April 11, 2025, by Brigitte Nerlich

Science, stories and the secrets of survival

I recently read a post on Bluesky by Adam Roberts, a British science fiction and fantasy novelist that said: “MODERN MAGIC MAKES MANIFEST MERLIN’S MEDIEVAL MYSTERIES”. I was instantly hooked and found out that this is a nicely alliterative rendition of the original title of a press release announcing that “Fragments of a rare Merlin manuscript from c. 1300 have been discovered and digitised in a ground-breaking three-year project at Cambridge University Library”. That’s the sort of scientific discovery that nobody can object to, I thought. What is it about?

In 2019 experts working at Cambridge University Library discovered that the binding or cover of a 16th-century archival register was made from an old manuscript. But how could one get access to it and read it without damaging it and the register?

In the following I’ll first summarise the story of the discovery and decipherment of the mystery manuscript, then say something about the arts and sciences involved in this endeavour and then ask the question: What’s the value of these arts and sciences and what if we had never funded them in the past and what if we no longer fund them in the future?

Discovery

Let’s start at the beginning. The significance of the 2019 find was recognised by Dr Irène Fabry-Tehranchi a member of Cambridge University Library staff in charge of the French collections.

As it turns out, she did her thesis at Paris 3, Sorbonne Nouvelle in 2011 on….: “Texte et image des manuscrits du Merlin en prose et de la Suite Vulgate, mise en cycle et poétique de la continuation ou suite et fin d’un Roman de Merlin?” (“Text and image of the manuscripts of Merlin in prose and the Vulgate Suite, cycle and poetics of the continuation or sequel and end of a Romance of Merlin”) That was a good preparation for recognising a strange book binding as …. “part of the Suite Vulgate du Merlin, a French-language sequel to the legend of King Arthur”, which was identified as having been written between 1275 and 1315.

Arthur and Merlin

We have all heard stories about King Arthur and Merlin. But what story does the manuscript tell? To understand that, we must step back a bit first. There is something called the Lancelot-Grail cycle (and, again, we all have some vague memories of Sir Lancelot and/or the Holy Grail). This cycle, or group of interconnected stories, has five parts (and I am simplifying). The second part is called ‘The Merlin’ or ‘Prose Merlin’ and recounts the life of Merlin and his efforts to promote the cause of Uther Pendragon, Arthur’s father, Arthur becoming king and his coronation. The ‘Vulgate Suite de Merlin’, is the sequel to this and describes Arthur’s court after his coronation.

As Irène Fabry-Tehranchi explains: “The Suite Vulgate du Merlin tells us about Arthur’s early reign, his relationship with the knights of the Round Table and his heroic fight with the Saxons…It really shows Arthur in a positive light. He’s this young hero who marries Guinevere, invents the Round Table and has a good relationship with Merlin, his advisor.”

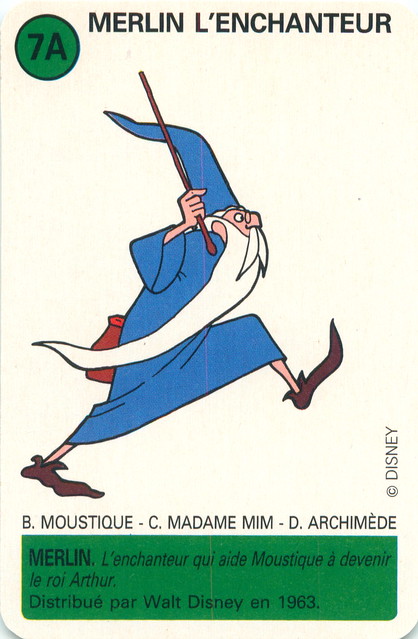

The stories of King Arthur and Merlin are part of our culture, including popular culture. When we hear about Merlin, we think of figures like the one I chose as the featured image, but when you read the manuscript that picture goes out of the window: “While they were rejoicing in the feast, and Kay the seneschal brought the first dish to King Arthur and Queen Guinevere, there arrived the most handsome man ever seen in Christian lands. He was wearing a silk tunic girded by a silk harness woven with gold and precious stones which glittered with such brightness that it illuminated the whole room.” Intriguing!

Decipherment

Let’s now look a bit closer at how the researchers got at passages like this. After the discovery of the book-binding-manuscript, a team of experts came together to tease out the text and its meaning, funded by a grant from Cambridge Digital Humanities.

The team was composed of academics with various types of expertise, such as Amélie Deblauwe, who has a background in Egyptology, photography and electronic arts; Błażej Mikuła, a filmmaker, photographer and radio producer; Sally Kilby, a book and paper conservator, and Maciej Pawlikowski, Head of The Cultural Heritage Imaging Laboratory (CHIL) which is itself part of Cambridge Digital Humanities, and who has a background in ethnology, anthropology, digital photography and 3D scanning; and many others.

What scientific technologies and methods did all these conservators, curators and imaging specialists use to virtually unfold and digitise this mysterious text and unlock its mysteries? Let’s have a look. (Here you can witness the virtual unfolding!)

Science and technology

As noted in one of their web posts, the researchers used “cutting-edge imaging and analysis technologies (Multispectral Imaging and X-ray examination by computed tomography, or CT-Scan) as well as ingenious virtual manipulations” to digitise the text and to get “access to hidden textual parts”. “This complemented traditional methods for the study of manuscripts (ranging from codicology, palaeography and art history to linguistics and textual study)”.

So, we have nice mixture of imaging science and technology that lets us look at things we can’t see with our eyes and decoding arts that let us read what we finally see.

Imagining science is the “study of the science, computing, and engineering theories behind the technology that goes into creating images, the integration of this technology into imaging systems, and the application of those systems to gather information and solve scientific problems”. Think about X-rays, so indispensable in accidents and emergencies; CT-scans that use multiple X-ray images used to diagnose diseases; multispectral imaging that enables us to see beyond the visible spectrum, used in medical diagnostics but also in warfare; 3D modelling which helps us build better or more fun worlds, virtually and really.

Codicology and palaeography are the arts of deciphering old manuscripts, with codicology focusing on the details of a manuscript to discover its origins and provenance, while palaeography focuses more on the handwriting in books, rolls and scrolls and so on.

Together these arts and sciences worked their ‘magic’ on the Merlin manuscript mystery.

The meaning of life

What would happen if research into all these enterprises had not been funded? What will happen if the research into and the application of such arts and sciences is no longer funded?

If imaging was reduced or cut in medicine, our life expectancy would go down, as we could no longer diagnose illnesses in the sophisticated ways we have become used to. But that is not all. We live by the stories we tell each other, including magical stories about King Arthur and Merlin. We rejoice in finds like the Merlin manuscript and the stories they tell. Depriving people of stories and joy is a way of perhaps not directly reducing life expectancy but of diminishing the meaning of life and making life less worth living. Both life expectancy and the meaning of life depend on art and science all the way down. They unlock the secrets of our bodies, and they unlock secrets that intrigue our minds.

PS. I am very proud that my own old thesis from 1986 (La pragmatique: Tradition ou révolution dans la linguistique française?) is on a shelve somewhere at the Cambridge University Library. It will never lead to a beautiful find like the Merlin one, but still, it’s there …

Image By Mark Anderson, Flickr, trading card for Merlin from Walt Disney’s The Sword in the Stone, released in 1963 (CC BY 2.0)

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply