July 15, 2022, by Brigitte Nerlich

Marianne North: On the trail of a Victorian painter and adventurer

A while ago, my husband listened, rather by chance, to Thought for the Day, where Rev Marie-Elsa Bragg mentioned a book called ‘A Vision of Eden’ by Marianne North (as an aside, North was an atheist). My husband later told me about the book, as he knew I was ’into such things’.

He also knew that I usually read a book of this kind on holiday (see picture) and a holiday was just around the corner. On previous holidays I had read some of my favourite books, such as The Philosophical Breakfast Club (about Whewell and his friends) This Thing of Darkness (about Darwin and FitzRoy), Dutch Light (about Huygens) The Invention of Nature (about Alexander von Humboldt) and more….. So this time I ordered A Vision of Eden and we took it with us – a rather heavy tome.

He also knew that I usually read a book of this kind on holiday (see picture) and a holiday was just around the corner. On previous holidays I had read some of my favourite books, such as The Philosophical Breakfast Club (about Whewell and his friends) This Thing of Darkness (about Darwin and FitzRoy), Dutch Light (about Huygens) The Invention of Nature (about Alexander von Humboldt) and more….. So this time I ordered A Vision of Eden and we took it with us – a rather heavy tome.

So what was it about the book that was ‘my’ thing? Let’s look at the person who wrote the book first, then at the book.

Travelling the world

Marianne North was an adventurer and botanical artist who lived in the middle to late 19th century (1830-1890), alongside such luminaries as Charles Darwin, who enticed her to travel to Australia and of whom she said that he was the “greatest living, most truthful, as well as the most unselfish and modest of men’, and William and Joseph Hooker, successive directors of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, who, by the end of the century, helped her establish a gallery at Kew wholly devoted to her paintings. Darwin was supposed to attend the opening of the gallery in 1882 but unfortunately died shortly beforehand.

By that time North had travelled all over the world painting plants, people and places wherever she went, on mountains, in deserts, in forests and in swamps. In Brazil, for example, she travelled in the footsteps of Alexander von Humboldt, like quite a few women traveller/artists at that time.

North had ‘learned’ to travel when roaming with her father all over Europe, but also Syria and Egypt (I’d love to see her paintings of that trip, but can’t find them). Unfortunately, her father died in 1869 when North was 40, and from then onwards, between 1871 and 1885, she travelled solo across six continents and seventeen countries, having never married (“Marianne thought marriage was a terrible idea, which turned women into ‘a sort of upper servant’”).

North was, one should stress, one of a number of Victorian women exploring the world at that time. Indeed, she visited one of them, Katherine Saunders, in South Africa. Saunders did not travel as extensively as North, but she was a fellow botanical artist and collector of plant specimens, some of which she sent to Kew Gardens.

Vision of Eden

After her travels, North wrote an autobiography, Recollections of a Happy Life, which was edited by her sister after her death and published in three volumes in 1892. ‘A Vision of Eden: The life and work of Marianne North’ is a shorter version of her memoirs published together with a selection of many of her most wonderful paintings, compiled and introduced by Anthony Huxley, another botanist and son of Julian Huxley and with a biographical note by Brenda E. Moon).

When reading the book, I got the impression that North was a really fearless woman. Of course, she was also rather privileged, being able to count on letters of recommendation to help and support her wherever she went – she was actually great at networking. But still, she seems to have been not only courageous and full of energy, but also of a rather happy go-lucky disposition and her writing shows that she had a great sense of humour. When visiting Egypt, for example, she reports “walking through an avenue of sphinxes who were apparently waiting for a surgeon to come to set their broken bones and the right heads on the right beasts” (Vision, p. 23)

Over time, travelling became perhaps something of an addiction, and not all was well towards the end of her rather short life, when she suffered from deafness and also delusions (Vision, p. 233).

Painting the world

The paintings chosen to illustrate the tales of her travels are eye-popping. Unlike many other botanical illustrators, North used oil, not watercolour, to create her paintings and said that oil painting became “a drug like dram-drinking, almost impossible to leave off once it gets possession of one.” (Huxley, Introduction, p. 13)

North’s paintings were colourful, “bold and bright”, quite unlike traditional botanical illustrations. Using oil “gave her paintings more vibrancy and impact. She also painted plants within their natural settings, sometimes including animals, temples and people in her paintings. Although different to traditional botanical illustration, it was a style that gave the viewer a sense of the habitats in which different plants grow.” She painted, as she put it herself, “plants in their homes” (Biographical note, Vision, p. 234)

As Huxley points out in his introduction: “In his Preface to the original catalogue Sir Joseph Hooker wrote […] of how many of the habitats ‘are already disappearing or are doomed shortly to disappear before the axe and the forest fires, the plough and the flock, of the ever advancing settler and colonist’.” (Vision, p. 13) He and North would weep at the destruction of the natural world that has happened since their time and is still happening!

Feeding the imagination

There are some debates about North’s art and her science, well documented in a PhD thesis written here at the University of Nottingham by Lynne Gladston, but I don’t want to go into that here.

For me North was one of many 19th-century pioneers who made invisible nature visible and the inaccessible accessible to the masses but also to other scientists. Reading her memoirs, one is impressed by her botanical knowledge! It seems she could name any tree or plant or creeper she encountered, without looking it up on Google! And of course, she painted a myriad of them.

Nepenthes northiana (c. 1876), Marianne North Gallery, Kew Gardens. The painting shows the pitcher plant’s lower and an upper pitcher.

Amongst her paintings at the Kew gallery are “no less than 727 genera and approaching 1000 species” of plants. Many of the plants were barely known either botanically or horticulturally when she painted them, and four were previously unknown to science and named after her” (Huxley, Introduction, p. 13) (see image) – and, of course, they were also unknown to the public at large and had never been painted in her special style before. Working between science and art, in her own way, North did something that I call ‘making science picturesque’.

One of North’s contemporaries was one of my pet authors, Jules Verne, who ventured out in his imagination around the world – autour du monde – while North ventured out in body and soul and made it ‘autour du monde’, not in 80 days, but in about fourteen years – twice.

Verne’s imaginary and sometimes fantastic and always extraordinary voyage and adventure stories were also nature and science stories and were illustrated with pictures of places, people, plants and animals – they too brought faraway and exotic nature to the public.

Verne brought the world to the public through colourful stories and black and white illustrations. North brought the world to the public through not quite so engrossing stories about her travels but mostly through exuberant paintings. Both stimulated the imagination and brought joy and wonder to readers and viewers.

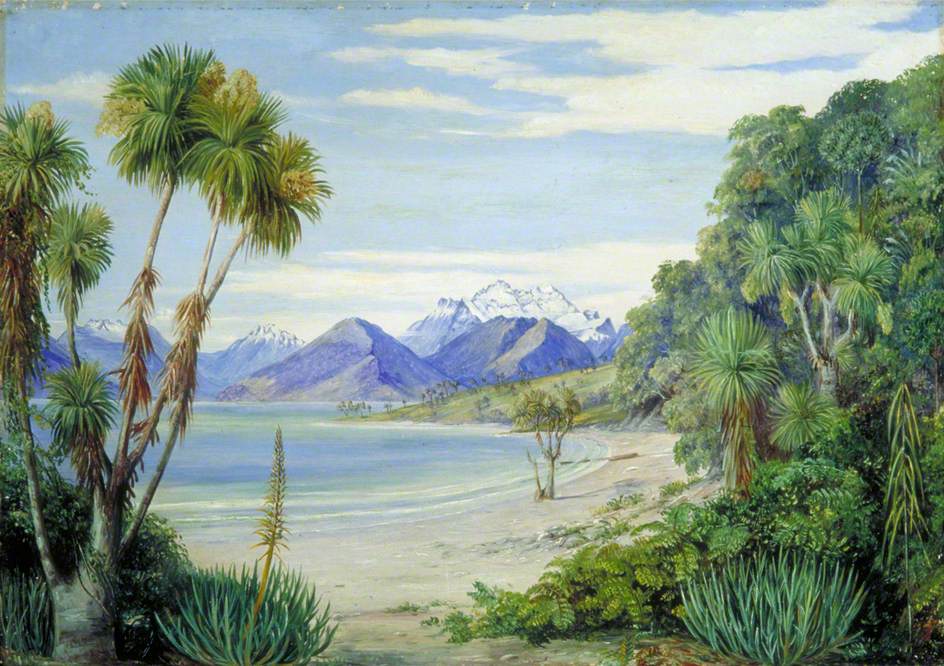

North and Verne never met or mentioned each other. But a new, 2015 German edition of Jules Verne’s L’Île mystérieuse (1875), Die geheimnisvolle Insel (1876), has a cover by Thomas Schultz-Overhage using Marianne North’s painting of Mount Earnshaw, 1880, from the Island in Lake Wakatipe, New Zealand (Lake Wakatipu). They would both have approved of that choice, I think.

Images: Public domain and holiday photos

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply