May 10, 2024, by Brigitte Nerlich

Milk, reservoirs and spillovers: Bird flu in cows

On 26 April my sister emailed me from the United States and said “I might have to go over to oat milk”. She was alarmed by reports that bits of bird flu virus had been found in pasteurised milk. She has not gone over to oat milk yet. It seems that there is almost no risk of catching bird flu from commercial milk, as the pasteurisation process inactivates the virus (raw milk is another matter). But this made me think yet again about bird flu.

Bird flu and other epidemics

Bird flu, or avian flu or avian influenza or, more precisely, Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) caused by the virus H5N1, has been around for decades, affecting wild birds and poultry. Then in 1997 something happened. Eighteen people in Hong Kong, who had had contact with chickens, were infected and six died. That set alarm bells ringing.

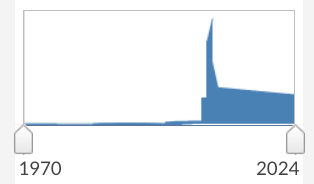

After that things went quiet for a bit. Then, in 2005, wild birds spread H5N1 to poultry in Africa, the Middle East and Europe. In Europe in particular, the public debate about bird flu became intense (see spike in reporting on this Nexis timeline), especially about the virus mutating to cause human to human spread and a new pandemic.

Figure: Nexis timeline for search on “bird flu” OR “avian flu” OR “avian influenza” OR H5N1

Fears were heightened as the beginning of the bird flu outbreak coincided with the 2003 outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome or SARS, caused by a coronavirus.

2009 saw the first major influenza pandemic of the 21st century, namely the swine flu pandemic that killed between 150,000 and 575,000 people. This was caused by the H1N1 virus.

Then things settled down again until 2019 and the advent of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 and Covid, which we all remember well.

In 2020 bird flu returned and has been killing millions of wild birds since October 2021 and infecting many other species, including mammals.

Then something surprising happened (good info here). In March 2024 the news started to spread that a new variant of the H5N1 virus known as 2.3.4.4b or A(H5N1) had spread to dairy cows in the United States and swept through herds all over the continent. (The outbreak is so far confined to the US)

The virus can now be transmitted between cows and also from cows to other animals, such as cats (more than half the cats on the first Texas dairy farm to test positive for H5N1 earlier this year died after drinking raw milk from infected cows).

Genomic analysis has established that “H5N1 is transmitting from cattle back into wild birds, poultry, cats, and other species”. There has also been a first spread from mammal to human, that is, to a dairy farm worker in direct contact with cattle. But more cases may be undetected.

On 24 April Americans were told that the milk they consumed may contain fragments of H5N1. That is quite alarming in various ways. Although there is, it seems, no danger to humans, this suggests that H5N1 is very widespread in US dairy cows. That is to say, there might now be a big virus reservoir in mammals, while before the reservoir was mainly in birds.

A ‘reservoir’ is an organism or environment where a virus typically lives and reproduces and a ‘spillover’ is the transmission of a virus from an animal to a human.

Quite a few ‘spill-over events’ of the avian virus into cows, cats, and even humans have been recorded and, as the New York Times said: “H5N1 is in a better position than ever to move between species and spill over aggressively into humans.” And as we have seen, there have also been ‘spillbacks’ from cows back to birds.

All these outbreaks happened in my and many other people’s life-time. There should be tons of things we can compare and contrast and learn from to deal with future epidemics and pandemics. In the following I just highlight a few things that came to mind. But I am not an epidemiologist….

Remember COVID?

At the beginning of the Covid pandemic there were intense speculations about how the SARS-CoV-2 virus was transmitted – through droplets, aerosols, touching contaminated surfaces etc. There was also a lot of uncertainty.

The same seems to be happening in the current H5N1 outbreak in cattle, where scientists are not quite sure yet what the most common transmission route is, especially between cows –milking equipment is a suspect, but so are droplets, cattle movements etc. The most important thing is to stay open to possibilities and be open about uncertainties.

As with Covid, there is some discussion about asymptomatic transmission. As Anjana Ahuja wrote in the Financial Times: “the presence of virus fragments in pasteurised milk points to the possibility of asymptomatic infected cows, meaning the virus could be spreading under the radar.”

Again, similar to Covid, there have been many discussions about testing and transparency, genomic sequencing and sharing of data. Only very recently was a Federal Order put out in the US to “mandate testing and reporting of cattle infected”. That is good, if rather slow. More surveillance would be better.

In the context of Covid, vaccines saved millions of lives. In the H5N1 case, a virus to which humans have no natural immunity, governments are preparing various kinds of vaccines. Moderna and AstraZeneca, names we know so well, are mentioned. These names come with some PR baggage though – something to think about.

And finally, in terms of occupational health, that is the health of farmworkers etc., it is important to remember your appropriate PPEs! Masks, eye protection, ventilation etc. etc.

Remember bird flu

What sticks in my mind from the 2005 outbreak is the huge amount of press coverage this ‘killer flu’ received and the alarming numbers that were bandied about, something that I haven’t seen yet in this outbreak.

Towards the end of 2005 the then Chief Medical Officer Liam Donaldson caused some panic, for example, when he announced several times that at least 50,000 people might die if a flu pandemic struck the UK.

In 2005 there was a lot of talk about stockpiling Tamiflu, the only anti-viral drug available, and we are talking about stockpiling Tamiflu again now, but in less urgent terms. In 2005 Professor John Oxford, an authority on bird flu, said: ”that Britain would need some 20 million courses. He said: ‘This is a national emergency’” (Independent, 27 February 2005, italics added).

At the time it was really difficult to find a balance between alerting and alarming people, something that is also being discussed now. As Helen Branswell, one of the best sources on the current bird flu outbreak said on Mastodon on 2 May 2024: “The challenging thing about communicating the risk of #flu pandemics is the risk is low — until it isn’t. Then things happen really quickly.”

Remember swine flu?

There is some worry about H5N1 potentially infecting pigs. It’s good to see that pigs are therefore routinely tested. So far tests have been negative.

As Anjana Ahuja points out in her Financial Times article: “One concern is ‘reassortment’: when two flu viruses circulating in the same infected animal swap genetic material.” And Kai Kupferschmidt reports in Science, there ‘is a fear that “cows, like pigs, could become influenza ‘mixing vessels’ that create dangerous new human strains when avian and mammalian flu viruses that simultaneously infect an animal exchange genes”.

Remember BSE?

Going back in time, to the end of the 1990s, there was BSE or mad cow disease, when we all wondered whether it was wise to eat beef. With viral fragments of H5N1 found in milk and people in the US also worrying about eating beef, it’s good to see that some thoughts are given to the important issue of risk communication, which failed during the BSE crisis.

The New York Times reported that the milk issue “has prompted significant concern in the White House over how to avoid raising undue alarm about the dairy supply, according to people familiar with internal deliberations who were not authorized to speak publicly.” And: “Brian Ronholm, director of food policy at Consumer Reports, an advocacy organization, said that it would be ‘very critical’ for officials to clearly communicate the findings and educate consumers about what they mean.”

Remember climate change

Climate change and rising temperature lead to the increased spread of so-called ‘zoonotic’ diseases, that is diseases caused by germs that spread between animals and people. Climate change also exposes more people to ‘vector-borne‘ diseases, that diseases carried by mosquitoes or ticks that feed on human blood. They spread with the warming climate.

With regard to bird flu, Zhang Wenqing, head of the WHO’s global influenza prevention program, told a press conference that climate change might have disturbed birds’ habitats and migratory routes which might affect the spread of the virus.

Remember One Health?

This brings us to the real issue. All the things we can learn from all the recent epidemics and pandemics should feed into something called a “One Health” approach to pandemic preparedness and management. One Health is “the concept that human, animal, environmental and ecosystem health are linked”.

Although the WHO says they are pursuing a One Health approach, we have to ask what is being done about reservoirs and spillovers. As Angela Rasmussen says: “H5N1 is mostly in birds, but it has repeatedly crossed into many different mammals. Cats, dogs, mink, goats, bears, cows, sea lions, seals. Humans. If we want fewer cases in humans, we need to stop spread in these other species. We’re not doing that.”

We also need to understand the broader agricultural, economic and social implications of the spread of H5N1 and the ways that farmers, farmworkers, industry and vets deal with bird flu outbreaks.

Image: Spilt milk on Flickr

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply