyone else who studies the methods can attempt scientific judgement.

Davy’s theory cannot explain the facts on Neil’s graph.

They do not want to persuade us. They want us to submit.

As Nuccitelli has made clear, there is absolutely no way that Roy Spencer would fall within the 97%. Even less so, anyone who agrees with Andrew Montford’s Bishop Hill blog. This is a massive red-herring and I am very disappointed to see this blog giving it credence. Spencer and Montford are essentially trying to argue that the 97% includes all those that admit that humans are having some effect on the Earth’s Climate. This is patently false (and I suspect Spencer and Montford know it is). As Nuccitelli says in his most recent rebutal of Andrew Neil’s (sceptic-blog-based) views:

Thanks for this comment Martin. Two quick points regarding ‘giving credence’ to Ben’s views:

1) These are Ben’s personal views, which do not represent the Making Science Public programme. Having said that, it has sparked some interesting discussions at our Science in Public conference over the last couple of days.

2) As an employee of a public university, I feel some compunction to provide a forum for discussion of key issues around science and the public. Climate change continues to provide great case studies of how these interactions in day-to-day life, of which the Neil/Davey interview (and the reaction to it) is just the latest. What is the role of science in such debates? What constitutes expertise? Where does political judgement come in? And what role should the media play in holding to account the views of the powerful in society? I would strongly argue that such questions are fundamental when thinking about science and society. Ben has a particular take on it, which many may not agree with, and he is indeed more robust in his language than many of us 😀 However, I think the piece is valuable in prompting reflection and debate around these questions, which are central to our research programme, particularly coming from a non-academic quarter.

Good quality critiques of Ben’s piece for posting on our blog are most welcome…

So “prompting reflection and debate around these questions” is “central to our research programme”? So studying the “debate” as it is doesn’t provide enough material and as a sociologist you have to step in to generate more? Is this some sort of new norm for the conduct of sociological research? Interesting if true. Reference?

Hello Steve. I am employing a variety of research methods: some quantitative which will look at data from social media and blogs. Using your phrase, perhaps that could be described as looking at the debate “as it is”. I am also using qualitative methods. Most obviously, I have spent the last seven or eight months trying to get immersed in the ‘field’ so to speak. On occasion this has included posting on here to try and get a feel for views. As I am researching scepticism in science, it seems reasonable (to me, at least) to make sure I am focusing on the issues which sceptics think are important. Whatever one thinks of the merits of such issues, part of my remit is to discover what these are. Such a bottom-up approach fits with a whole range of qualitative methods, one of the most famous being Glaser & Strauss’s grounded theory approach https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grounded_theory

Finally, I don’t have any problem with researchers generating data; participant observation is an accepted approach in the social sciences. I am less comfortable with the notion of the researcher collecting data in a value-free way (not sure if this is what you are implying). Research of *any* kind entails values. Part of ensuring research quality is being reflexive and open about these values, and to ensure that they do not engender inappropriately restrictive data interpretation.

The difficulty seems to be with the participant observation, Warren. Get too far in and your results get questioned by your peers. In this instance, I suppose you could argue that offering a venue is a trust-gaining exercise that will cause your subjects to be willing to provide you data beyond what you can gather in other ways. OTOH I think back to when I took sociology (long, long ago) and wonder what the response in the field would have been if Festinger and colleagues had gone so far as to rent an auditorium and publicize an event for those UFO nuts. That’s rather like what you just did, isn’t it (without actually becoming a participant, note)?

“As an employee of a public university, I feel some compunction to provide a forum for discussion of key issues around science and the public. (…) Good quality critiques of Ben’s piece for posting on our blog are most welcome…” But debate with the likes of Pile is of no value to either scientists or activists, is it? So, especially since Pile has no lack of other venues in which to express his views, making your stated reason rather suspect, I anticipate that one result of having taken this step will be to cause climate scientists and activists to hesitate even more to provide the participation you say you want. Perhaps you really just want it from Pile and associates, however.

Martin Lack’s comment typifies the problem of using ad-hoc and subjective categories to frame the debate. For example, “anyone who agrees with Andrew Montford’s Bishop Hill blog” isn’t really credited with having made up their own mind about either the climate debate, or what Montford has claimed. And much less are the substance of Montford’s claims engaged with. Much as a ‘consensus without an object’ operates in climate discourse, so too does a ‘scepticism without an object’ operate in argument’s such as Martin’s.

Martin seems further confused by what inclusion in the 97% means. According to the study,

“Among abstracts that expressed a position on AGW, 97.1% endorsed the scientific consensus”

The paper gives examples of statements that reflect ‘endorsement’ of the scientific consensus. They are:

(1) Explicit endorsement with quantification – Explicitly states that humans are the primary cause of recent global warming. Example: “‘The global warming during the 20th century is caused mainly by increasing greenhouse gas concentration especially since the late 1980s’”

(2) Explicit endorsement without quantification – Explicitly states humans are causing global

warming or refers to anthropogenic global warming/climate change as a known fact. Example:

“‘Emissions of a broad range of greenhouse gases of varying lifetimes contribute to global climate change”

(3) Implicit endorsement – Implies humans are causing global warming. E.g., research assumes greenhouse gas emissions cause warming without explicitly stating humans are the

cause. EXample: “‘. . . carbon sequestration in soil is important for mitigating global climate change”

Spencer’s claims are completely consistent with #2. Spencer explicitly argues that humans are causing global warming, and that it is a known fact. His main argument is about the balance of positive and negative feedback mechanisms.

As an aside, it may annoy Martin that I agree with all three, though #3 is trivial.

Nuccitelli’s rejection of Spencer’s claim to belong to the 97% somewhat proves my point about the creation of ad-hoc categories. It’s an implication that he doesn’t like. He pulls out the five papers examined by the Consensus Project, and observes that four of them take no position on AGW. A fifth was categorised: “Implicitly minimizes/rejects AGW”.

The definition of this category is

(5) Implicit rejection – Implies humans have had a minimal impact on global warming without saying so explicitly E.g., proposing a natural mechanism is the main cause of global warming. Example: “‘. . . anywhere from a major portion to all of the warming of the 20th century could plausibly result from natural causes according to these results.”

The Abstract from this paper reads as follows:

“We explore the daily evolution of tropical intraseasonal oscillations in satellite-observed tropospheric temperature, precipitation, radiative fluxes, and cloud properties. The warm/rainy phase of a composited average of fifteen oscillations is accompanied by a net reduction in radiative input into the ocean-atmosphere system, with longwave heating anomalies transitioning to longwave cooling during the rainy phase. The increase in longwave cooling is traced to decreasing coverage by ice clouds, potentially supporting Lindzen’s “infrared iris” hypothesis of climate stabilization. These observations should be considered in the testing of cloud parameterizations in climate models, which remain sources of substantial uncertainty in global warming prediction.”

This paper transparently does not take a position on AGW. The reviews were subjective. The categories were subjective. The survey is meaningless.

Spencer’s paper in the fifth category in fact belongs in the fourth, where 66% of the surveyed papers ended up.

So Nuccitelli is left with five papers that should not be included in the 97%. But non inclusion in this category is not equivalent to exclusion from it. We can only imagine that, per Nuccitelli’s claim, Spencer absolutely cannot be part of the 97% if we take for granted that the debate is one between mutually-exclusive categories. But such a complex debate manifestly cannot be reduced to such simply, binary, opposing arguments. At least, not without losing sight of its substance.

Even worse for Nuccitelli’s claim that his analysis is ‘nuanced’ is the exclusion of the 66%. This and his response to Spencer betrays his the intentions behind the survey. Either that, or he simply doesn’t understand what he has produced.

Martin, thank you for actually quoting what I wrote. This entire blog post made my head spin. After reading nearly every sentence I thought to myself “I already addressed this misconception in the articles that Ben Pile claims to be responding to.” For example, quoting Roy Spencer claiming to be in the 97% after I already pointed out that Spencer is actually in the < 3%. That's not speculation, that's where he fell in the abstract ratings. Did Pile even read my articles? I don't know if he only read a few sentences, or if he's just ignoring the inconvenient bits (like 75% of what I wrote), or what, but this post is rather appalling.

I hope I'm granted the opportunity to respond with a guest post of my own.

Dana, you will see that I have indeed read your paper. I quote it in the reply to Martin above yours:

>>So Nuccitelli is left with five papers that should not be included in the 97%. But non inclusion in this category is not equivalent to exclusion from it. We can only imagine that, per Nuccitelli’s claim, Spencer absolutely cannot be part of the 97% if we take for granted that the debate is one between mutually-exclusive categories. But such a complex debate manifestly cannot be reduced to such simply, binary, opposing arguments. At least, not without losing sight of its substance.

Even worse for Nuccitelli’s claim that his analysis is ‘nuanced’ is the exclusion of the 66%. This and his response to Spencer betrays his the intentions behind the survey. Either that, or he simply doesn’t understand what he has produced.<<

Dana you say:

Your paper had at least two definitions for category 3 minimum inclusion in the 97%:

and

Roy Spencer literally declared

That’s not speculation. He said it.

I suggest you should realise that your paper can only have so much power and then it runs out 😉

“Since we made all of our data available to the public” Except that they haven’t:

http://www.bishop-hill.net/blog/2013/7/23/keep-digging.html

Richard Tol in comment: “Cook and co have released 15% of all data requested…” (see more details there)

And because that paper classified Spencer’s paper’s a certain way – proves that he’s not part of the consensus? Maybe that paper did a bad job of classification. Certainly a number of authors have said that their views were mis-classified. Believers in AGW would like the battleground to be where they have a good chance of winning, but that doesn’t mean that it’s there.

It isn’t hard to be convinced if you just take someone’s word for it. If you want to reach the truth, it’s more work.

MikeR You believe that scientific research should be graded/rated based on the scientists beliefs??

I believe the papers were graded on the content, not on the authors belief system.

Would that offend some scientists? probably, but that is irrelevant and always has been when the greater picture is assessed.

We are talking about the physical universe, atoms etc, not a persons belief about god or what burgers they prefer.

No – instead it is being graded based on the graders’ beliefs. Nuccitelli has stated explicitly that he has a political goal from this survey: He is trying to use the consensus as a wedge to convince non-scientists about AGW. That’s what he said. Why do you trust him and his graders, and not trust the scientist’s own statements about his opinions?

Again, you’ve picked sides, you’ve decided who to believe. Your choice, but that doesn’t make it science.

Over at Bart Verheggen’s blog, on the thread ‘Consensus: Behind the numbers’

Dana Nuccitelli Says:

May 18, 2013 at 20:32

…But if a paper simply said ‘human greenhouse gas emissions are causing global warming’, that went into the endorsement category as well. After all, there’s no reason for most climate research to say ‘humans are causing >50% of global warming’ (except attribution research), especially in the abstract.

If you just want to get into the quantifications, as Bart notes, nearly 90% agreed that humans are the main cause of global warming.

———————–

96% of the papers didn’t say humans are the primary cause of the observed global warming since 1950. Any paper that said ‘human greenhouse gas emissions are causing global warming’ were assumed to mean that human emissions are the ~primary~ cause of global warming. Dana does not appear to make any bones about this. But if you’re going to simply assume that your thesis is correct a prior, there seems little point in your trying to demonstrate it in a paper.

Among the howls of outrage I think I hear a hint of desperation. A realisation of a change in the weather and that things will never be the same again for the warmists.

Since teh beginning of the global warming/climate change/climate chaos/weird weather scare, they have been used to getting a pretty free ride from the mainstream media and politicians.

No alarmist has really been publicly grilled. The IPCC has acted as a climatologist’s trade union, asked to evaluate its own members work, it has, not surprisingly given them good marks. Until recently all debate could be shut down by spurious accusations of Big Oil linked denial and /or heavy moderation of the blogosphere.

An AGW ‘narrative’ came into existence and rapidly gained influential supporters. And a ‘climate change’ industry was born and grew…and grew and grew again.

But one key player in the picture wasn’t cooperating. The central character – Mother Gaia herself. While the industry tried to convince everyone of imminent doom, she was a refusenik. And eventually her intransigence became too obvious to hide.

People began to openly wonder just how ‘settled’ the science actually was if MG’s antis were neither predicted nor explained. More adventurous people reviewed the foundations and found them shaky at best. And Climategate was a reputational disaster for all involved.

Suddenly (in relative terms) the game changed. No longer guaranteed an easy time in the mass media and realising their ‘get out of jail free card’ to any objection has past its sell-by date.

Davey’s interview was just the first of many. Ambitious journalists will have noticed. Fearful politicians too. The leaders of the Green movement suddenly see that they may well be next for the treatment. And I imagine they are all very worried. They’ve never really had to justify themselves in public before. 30 year of pat-a-cake questions from supine tame ‘environmental correspondents’ is not preparation for a good hard Neil-style interview. Think your local boys club taking on Chelsea or Bayern Munich

So what I think I hear is the desperate howl of rage saying ‘You’re not allowed to talk to us like that’

But we are. The rules have changed. And we will! Quake as you wish…….

Very well said sir !

[…] The claim has been roundly debunked. Apart from the problems with its statistical methodology, its findings are essentially meaningless. As Ben Pile points out in this characteristically measured, thoughtful piece, […]

Sorry I can’t fault Ben Pile’s piece so this probably doesn’t qualify as “Good quality critique” 🙂 But I feel I have to express my astonishment at Martin Lack’s apparent confident assertion that Roy Spencer in his eyes has now been categorised scientifically as beyond the pale and only worthy of being minimised in a debate. From his words “disappointed to see this blog giving it credence.” it seems clear that for him being seen as part of the “97%” must imbue some positive qualifying attribute, and claiming membership without qualifications is seen as some kind of theft.

What could that qualifying attribute be? I think the qualifying attribute imbued in the 97% is the right to be listened to. This should encourage more people to apply for membership.

I don’t think one needs to be in the social sciences or an anthropologist to see the fetishistic quality of 97 number. I think even nudging it up would be considered poor taste since, much like plebiscites for public approval in autocratic states, one must leave some room for plausibility 😉

It is interesting that a climate scientist like Roy Spencer’s work doesn’t make it to be part of the 97% yet, say, a paper by a haematologist who has no direct climate science qualification does. But that is just shows what science does, throw up interesting nuggets that help further our knowledge.

Is this good evidence that Spencer isn’t what he declares himself to be in his personal subjective non-peer reviewed way?

I don’t know myself. I am a layman.

So it seems to me that if Dana Nuccitelli has constructed a scientific way to say Roy Spencer is a liar and does not deserve “credence” I should just marvel at the power of science 😉

Ben says: “[Dana] simply doesn’t understand what he has produced.”

This is completely right. Dana and colleagues do not understand the forces that dragged them in the direct of their conclusions.

Well according to the leaked Skeptical Science private posts, science had nothing to do with it. John Cook was organizing a publicity campaign for the 97% consensus paper long before was he had any results. That shows the very high possibility that the results were predetermined.

Find us one single scientist that is willing to say their crisis is as real as they love to say comet hits are; as in inevitable and eventual not just another 28 more years of “maybe” a crisis as they have never agreed on anything past “could be” a crisis. Not one single IPCC warning isn’t swimming in “maybes”.

If 28 years of a “maybe” crisis is good enough for you to condemn your own kids………………..

Ben Pile is spot on. The “97% consensus” article is poorly conceived, poorly designed and poorly executed. It obscures the complexities of the climate issue and it is a sign of the desperately poor level of public and policy debate in this country that the energy minister should cite it. It offers a similar depiction of the world into categories of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ to that adopted in Anderegg et al.’s 2010 equally poor study in PNAS: dividing publishing climate scientists into ‘believers’ and ‘non-believers’. It seems to me that these people are still living (or wishing to live) in the pre-2009 world of climate change discourse. Haven’t they noticed that public understanding of the climate issue has moved on?

Hi Mike, public understanding of the climate issue is indeed moving on, notwithstanding the desire of certain near-emeritus scientists to make a second career out of contrived “debates” like the one Warren is trying to sponsor here. I refer to these interesting new poll results showing that, in the U.S. anyway, younger people are losing patience with the antics of largely elderly climate deniers. That happened a while back here in California, and was one reason for the recent near-immolation of the Republicans in California, so it’s nice to see the rest of the country starting to come along. Perhaps things are different in Britain, but I expect it to catch up with the trend soon enough, as it usually does.

Anyway, you are, unlike Pile, a scientist entirely familiar with getting published. If you really think that nearly all climate scientists don’t agree with the consensus, by all means go out and undertake research to back up your point. Until then, I’ll take your “spot on” remark as more polemical than scientific.

Steve,

I note you refer to poll results commissioned by a interested group, and that the Guardian report you link to does not name the pollster. Interestingly, the group in question, the League of Conservation Voters, also does not mention the poll on their website.

I would suggest that a poll reported, presumably at second hand, without any figures and especially details is perhaps a poor thing to cite on a scientific blog. How do you know the poll was not, as with the 97% paper, presented in such a way to produce a clear majority regardless of general neutrality? How do you know this is not a poll of LCV supporters or subscribers?

This is exactly the tendency that the original post, and Mike’s comments to which you reply, are highlighting. Regardless of how you interpret the evidence for man-made global warming (or humans affecting the climate in any way comes to that), a tendency to jump on statistics that support your view without assessing how accurate or useful they are just makes you look silly. It may be this poll is extensive, well-designed and very revealing, but until the data is analysed you can’t tell. Likewise, claiming that supporting a critique of a paper which is poorly-designed and executed is polemic rather than scientific is rather strange – Mike is clear on his objections, and your response is to try and support this ‘consensus’ paper by reference to even vaguer statistics, rather than to try and disprove his statements. That seems to be polemic to me.

We probably disagree on our interpretation of the underlying scientific evidence, but that does not mean either of us should try to use data or analysis that is weak or unsubstantiated to support a point. If there are legitimate questions about a paper (and the 97% one clearly has these) then there should be a caveat about using it – science is not about sides, but about accuracy remember.

I fear I would treat the results of a poll on the subject of AGW conducted by “The League of Conservation Voters” with a similar level of credulity as a poll on immigration conducted by the BNP.

There are plenty of other poll results that are consistent with this new one. The trend among young voters has been going on for a while. What was interesting about this poll was the elicitation of the views of the pollees. Most polls don’t do that (it’s expensive).

You mention the poll was commissioned by LCV, but fail to note that the pollsters were jointly the Democratic firm Benenson Strategy Group and the Republican firm GS Strategy Group. This sort of thing is done when people want to make sure that the results will be seen as credible by both sides in DC. You can see more detail here. If you’d like to see the crosstabs, email LCV.

Steve – my point is that the Cook et al. study is hopelessly confused as well as being largely irrelevant to the complex questions that are raised by the idea of (human-caused) climate change. As to being confused, in one place the paper claims to be exploring “the level of scientific consensus that human activity is very likely causing most of the current GW” and yet the headline conclusion is based on rating abstracts according to whether “humans are causing global warming”. These are two entirely different judgements. The irrelevance is because none of the most contentious policy responses to climate change are resolved *even if* we accept that 97.1% of climate scientists believe that “human activity is very likely causing most of the current GW” (which of course is not what the study has shown). And more broadly, the sprawling scientific knowledge about climate and its changes cannot helpfully be reduced to a single consensus statement, however carefully worded. The various studies – such as Cook et al – that try to enumerate the climate change consensus pretend it can and that is why I find them unhelpful – and, in the sprit of this blog, I would suggest too that they are not helpful for our fellow citizens.

Mike

p.s. I’d be interested to know what Emeritus Chair I’m about to be offered!

Hi Professor Hulme,

As a coauthor of the paper in question, I thought I might respond.

“The irrelevance is because none of the most contentious policy responses to climate change are resolved *even if* we accept that 97.1% of climate scientists believe that “human activity is very likely causing most of the current GW”

“I would suggest too that they are not helpful for our fellow citizens.”

There is a growing body of published and in progress studies that in fact demonstrate that simply communicating the consensus not only moves public opinion into better alignment with the scientific community, but also increases public support for taking action on climate change- in other words, the opposite of what you’re implying here.

I find your comments, in light of this research, to be disappointing, as it seems that you are either unaware of it (in which case I am puzzled as to why you have weighed in on this topic) or are doing the very thing which you seem to be accusing Cook et al. of- namely ignoring the socio-political dimensions of the issue beyond the physical science consensus.

I’d be most grateful to hear your response to my comment.

Best,

Peter

Peter, your view is a commonly held one among enthusiastic young activists but it is completely wrong. In addition to Mike Hulme’s comments, see also this post from Science communication expert Dan Kahan, where he is very cynical about the idea that declaring a scientific consensus will convince the public.

http://www.culturalcognition.net/blog/2013/5/17/annual-new-study-finds-97-of-climate-scientists-believe-in-m.html

Kahan links to Keith Kloor, who in turn links to David Appell, all saying much the same thing.

Mike, I agree that such studies aren’t terribly helpful with the general public. They are a good tool for combating false balance and for persuading policymakers, though (in combination with the ARs and similar). As for the details being arguable, well, it’s social science so that’s always going to be true. I do find it interesting that you want to spend time arguing about such things even though you have much more direct evidence of the views of the vast majority of climate scientists. What’s the point?

Or putting it another way Steve – “Poll shows under 35 yr olds more susceptible to idealistic, liberal propaganda”.

Sound like more ursine defecatory research to me.

Hmm…

Many of the above comments seem to be aimed at determining which club an individual belongs to – decided by their faith in one set of scientific papers or another.

I am a simple member of the public, without formal qualifications in climate science. According to some views, that does not entitle me to believe anything, and I should just accept what I am told (and pay as required). But it seems to me that, as soon as I am asked to pay for the political policies which are generated by this controversy, I should have just as much right to an opinion as the most qualified specialist. Surely it is up to that specialist to convince me to spend my money, on my terms rather than his, before I am required to part with it?

For the record, my current beliefs are that extra CO2 can certainly enable an air mixture to absorb more radiation in laboratory conditions. So I ‘believe’ in the ‘greenhouse effect’. But I also consider that the Earth has massive, poorly understood negative feedback processes which act to maintain equilibriums of all kinds, and so the extra CO2 generated by man does not create a ‘tipping point’ but is rather lost in the noise as far more massive CO2 sinks and sources operate. Furthermore, any slight temperature variation is also acted upon by negative feedback processes – albedo and thunderstorms, to name a couple, so that temperature is not driven by CO2 concentration at all.

Where does that put me with respect to the 97%?

Dodgy Geezer, you are clearly part of the 97%. You are also more sceptical than a lot of sceptics.

For several years my 30 second answer to “What do you think of Global Warming” has been

1. It’s real.

2. It is likely exaggerated by a factor of 2.

3. Our understanding of climate is not as good as is being claimed.

4. The negative effects of global warming have been exaggerated and overdramatised.

5. Any positive effects of warmng are ignored, or at least minimized.

6. There is a stronig possibility that “the cure is worse than the disease”

Well, I am left in the interesting position of believing that:

a) the CO2 radiation absorption and re-emission process works as specified, but

b) Anthropic CO2 emissions have essentially NO impact on the Earth’s climate.

which is not a position I have ever seen proposed – but which is far more consistent with current observations than the outputs from the GCMs.

I came to this argument around 2000 when I noticed the discussion between Mann, Nature and McKitrick/McIntyre over the use of off-centred PCA in the hockey-stick graph. I looked at the maths – it seemed obvious that Mann et al 98 was wrong – indeed, it looked intentional rather than a mistake. And yet Nature was suppressing discussion?

I looked further and found John Daly’s excellent blog which documented exactly the same refusal to engage on the part of the establishment over sea levels when clear errors were pointed out. And it’s just gone on from there….

I think it’s more the other way round. Eventually the States will catch up with Britain’s now lively and increasingly open science and policy debates, in which the pathetic insults of the sort hurled up by Mr Bloom are thankfully on the wane.

Greenhouse gas theory as extrapolated to the actual atmosphere (as opposed to bell jars) relies on an ‘all else being equal’ argument.

Newsflash: It isn’t.

Nature is now performing the crucial experiment for us:

During the late C20th Temperature rose, CO2 levels rose and the Sun’s output was well above the longterm average.

In the C21st, CO2 levels continue to rise, the Sun has gone sleepy and the temperature rise has levelled out and started to fall slightly.

No exhorbitantly expensive and economically destructive mitigation policy can be legitimately pursued until nature has been given at least decade to show us the outcome. This is because the true error ranges on our measurements of solar activity, top of atmosphere energy balance and ocean heat content are such that we cannot be sufficiently certain of the correctness of the theory to act precipitately or on the ‘precautionary principle’, which if valid, would need to be applied to itself…

re Steve Bloom’s elderly climate deniezers, this Mark Twain quote springs to mind:

“When I was a boy of fourteen, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be twenty-one, I was astonished at how much he had learned in seven years.”

The question is how much he retained by age 65 or so. People do seem to become less willing to accept new ideas and change by the time they get that old even while ego attachment to being right increases. Imagine that.

Sounds a lot like James Hansen.

Sounds a lot like Steve Bloom.

My elderliness helped me realise that the enthusiastic agenda driven half truths about AGW promoted by 35 year old kids was just that.

Steve,

I assume you are therefore saying that no scientist has anything valid to say once they are over something like 50? 45?

Whilst you would have a case if you said most scientists do their most striking work relatively young, I don’t think you have met many scientists if you think the old ones are the more dogmatic – the ability to survive in universities/research companies tends to favour pragmatism and sensible views over dogmaticism and extremism.

Actually, what you tend to find is older scientists have seen it all before – they’ve lived through various phases of media interest, public policy intervention and even consensus, and are more willing to disbelieve it through experience. And being an emiritus does make you more likely to oppose a consensus than being a young researcher looking to have a career. The biggest danger to science of any sort is the idea that there is a right and wrong answer – it forces people who wish to be scientists to follow a set of beliefs even if they have reason to question them. Imagine a world where creationalism was the consensus (as a lot of strange people seem to wish to bring about), and you might see the problem…

We all know that Neil would have looked into the science and seen that the ‘pause’ is really just caused by weather! You all think it’s ok to mislead the public like that? As stated in Foster and Rahmstorf 2011 Environ. Res. Lett. ‘When the data are adjusted to remove the estimated impact of known factors on short-term temperature variations (El Niño/southern oscillation, volcanic aerosols and solar variability), the global warming signal becomes even more evident as noise is reduced.’

Even (un)Skeptical Science has (to its’ credit) backed off support for the Foster and Rahmstorf 2011 paper, pulling a video from YouTube and stating that it no longer represents the scientific consensus.

Neil and his staff did an internet paperchase and picked up anything that had a hint or smell of climate denial.

But Neil did not have the balls to use it in a discussion with a scientist. He used it against a politician in what was a blatant attempt at an on-air ambush.

Unluckily for him, Ed Davey was well able to manage.

Back to the Drawing Board, Andrew.

Yep. You’re right of course.

What an underhand tactic that a guy who presents a show called ‘Sunday Politics’ should try to discuss climate matters with the Minister of Energy and Climate Change!

How can he possibly be expected to know anything about the basis of a programme where he’s spending £400,000,000,000 of our money? Quite unreasonable.

The public have a well-defined role in the climate discussion. It is to And to do what climatologists say. Shut up and cough up.

/sarc

Dodgy Geezer,

You state, “But I also consider that the Earth has massive, poorly understood negative feedback processes …..”

This is true to an extent (had ‘potentially’ been placed in front of ‘massive’ it would be correct), and it is likely that it will be the interplay of feedbacks that determine what kind of Earth we end up with. However, it is not the whole story. Earth has potentially massive, poorly understood positive feedbacks too, which you fail to mention. Albedo loss, permafrost melt leading to methane release and so on. If we are going to have this debate, it is necessary to look at all aspects of it.

You ask why I do not mention positive feedbacks.

I am talking about my beliefs, since this is a field where the science is definitely not settled, for all that a group of activists would like to claim that it is. There is no point having a debate about beliefs, since these are by definition personal prejudices. But I can indicate two reasons why I hold the beliefs I do.

1 – The Earth has maintained the same temperatures, within a few degrees, for virtually all of its existence. I say temperatures, because we seem to live on a 2-state planet – short temperate periods, interspersed with long Ice Ages. But there is no indication of the runaway heating which would result from ‘potentially massive positive feedbacks’. So I don’t think that they exist.

2 – The second reason is shorter. It is simply that I have, in general, found the believers in AGW to run science as an activist process. They distort arguments, they try to suppress disagreement, they produce fraudulent work and try to conceal any shortcomings in their position rather than openly discussing them. The public may not understand complex statistical manipulation of proxies to extract signal from noise, but they can certainly spot when they are being lied to. And that is probably the main reason for the failure of ‘Global Warming/Climate Change’ advocacy to connect with the public at large…

As your point 1 is largely wrong, possibly point 2 is self-referential?

You could look this stuff up on the internet, but just to start, for most of the Phanerozoic (the last half billion years or so) there have been 2 states, mainly ice-free but with short periods of glaciation. We’re in one of the latter now. Pleistocene CO2 was the lowest of the Phanerozoic, and not uncoincidentally it appears to have been the coldest as well (hard to know for sure since the only comparable glacial period was the Ordovician ~400 mya, really a different planet in climate terms).

In the Pliocene, a little more than 3 million years ago, very recent times in geologic terms, CO2 was ~ same as current, temps were 2-3C above pre-industrial (*much* warmer polar regions, with beavers and camels living on northern Ellesmere Island), and sea levels were + ~25 meters above present. See here for the details. Keep CO2 at current levels, and in a few thousand years the climate would transition to those conditions. But of course we are not staying at those levels, so absent immediate sharp action your descendants, if any, can expect a very rough ride indeed.

You’re welcome.

Umm… you tell me that point 1 is largely wrong, and then confirm that it is true. Why is this? And since CO2 has never been seen to drive temperatures, but rather follow them, I can’t see how keeping CO2 levels high (always supposing that we found a way to do this) would result in higher temperatures….

As for point 2, I’m not the one hiding the Yamal series…

Wow, a total lack of reading comprehension:

You said “short temperate periods, interspersed with long Ice Ages.”

I said (supported by the scientific evidence) “mainly ice-free but with short periods of glaciation.”

IOW the exact opposite. (And BTW those ice-free periods weren’t any sort of “temperate” climate we would recognize.)

What else are you wrong about?

What about the Carboniferous Visean and the Gondwana Continental Glaciation at the South Pole?

This glaciation occurred at a time when the planet experienced both ice cap controlled eustatic sea level variations in the marine deltaic Yoredale equatorial coal deposits of Yorkshire while at the same time sapropel deposition associated with ocean warm water anoxia occurred in deep sea marine shales.

In the Visean planetary Ice-house world and Green-house world conditions occurred at the same time along with high atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide gas.

Toby:

Actually, they sniffed around the CRU’s website and found Phil Jones graph of global surface temperature, and used it to quiz Davey with. Fancy using real data from an official source like that. It’s nothing short of low down mean dirty tricks is it?

Rag Tallbloke. It is wrong when used out of context! It’s raw data that has no meaning if it is not explained. You do understand that, right?

Michael, the Phil Jones graph used in the interview was not raw data. Explaining it was what Andrew Neil was inviting Ed Davey to do. Ed Davey made an appeal to a recently added ad hoc addition to global warming theory to ex plain the flattening of the temperature curve since 1997.

Thanks for comments all. However, please note personal insults will be deleted 🙂

Mr. Pearce, thanks for this thread, it has been interesting. As a member of the audience watching this debate for over 10 yrs, it seems to be more balanced and factual than in the past. I must say it was the sheer arrogance and attitude of the “AGW believers” that eventually turned me toward doing my own research. Mr. Bloom’s comments and Mr. Nuccitelli’s attacks are perfect examples of such behavior.

Most of the BBC lot like Roger Harrabin, Richard Black and David Shuckman are NOT scientists

How can the BBC use hacks who cannot understand the data they have to read?

Susan Watts is the only one worth listening to.

No one dies climate change, it’s a BBC spin line. What many people (including myself) are sceptical of is the data, the computer modelling and the arrogance of the so called climate change scientists who think they can predict the climate in 100 years time when the idiots can’t even predict it for next week. The BBC in particular have a habit of getting some climate change report and exaggerating the TOP END PREDICTIONS whilst playing down the ‘might’ ‘perhaps’ or ‘maybe’ phrases used in these reports based on predictions and models.

Yes the climate is changing and yes humans are probably contributing to that change, but so what?

We can’t undo our technology and we can’t deny those in the 3rd world the right to electricity, cars or a decent life.

It’s much easier for humans to simply adapt to the changes.

Michael W

Sorry my friend, but the (global mean) temperature is what has been used to promote the scare. If you want invoke ‘natural variability’ to make excuses for why it now doesn’t seem to want to play along anymore, you should included them the whole time. Definitely not claimed that they ‘cannot explain what we are seeing presently’.

Anyway Foster and Rahmstorf is just a curve-fitting excercise. It is definitely no knowledge, and not referring to it is most definitely not ‘out of context’ or misleading.

But it’s funny: Now you claim that the raw data, the one they’ve been fighting so fiercely about, and whose adjustments and ‘homogenization’ are so vehemently guarded secrets, and so carefully ‘enhanced’ products … that they have no meaning. That’s quite at step forward I would say.

And how would you know that what we’ve seen for some 1½ decade is only weather? And that it wasn’t before? Are you just sharing your beliefs with us? Because that’s OK. But be prepared that people will not share yours on just you saying ‘it is so’.

Also funny is the pretense indignation over things being said on air by non-scientists. Where have these guys been dwelling since TV came about? Or newspapers?

Surely much of the educated-guessing around the pause is based on the idea that natural processes do intervene to change the rate temperature change (not sarc). But that is clearly only for cooling (sarc).

1.) “we don’t just use the real data”

2.) “there is a lot of adjustments that have to be done”

Simply said, that is why we are here and have a mess on our hands.

Michael

It’s ver simple: There has been a pause, or hiatus. And it is not what has been predicted or expected. If you claim otherwise, you are at odds even with the scientists on your own side (whatever that is).

And no, you don’t get to change your metrics arbitrarily, you don’t even get to include more ad hoc hypotheses to reframe your narrative.

If you you need to do that, you tacitly agree that what you believed before was not right or at least not sufficient. As many have told you long before, and you’ve dismissed!

Jonas, care, we are being sucked into the warmist definitions. Until/if the warming continues then it can be called a “pause”. Currently we know it has stopped and that is all. Certainly the warmists know no different despite their floundering around with it being drowned in the oceans or the models predicted this anyway but they forgot to tell us.

Any notion of scientific consensus, is necessarily complex and involves a broad array of points of contention with several positions possible for each. Simplification of measurement of this putative ‘consensus’ is necessary in order to make the project of measuring it possible on practical grounds. Such simplification however renders survey results to be reflective of the methodology and its flaws rather than the underlying data.

But Michael, what happens if the public are smarter than you think and see through the shallow and unconvincing false dichotomy that underpins your comparison?

Also: to Mike Hulme, thanks for adding your voice to the criticism of this very poor piece of “scientific” research.

Ah, now here we come to the point.

You see, I don’t have to convince you of anything. I’m just a simple member of the public, who is quite suspicious of people who try to force others to believe in AGW with a mish-mash of technical jargon on irrelevant issues. If you want to try to push this scam, it’s YOUR job to convince ME that there really is a problem here, and that cutting human CO2 output is a practical way of sorting it.

And so far you are failing at the first post, by blatantly trying to switch the discussion away from the ‘even temperatures’ issue, which was the point at question. Very much the sort of thing a salesman or a politician does. Which, of course, is what is being seen with AGW across the country. The activists supporting this debunked theory are treating every public interaction as some kind of car they must sell, or political debate which they have to win by any means, while most normal people are simply interested in finding out the truth, and are well aware that they aren’t going to get it from people who treat all non-believers as the opposition…

I focused on the point where you told me I had said the opposite of what I actually said. Of course that wan’t your only error. You only get evidence filtered through the likes of WUWT and BH, so there is much you’re wrong about. I’d suggest again that you try looking at source material, but as you say all of this is, for you, a matter of belief.

But sure, re those “even temperatures,” you said: “The Earth has maintained the same temperatures, within a few degrees, for virtually all of its existence.” Well, that’s wrong, too, isn’t it, unless by a “few” you mean on the order of 10C (and that’s just GMST – regionally it gets much more extreme)? See here. Note that it’s ~13C from peak Eocene (conditions that we are now risking a repeat of) to the lows of the recent glacials.

Now, is there anything else I’ve ignored that you really need an answer to?

Just one minor point Steve… Real scientists work in Kelvin, a variation of about 10 of which indicates stability of the order of +/- 2%. Pretty good for a natural process.

Yes, a fact to which we owe our continued presence (although “real scientists work in Kelvin” is a very dull thing to have said). A repeat of the Eocene heat would by no means kill us off, although the stress might cause us to do it to ourselves by other means.

C20th SST warming 0.8K/273K=0.3%

Solar TSI variation over a single cycle = 0.1%

Solar TSI variation over C20th 0.1% +/- 0.05%

Possible amplification of solar signal by cloud cover changes calculated by using the oceans as a calorimeter (Prof. Nir Shaviv Journal Geophys research) – 3-7 times.

Conclusion:

It is possible that solar variation in concert with cloud cover change is responsible for between nearly all to around half of the C20th warming.

Evidence supporting a larger rather than smaller solar contribution:

Berrylium 10 isotope records indicative of solar variation match quite well with various paleo proxy indicators of temperature variation.

It might be a “very dull thing to have said” but as an old-fashioned (and retired) physicist I prefer to use units that are in step with the realities of the universe rather than those of an arbitrary scale derived from the freezing and boiling points of water. I realise that 10 degrees on a scale of 100 represents 10% and thus looks more alarming (in which case why not go all left-pondian and use Fahrenheit as it’d then be 18 degrees!).

Aha, I had been about to accuse you of being a retired physicist and then I thought to myself how unfair it would be to say so. 🙂

Rog, if you have absolutely no filter for poor research results you are going to end up repeating a lot of it just because you’d like to think it was true. It results in you having no credibility even with those who mostly agree with you (e.g. Willis E.).

“…you said: “The Earth has maintained the same temperatures, within a few degrees, for virtually all of its existence.” Well, that’s wrong, too, isn’t it, unless by a “few” you mean on the order of 10C …”

Exactly. You were so anxious to state that I was wrong that you didn’t bother to think about what I was saying, and just responded with a general-purpose rebuttal.

It may also have escaped your attention that this thread is not about the science of Global Warming – it’s about public perceptions. As I said, I’m a simple member of the public, so in a sense I am the customer here, and you are the salesman.

And what a bad job you are making of it! To start with, ‘knocking’ your competitors (if that is how you see WHWT and BH) is NEVER a good idea. Listening to your customer’s requirements would help. Leading the sales pitch away from his concerns over to what you want to talk about makes him suspicious of your intentions. Talking down to him, telling him all his beliefs are wrong before you have even found out what they are and implying that you have all the correct answers in a field which we now all know is tentative makes you sound like one of those ever-more-desperate solar panel salesmen…

Sorry, but I don’t think I’ll buy my double-glazing, my next car or my climate beliefs from you. Looking at the way you have gone about things, would you?

I’d say nice attempt at dodging, but it wasn’t especially. FYI at peak Eocene temps the tropics become largely uninhabitable for humans.

In terms of convincing you, I have no hopes. Serial sharp effects personally experienced might do it. but I’m not even sure that’s true given how hard it is to let go of lifelong preconceptions. Much more likely is that, per Planck’s dictum (what did he know, right?), a significant chunk of your generation will have to die off before the necessary critical social mass can be achieved. Unfortunately, by then it will probably be too late to avoid a lot of the really nasty stuff.

And no, not competitors at all.

Mike Hulme

Your brief comment here was remarked by Andrew Montford on his blog at

http://bishophill.squarespace.com/blog/2013/7/25/hulme-slams-97-paper.html

and has provoked a long discussion there, much of it critical, though you have been admirably defended by Ben Pile, whom you describe as “spot on” in this article.

You say that “it is a sign of the desperately poor level of public and policy debate in this country” that the energy minister should cite the Cook/Nuccitelli 97% claim.

We sceptics commenting here and at BishopHill agree with you, and like to think we are trying to raise the level of debate, but can do little to get our voices heard outside the blogosphere. I’m sure you’d agree that Ben Pile’s thoughtful criticisms deserve to be aired in a more influential forum – Times Higher Education or The Conversation would seem to be appropriate – or even Guardian Environment, where Nuccitelli is a regular contributor.

We can’t do that, but you can. Any editor would see the significance of a criticism of the 97% consensus coming from you, and would offer you a platform to expand on your comments here. It would be a golden opportunity for you to do somethng about the “desperately poor level of public and policy debate in this country”. I hope you seize it.

Mike has his own credibility to worry about, although if he wants to spend it on this, by all means.

Prof Mike Hulme’s credibility vs Dana Nuccitelli’s ? – no contest – Mike is far more eloquent and reasoned and open to discussion

Hi everybody, as Warren is on holiday, I’ll be moderating the comments for a while. Only those who post a blog post get automatic alerts about incoming comments. This means that for this post I won’t get alerted of incoming comments automatically. However, I’ll check for comments as regularly as possible. There may be some delays though in the moderation process.

Maybe someone could explain something to me. Firstly the “97% concensus” claim. Apart from the issue that it seems to be argumentum ad populum which is “The basic idea is that a claim is accepted as being true simply because most people are favorably inclined towards the claim. More formally, the fact that most people have favorable emotions associated with the claim is substituted in place of actual evidence for the claim. A person falls prey to this fallacy if he accepts a claim as being true simply because most other people approve of the claim”,there is never such a thing in science. There’s always more to learn,and secondly how on earth would you go about proving such a thing,as believing that there is “consensus” based on the word of a few people,how do we know that they aren’t telling lies in stating this?

Michael Patterson:

As I said in a comment at

http://bishophill.squarespace.com/blog/2013/7/25/hulme-slams-97-paper.html

the Cook/ Nuccitelli paper is not any old poorly devised social science paper. It is truly unique in that (though Cook won’t release all the data) the relevant discussions which led up to the formulation of the research are in the public domain (see Barry Woods’ comments at the top of this thread). We therefore know that Cook, Nuccitelli etc decided the results they wanted, devised research to produce those results, and even planned how to market the results in a publicity campaign, before they even started the research.

If you’re new to the world of global warming propaganda, you need to know that Cook and Nuccitelli are leading authors on a blog called SkepticalScience whose aim is to counter scepticism of “orthodox” climate science. In March last year they accidentally made available their internal e-mail correspondence, revealing how they go about what is essentially a large scale propaganda campaign. Cook, who has no relevant qualifications, has since obtained a university appointment and even a temprorary professorship, and was a joint author of a paper “Recursive Fury” which accused a large number of named climate sceptics of being “conspiracy ideationists”. (The paper has been removed from the journal website pending enquiries provoked by complaints).

Nuccitelli is coproprietor of an organisation called “Climate Consensus – the 97%”, which is part of the Guardian Environment Network. He has had eighteen articles published on the online edition of the Guardian in the past three months, while helping to run the SkepticalScience blog and holding a fulltime job in a company involved in oil exploration.

While not directly answering your question, I hope it helps.

@ Paul

“Peter, your view… is completely wrong.”

This should be interesting.

“see also this post from Science communication expert Dan Kahan, where he is very cynical about the idea that declaring a scientific consensus will convince the public.”

Thanks, Paul, but I am familiar both with Kahan’s initial, incorrect, and embarrassing reaction (which you link to), as well as his mea culpa in which he expresses contrition over his knee jerk dismissal of the paper a few days later.

And while Kahan’s later comments were certainly less irresponsible than his initial reaction, he still utterly fails to grapple with the body of evidence that indeed shows communicating the consensus actually impacts public belief- not only about the science itself, but also in willingness to support action. Kahan, Professor Hulme, and yourself could probably benefit from actually looking at what this evidence shows rather than simply parroting the line that communicating the consensus doesn’t matter. See points 2 and 3 here: http://www.culturalcognition.net/john-cook-on-communicating-con/

If you have any questions about this evidence, please feel free to contact me.

“Kahan links to Keith Kloor, who in turn links to David Appell, all saying much the same thing.”