March 14, 2025, by Brigitte Nerlich

Fin-de-Siècle Youth Magazines and their Construction of Gendered Responses to Sickness

This is a post by SUSAN SUDBURY. Susan is a fifth-year honours student completing a Bachelor of Advanced Humanities at the University of Queensland, Australia, where she is studying an extended major in English Literature. I am here reposting with permission a blog post that she wrote as part of the Media and Epidemics project.

Susan joined the UK Media and Epidemics team under the supervision of PI Melissa Dickson as a recipient of a 2025 Summer Research Scholarship from the University of Queensland, Australia. The Summer Research team is focusing on the Influenza Epidemic in England which began in 1889 and studying the cultural and social impact this colloquially dubbed ‘Russian Flu’ had on the following two decades.

***

Is there such a thing as a ‘correct’ response to news about deadly viruses affecting one’s community, city, or nation? The contemporary social norms that affect behaviour are important factors in understanding how epidemics are perceived, whether it be five years ago or a hundred and thirty-six.

Modern-day readers have now experienced living through a pandemic in some shape or form. I was in my final year of high school when news of COVID-19 began to circulate, and I still remember the medley reactions from fellow students. Some were stressed, with a distinctly bitter flavour of “Why us; why now?” coating their anxiety about whether graduation celebrations were to be cancelled. Some were more concerned about their grades; others about their impending physical seclusion from their friends; others about the health of themselves and their families. Then there were the ones reporting the latest news from the back of the class, only looking up from their phones to mutter “We’re all doomed” with a ragged smirk that slowly glazed over as their thumbs continued to scroll.

The need to know the next new strain, the differing symptoms, and the increasing number of cases was paramount. Perhaps for some it was because of the spectacle, but for most it was the strong sentiment that remained underneath all other worries and was symbolised in the visible increase of hand sanitiser bottles hanging in the outer pockets of backpacks: nobody wanted to get sick.

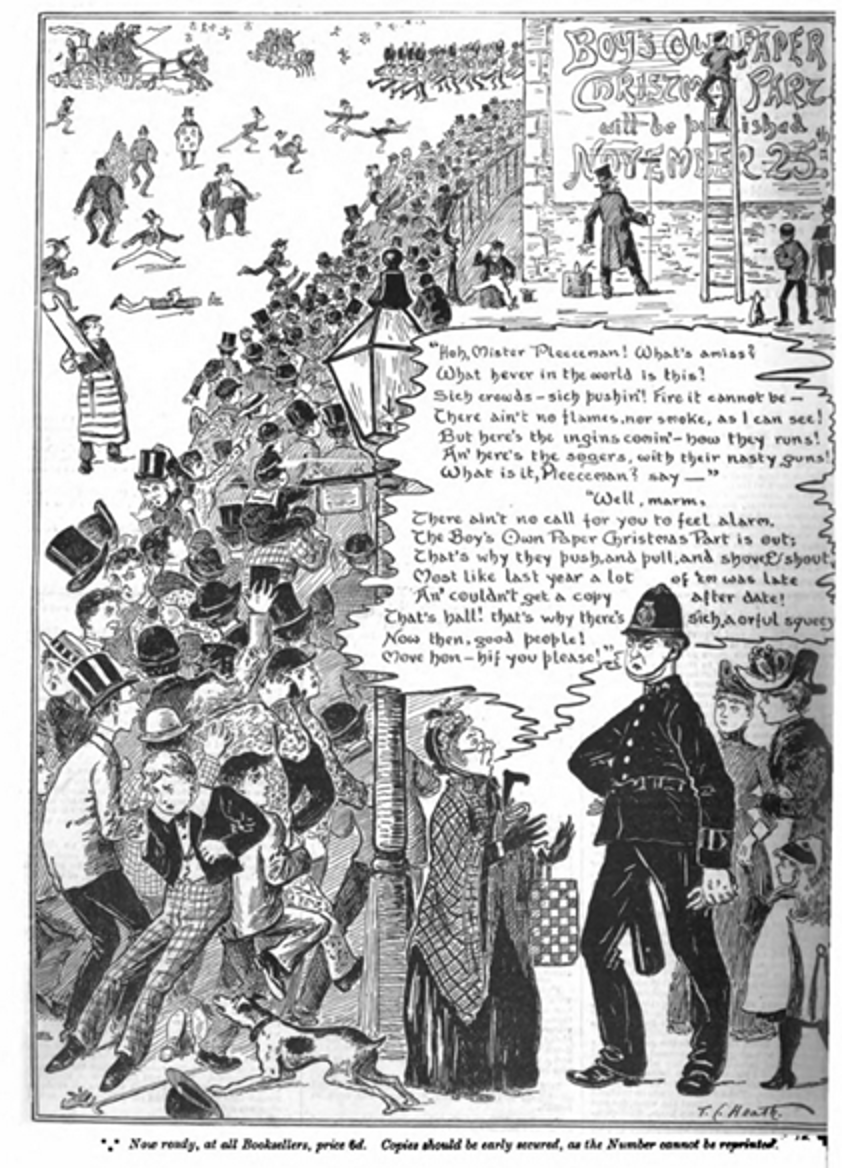

With smart phones in every student’s pocket, our access to information was consistent and readily available. By comparison, for young people in Britain during the Influenza Epidemic which began in 1889, the proliferation of mass-produced magazines in the fin de siècle increased the opportunity for all to cheaply obtain regular news. An analysis of The Boy’s Own Papers and The Girl’s Own Papers (B.O.P. and G.O.P.) from October 1889–September 1898, as magazines with a youth focus, are therefore important primary sources to study as a way to understand the content young people were consuming during the epidemic and how they were responding to it. This latter aspect can be found in the Correspondence sections of these magazines, which offer insight into the main anxieties plaguing young people, many of whom were concerned about their health. Much like my own peers during our encounter with COVID-19, it is clear that no one wanted to get sick. Figure 1. A promotional page from the November 30, 1889 edition of The Boy’s Own Paper, depicting a sprawling queue of readers wishing to purchase that year’s limited Christmas Number. Source: Internet Archive.

Figure 1. A promotional page from the November 30, 1889 edition of The Boy’s Own Paper, depicting a sprawling queue of readers wishing to purchase that year’s limited Christmas Number. Source: Internet Archive.

However, whether the content of these magazines is truly reflective of public sentiment regarding the colloquially dubbed ‘Russian Flu’ epidemic is an issue which can be called into question. Responses to sickness within both magazines are placed into a rigid gendered dichotomy. These messages to young people about supposed ‘correct’ health responses offer insight into how people were expected to react to mass health events in fin-de-siècle Britain.

Make a Man of You

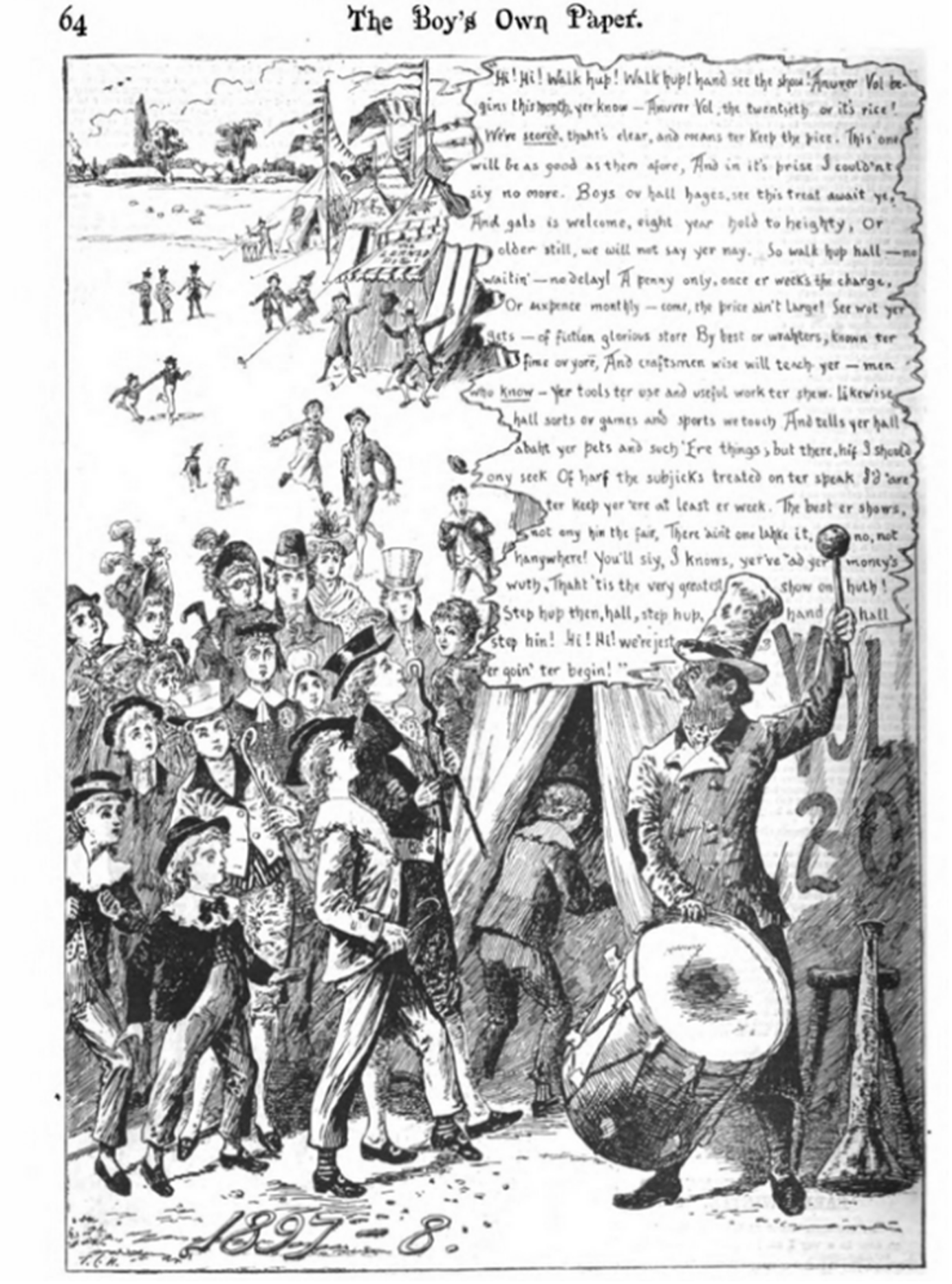

The publications of these two different magazines, one for ‘boys’ and one for ‘girls’, is indicative of an attempt to construct two distinct gendered characters, both coded as white, middle-class, and preferably British. Of course, the magazines recognise that their readership is not from one demographic, as seen in B.O.P. promotional pages, where “Boys ov hall hages, see this treat await ye, And gals is welcome, eight year hold to heighty, Or older still, we will not say yer nay” (see Figure 2).1 Yet this acknowledgement does not diminish the fact that normative gendered roles are prescribed in the fiction and non-fictional articles in both Papers. As Dr. Gordon Stables describes as the purpose of his columns in the B.O.P., dwelling on “matters that tend to make men of boys, and keep the hearts of boys in men” is also the general constitution of the magazine over all.2

Figure 2: Promotional page from November 23, 1897, for The Boy’s Own Paper. Source: Internet Archive.

Advice on health is also subject to gendered variations, as seen in Stables’ construction of “The Boy-Gentleman”. In this article he evokes “the good old proverb, ‘Cleanliness is next to godliness’”, which Stables explains can be achieved through “Early rising, a sufficient amount of pleasure-giving exercise in the open air, eating slowly, bathing regularly, temperance in everything, and the most complete chastity in thoughts and actions”.3 It is these that constitute the “general laws of health or golden rules of hygiene” which are so frequently recommended to readers worried about their health.4 It is precisely these “rules of health as laid down plainly by Dr. Gordon Stables” that the B.O.P. editors recommend to a “troubled one” asking, “Will life be worth living?”.5 This young reader is like the frequently scorned ‘weakly’ boys Stables describes that lie “in bed for ten minutes thinking yourself the most unhappy boy in Christendom because you have to get up at all” instead of springing out of bed “like a man” to have a morning bath.6 It will “positively increase your stature”, Stables says, again suggesting that to adhere to these principles is to progress from a boy to a man.7

Despite being socially required to obey the laws of hygiene, boys and men made sure that they were not overly concerned with it, else they risked being described as nervous or weakly. This can be seen in David Ker’s serial, “Captives of the Ocean”, where sick tourists are ridiculed for supposedly dithering about their health to an extent that constitutes an emasculation.8 ‘Those men are not like us’, Ker’s Cameron seems to imply, not like us real men that come back from expeditions to the Congo or the Americas, not with ailments, but with “a souvenir of my sojourn”, as Dr. Arthur Stradling describes his own malarial fever.9

Figure 3: An example of a front page of The Boy’s Own Paper, where mortal dangers are much more graspable, like a python about to eat you, than the invisible microscopic threats of bacteria. Source: Internet Archive.

The magazine’s definition of their masculine type as one unconcerned about all physical threats, and uncomplaining about any ailments if affected, can perhaps explain why there are few mentions of influenza in the B.O.P., especially in the early epidemic years. It is only later, in 1898, when the ubiquitous Dr. Stables falls ill with the virus, that it is spoken about with any gravity. Apart from his columns, young boys would have found next to no other mentions regarding the flu anywhere else in the magazine that is supposed to engender their development as individuals. If young people wanted to get popular health advice, The Girl’s Own Paper was much more informative.

A Woman’s Sphere of Work

The apathy towards treating sickness which is seen in the B.O.P. is nowhere to be found in the G.O.P., where there is abundant anxiety about contracting disease and caring for the sick. In fact, this difference between these two gendered responses can be found in Alice MacDonald’s serial, “A Chameleon”, where news of influenza in the heroine’s extended family gives her cause for concern since she knows that “people die from influenza”.10 The response of Wendall, her love interest, however, is flippant: “Oh, it’s only influenza”.11 Wendall’s unspoken shrug of the shoulders is perhaps indicative of wider sentiment during the initial period of the epidemic, because like in the B.O.P., there are few mentions of an influenza epidemic.

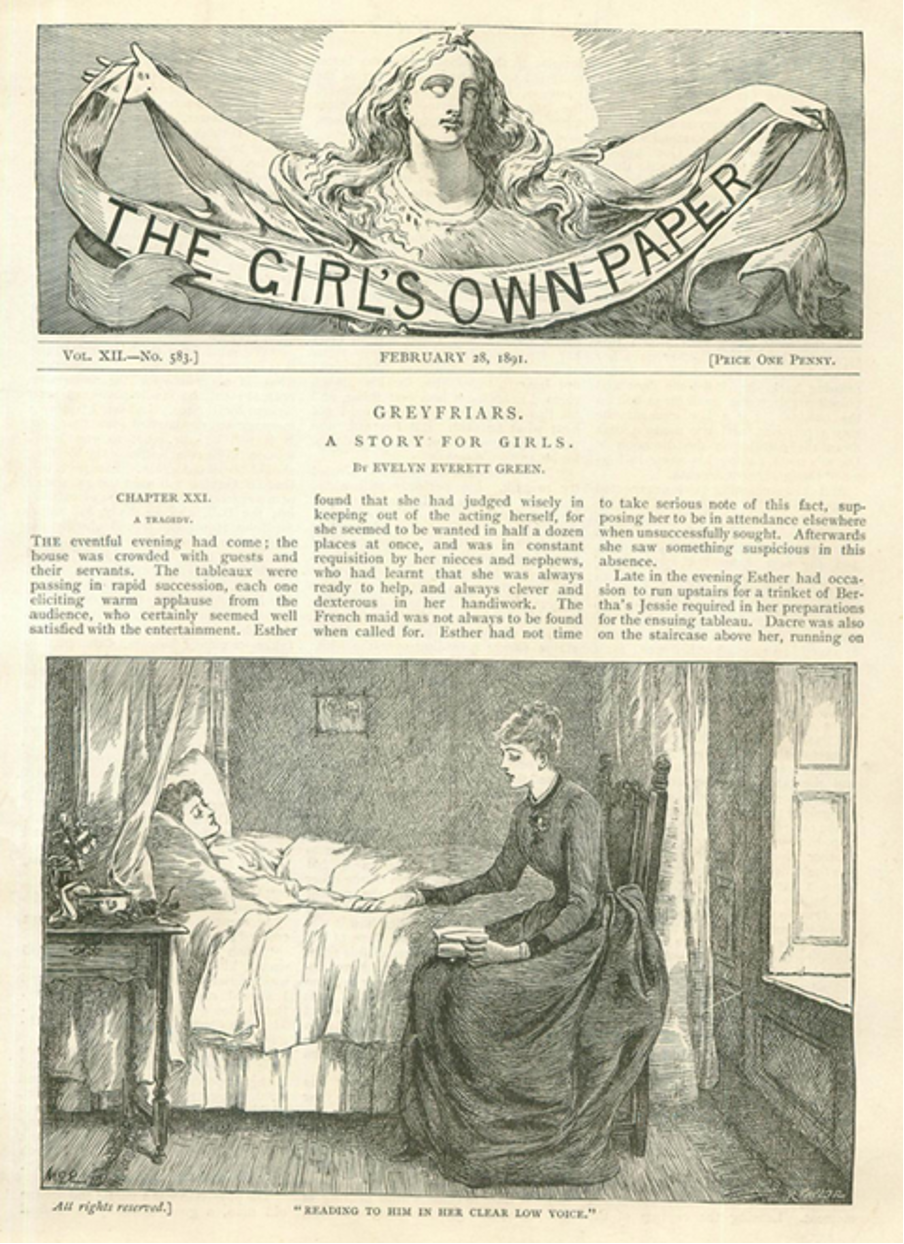

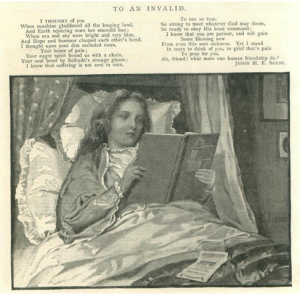

It is only later, as seen in Lily Watson’s 1896 serial, “A Child of Genius”, that influenza is depicted as having a disruptive impact. This disruption is prompted by the incapacitation of the heroine’s mother who, as both “nurse-in-chief and cook-in-chief”, leaves the household suffering “from the lack of her…services”.12 The impact of influenza and other illnesses on domestic life offer a reason why health is so absent from the B.O.P. where the adventure romance reigns supreme, compared to the G.O.P. which is a prolific publisher of domestic realism. For young women reading “A Child of Genius”, the message to them is to take initiative to use their “energies…to work to alter the face of things” when faced with ill family members.13 As illustrated in this blog post’s opening image, sickness thus offers an opportunity for girls to show responsibility by caring for others, thereby illustrating a path to personal development into womanhood.

This is part of a wider movement to encourage women to become the “health-officers of the world”.14 It is argued in the G.O.P. that “ladies are those who can do this best” because women are the ones “who live in our houses in which the menkind often are but visitors; they are the ones who manage the children, and the servants, and the housekeeping, and the schooling, the man being in all things the paymaster”.15 With their “quickness, shrewdness, patience, ingenuity, sympathy, and intelligence”, women are painted as motherly protectors of the sick and teachers of the rules of hygiene.16

Comparing this messaging to the health advice for boys, which is centred on the individual and personally motivated, the role of women is fashioned as a communal, public duty which must be spread, as A. T. Schofield suggests, “throughout England almost as rapidly as the influenza”.17 This splitting of health advice down gendered lines, although creating prejudices, is also indicative of an attempt to promote an organised response to epidemics.

Figure 4: Poem by Jessie M. E. Saxby titled “To an Invalid”, published 3 October 1896, accompanied with an image depicting a young girl sat up in bed reading The Girl’s Own Annual. Source: Internet Archive.

You Are But One of Many

The B.O.P. and G.O.P. are examples of how, like during the COVID-19 pandemic, very different attitudes towards health and disease can be found depending on differing sources. There seemed to be a unified response being cultivated in the G.O.P.; the B.O.P. was business-as-usual. Understanding the kinds of content young people were consuming during and after the initial epidemic enables us to understand how socially prescribed expectations and public perceptions are affected by mass health events.

It is of course hard to know exactly how young people were feeling at the time of the Russian Flu. Yet the Correspondence sections of both magazines were never lacking in questions regarding health. Indeed, the children reading these Papers are doubtless not as carefree about their health as might be supposed by the indifference seen in magazines like the B.O.P. itself. As the editor of the B.O.P. acknowledged in his response to the young boy asking if life is worth all the hassle, “you are but one of many ‘troubled ones’, therefore we will answer you”.18

Footnotes

The Boy’s Own Paper, vol. 20, no. 980, 23 November 1897, p. 64. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/the-boys-own-annual-the-boys-own-paper-20/page/64/mode/1up?view=theater. Accessed 2 March 2025. ↩︎

Stables, Gordon. “Recreation: From a Health Point of View.” The Boy’s Own Paper, vol. 15, no. 722, 12 November 1892, pp.106-7. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/the-boys-own-annual-the-boys-own-paper-15.1892-93/page/106/mode/1up?view=theater. Accessed 2 March 2025. ↩︎

Stables, Gordon. “The Boy-Gentleman.” The Boy’s Own Paper, vol. 12, no. 571, 21 December 1889, p. 187. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/the-boys-own-annual-the-boys-own-paper-12.1889-90/page/187/mode/1up?view=theater. Accessed 2 March 2025. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

“Correspondence.” The Boy’s Own Paper, vol.12, no. 570, 14 December 1889, p. 176. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/the-boys-own-annual-the-boys-own-paper-12.1889-90/page/176/mode/1up?view=theater. Accessed 2 March 2025. ↩︎

Stables, “The Boy-Gentleman,” p. 187. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Ker, David. “Captives of the Ocean: A Story of the Canary Islands.” The Boy’s Own Paper, vol. 16, no. 774, 11 November 1893, pp.89-92. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/the-boys-own-annual-the-boys-own-paper-16/page/90/mode/1up?view=theater. Accessed 2 March 2025. ↩︎

Stradling, Arthur. “Alligators and Crocodiles.” The Boy’s Own Paper, vol. 12, no. 560, 5 October 1889, pp. 4-5. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/the-boys-own-annual-the-boys-own-paper-12.1889-90/page/5/mode/1up?view=theater. Accessed 2 March 2025. ↩︎

MacDonald, Alice. “A Chameleon.” The Girl’s Own Paper, vol. 13, no. 630, 23 January 1892, p. 267. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/gop-1892/page/267/mode/1up?view=theater. Accessed 2 March 2025. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Watson, Lily. “A Child of Genius.” The Girl’s Own Paper, vol. 17, no. 873, 19 September 1896, pp. 811-12. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/gop-1896/page/812/mode/1up?view=theater. Accessed 2 March 2025. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

“The Missed Mission.” The Girl’s Own Paper, vol. 16, no. 781, 15 December 1894, pp. 172-73. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/gop-1895/page/172/mode/1up?view=theater. Accessed 2 March 2025. ↩︎

Schofield, A. T. “A New Career for Ladies.” The Girl’s Own Paper, vol. 12, no. 612, 19 September 1891, pp. 809-10. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/gop-1891/page/809/mode/1up?view=theater. Accessed 2 March 2025. AND “The Missed Mission,” p. 172. ↩︎

“The Missed Mission,” p. 173. ↩︎

Schofield, “A New Career for Ladies,” p. 810. ↩︎

“Correspondence,” The Boy’s Own Paper, p.176. ↩︎

Feature image:

An example of a front page of The Girl’s Own Paper. A young woman is illustrated as reading to a young man lying ill in bed, emphasising women’s role as caregiver. Source: Internet Archive

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply