April 7, 2023, by Brigitte Nerlich

Gene editing, gene shears and other titbits from the history of genetic engineering

I was wondering what to write about. In past blogs, I have done quite a bit of ‘conceptual history’ about metaphors or phrases like ‘imaginaries’, ‘tipping points’, ‘deficit model’, ‘trickle down economics’ and even ‘gene surgery‘ and ‘gene drive’. I have also written a few posts about gene editing or genome editing. But, come to think of it, I haven’t delved into the conceptual history of gene editing. This might be because I knew Matthew Cobb was writing a book/has now written a book, The Genetic Age: Our Perilous Quest to Edit Life, about the whole thing; so why bother, I thought.

Just out of curiosity though, I rummaged in my usual old shoe-boxes, so to speak, namely the Oxford English Dictionary, Scopus, the database of academic articles, and Nexis, the data base of news items. That turned out more interesting than I thought. I did not root around in any actual archives, something that Matthew certainly did, and he came up with an earlier history of the concept than I would have been able to detect using my lazy methods. In the following I briefly summarise what he found out and then discuss some titbits from my search activities.

Gene editing and the genetic age

In his book, Matthew notes that in the early 1980s new metaphors began to appear in genetic engineering, including the ‘editing’ metaphor. “In 1981, Arthur Riggs and Keiichi Itakura wrote a review of their synthetic DNA method in which they spoke of ‘gene editing’” (see p. 7). This was in the context of recombinant DNA and production of synthetic insulin. He also notes that in 1988, with the advent of word processors, Stephen Hall talked about ‘cutting and pasting’ in a popular science book (see p. 167).

However, he points out that ‘gene editing’ as a concept/metaphor “never really caught on, probably because the changes that could be introduced at the time were coarse and uncontrolled, which did not fit with the precision of the editing metaphor.” (p. 224)

That changed after the turn of the millennium, when, for example meganucleases began to be used for gene editing and, in 2010, the phrase ‘genome editing’ was used in the title of a seminal article for the journal Nature (see p. 224), Gene editing acquired its modern meaning, further cemented by the discovery of CRISPR after 2012.

So what could I add to that, I thought? Perhaps some titbits here and there. So, I went back to my usual sources like a magpie to its hunting grounds.

Gene editing in the OED

To find out about the history of words and concepts, lots of people use the Oxford English Dictionary which has specialised in ferreting out etymologies since 1884. Let’s first see how it defines ‘gene editing’.

They say that in molecular biology the word ‘editing’ means: “The alteration of a gene or other nucleotide sequence, involving the insertion, deletion, or replacement of one or more nucleotides, either as a natural process or using artificial techniques.” They point out that “frequently a distinguishing word is used, as in gene editing, genome editing or RNA editing”.

The OED traced the first use of ‘editing’ in molecular biology to a Stanford PhD dissertation from 1968, where an L. M. Okun claimed that the “Consistency editing of this sort may occur under certain circumstances in the processing of heteroduplex molecules of bacteriophage lambda DNA introduced into E. coli cells.” Okey dokey….

Then we jump to 1990 and find the use of ‘editing’ with additional words. The phrase ‘RNA editing’ is used in the EMBO journal, before ‘gene editing’ finally appears in 1991 with relation to engineered foods in a speech at the US Department of Agriculture (they talk about ‘marker genes’ and ‘editing genes’ being used to modify plants). The modern use of gene editing is attested for 2011 and genome editing is illustrated with a quote from 2015. So, the OED jumps over the 1980s somehow. But let’s keep an eye on the 1990s, when gene editing seems to have been in the air.

Gene editing in Scopus and Nexis

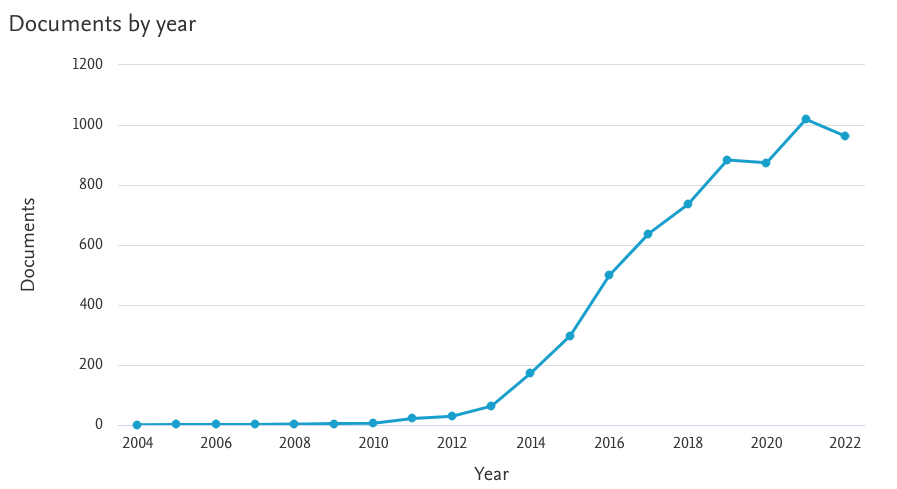

I first searched Scopus with the search terms ‘gene editing’ OR ‘genome editing’ and found the following timeline, with, it seemed, the first attestation for 1986 (in Cell). However, when I looked more closely at any of the early articles listed, I found that they talk about genes and editing but not gene editing. In the 1990s, as also found by the OED, there is some talk about RNA editing. I searched again but only in article titles. This time the first attestation for ‘gene editing’ is for 2004 which makes more sense. (Title: “Gene editing of a human gene in yeast artificial chromosomes using modified single-stranded DNA and dual targeting”)

“gene editing” OR “genome editing” in article titles (Scopus)

In any case, ‘gene editing’ began only to be used widely after 2012 when CRISPR became the editing tool par excellence.

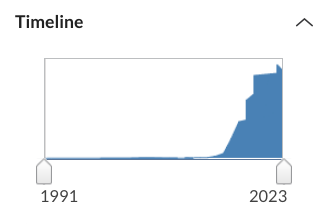

Now to Nexis. I used the same search terms and searched all English language news. The resulting timeline is not quite as smooth and, as unfortunately always with Nexis, not easy to read, but the steep rise of use starts again in around 2012.

“gene editing” OR “genome editing” in All English Language News (Nexis)

The first news item in the database that used the phrase ‘gene editing’ was from 1991. When I looked at it and a couple of other articles from the 1990s, things began to be a bit more interesting. I stumbled upon three variants of gene editing used in the 1980s and 1990s which I had not come across before, including one called ‘gene shears’. Let’s take a closer look.

Gene editing, gene shears and catalytic RNA

The first article I found was published in the Sydney Morning Herald on 20 March 1991 and hints at a patent tussle between the Australian government agency CSIRO (The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation) and Tom Cech from the University of Colorado over patents linked to a “revolutionary gene editing process”. The second article was also published in the Sydney Morning Herald on 20 March 1991 and shows that a priority for gene editing research at the time was to find ways to deal with the AIDS virus. What surprised me though was that CSIRO used a phrase that I had not encountered before, namely ‘gene shears’, perhaps not so surprising, as they were working in Australia.

The March Sydney Morning Herald article points out that: “The gene shears technology allows scientists to ‘switch off’ undesirable genes in plants and animals, and is expected to be used to improve varieties of plants and to control viral diseases. One of the priorities of researchers around the world is to try to disarm the AIDS virus with gene shear techniques.”

By digging a bit deeper on the internet, I found that the actual scientists at CSIRO involved in gene editing/gene shearing were Wayne Gerlach and Jim Haseloff. They worked on gene shears, a technology for splicing genes, around 1986 and published an article in Nature in 1988. However, this research later lost its funding and was, it seems, forgotten.

Tom Cech’s work, by contrast, flourished at the University of Colorado. He received the Nobel prize in Chemistry with Yale’s Sidney Altman for their discovery of the catalytic properties of RNA (ribonucleic acid) and realising that RNA can act like an enzyme.

The Sydney Morning Herald article from from 25 January 1991 pointed out that “Dr Cech…won the 1989 Nobel Prize for Chemistry for his discovery of how unwanted sections of genetic material can be edited out using certain ribozyme molecules. The ribozymes slice up similarly encoded molecules of messenger ribonucleic acid which transport genetic instructions to a cell’s protein factories.”

Jennifer Doudna, who, in 2020, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Emmanuelle Charpentier for work on gene editing, worked at Cech’s lab in the 1990s.

Gene editing and site-specific mutagenesis

The third article I found was published in The Vancouver Sun on 4 December 1993. Here I stumbled upon another Nobel Prize winner. This time it was Michael Smith who had won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in October 1993. The internet tells me that he had “collaborated with Clyde A. Hutchison to develop a new technique called ‘site-specific mutagenesis’, and was able to determine the effect of a single mutant gene. In 1978, Michael Smith used polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to successfully induce mutations at specific locations on DNA with certain primers. Therefore, in 1993, Smith and Kary Mullis, who invented the PCR technology, were awarded the 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.” PCR became briefly a household term during the coronavirus pandemic – we have probably all forgotten by now…

Back to the article in The Vancouver Sun. It was entitled, using a now well-established writing and editing metaphor: “Rewriting: The language of life” and provides an intriguing insight into the life of what the author calls “gene jockeys” but also “genetic editors”. The article also uses now well-known metaphors such as tinkering, stitching, cooking/recipe, deciphering, genes as words/sentences, writing, language, gene ‘shot guns’ etc. – I can’t quote all the passages here – I’ll just quote the passage on the scientists’ lives.

“When Michael Smith and the gene jockeys started tinkering with DNA more than 20 years ago, they were groping to understand the language of life. The thrill of discovery drove them on — often through nights and weekends — to isolate genes and decipher how they controlled every living thing on the planet. Families were ignored and marriages failed as the researchers pursued their passion for the genetic language. Smith proved, above all, a brilliant genetic editor.”

Smith (who, by the way, had been born to working class parents in Blackpool and worked with Fred Sanger at Cambridge) retired in 1998 but still nurtured younger talent, a fact celebrated in the next article, from The Ottawa Citizen, published on 29 July 1998.

The title of this article too echoes the emerging metaphors of the time: “Mapping humanity”… The article mentions his Nobel Prize (adding programming and tailoring into the metaphorical mix) “for his pioneering work on a method of reprogramming tiny segments of DNA, the substance in genes that provide instructions for the growth and development of any organism. The method allows scientists to alter genes, tailor new proteins and study existing ones.” Scientists rewrite, tinker, stitch and repair – even produce vaccines, but: “The problem is that genetic engineers have uncovered as many moral and safety questions as they have life forms.”

In the 1990s, the time when the Human Genome Programme began, we can see the advent of ‘gene editing’ but also the bedding in of a type of language in which ‘gene editing’ is embedded.

What have we learned?

The word ‘editing’ seems to have entered the language of molecular biology in around 1968 but lay fallow for around twenty years, until it began to be used together with ‘gene’ in the 1980s and 90s in Australia, the US and Canada in various contexts. Then it lay dormant again until hitting the headlines in around 2010. This post focused on the 1980s and 1990s.

In the early 1980s Arthur Riggs and Keiichi in the US Itakura talked about gene editing in their work on recombinant DNA and synthetic insulin, while Wayne Gerlach and Jim Haseloff in Australia used it in the context of ‘gene shears’ at the end of the 1980s. These two researchers were in a patenting, and ‘gene editing’, competition with an American researcher Tom Cech, but had to cede victory to him in the early 1990s.

Cech later received the Nobel for discovering that RNA can act like an enzyme and be used for gene editing. Around the same time the Canadian scientist, Michael Smith was awarded the Nobel for his work on site-specific mutagenesis and gene editing. Around the same time, the American Department of Agriculture started to talk about gene editing with relation to genetically modified food and distinguished between ‘marker genes’ and ‘editing genes’.

To understand this history of gene editing in more detail, especially the modern developments that I haven’t talked about, you have to read Matthew Cobb’s book!

But I also learned something from Matthew by corresponding with him. He pointed out to me that there seems to have been a shift in meaning from editing by the cell to editing by us, and that the two are seen as being completely different in scientists’ heads because of mechanism and function. It’s always good to talk to people who actually have a good grounding in science when it comes to understanding scientific metaphors and shifts in metaphorical meaning, in this case from ‘gene editing’ before and after around 2010.

Image: Wannapik Studio

Hi Brigitte!

I recently ordered the booklet: “[editing life] faces behind the gene editing revolution” produced by the French biopharmaceutical company Cellectis, which is intended to establish the priority of a number of its scientists (notably Edward Lanphier, Andre Choulika, George Church and others) for pioneering gene editing (if not the terminology), originally using zinc-finger nucleases, prior to CRISPR. I haven’t read Matthew Cobb’s book yet but look forward to end of academic term so I can do so.