March 26, 2021, by Brigitte Nerlich

Public engagement with ‘post-normal science’

It is relatively rare, I think, for mainstream newspapers to deal with Science and Technology Studies (STS) concepts and discuss them publicly.* An article by Sonia Sodha from 20 March for The Guardian is an exception. She uses the concept of ‘post-normal science’ to try and shed some light on the vaccination debates in Europe. She had discovered the concept when preparing a radio-programme she moderated on 22 March and talked with experts on this topic.** I focus here on the article and the reader comments it provoked.

Post-normal science

What is post-normal science? It is a difficult concept, especially as words like ‘post’, ‘normal’ and ‘science’ are themselves difficult.

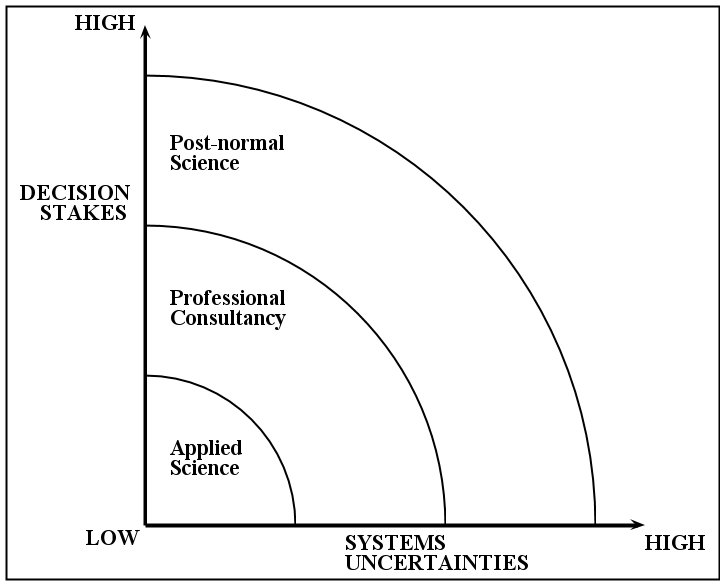

Sometimes the ‘science’ bit is descriptive, as when the article says that post-normal science “describes the kind of science that takes place in conditions of great uncertainty, where the values around science are in dispute, the stakes are high and decisions are urgent”. Science in times of covid is described as post-normal science “on steroids” and as “more vulnerable to bad science”.

More often though, the ‘science’ bit seems to refer to a method, a framework, a strategy or “a novel approach for the use of science on issues where ‘facts [are] uncertain, values in dispute, stakes high and decisions urgent’” (Wikipedia). It’s basically about improving science advice in difficult times. It should perhaps have been called post-normal science politics.

Reader comments

Back to Sodha’s article. There are two aspects to this article. On the one hand, it adopts the concept of post-normal science to reflect on some of the dodgy, politicised and polarised science that has emerged during the pandemic (further explored in the radio programme). On the other hand, it tries to fathom the decision processes that shaped vaccine policies in Europe. I’ll focus here on the post-normal science aspect of the article and the comments that readers made on that topic. This is the closest I could get to public engagement with post-normal science (there may be other instances, I don’t know of***). There were 231 comments. Not a lot, but enough to use for a quick blog post.

Three key propositions in the article were picked up by readers, mostly rather hostile to the concept of post-normal science or PNS.

‘Normal science tells us what to do’

The first proposition is based on a picture of normal science implicitly painted by those proposing PNS: “The scientists do the science. Then they tell the rest of us what to do, and lives get saved”.

One commenter rightly calls this “A common misconception”. Interestingly, this is misconception is perpetuated by those endorsing PNS in order to reject it. The commenter points out what scientists normally do in circumstances of what one may call normal science and politics: “They tell the decision makers, what the current situation is; they tell no one what to do. Think of it as a meteorologist telling you what the weather is; how you decide to dress, or even if you do go out is not the decision of the meteorologist. if you’re told it’s raining and you go out and get wet, who takes responsibility?” Of course, science advisors are in a more complicated position, but that is well known and, again, normal.

Another reader points out: “I think that this article may be confusing two different things. On the one hand there are policy decisions based on scientific input. On the other hand there is the scientific method. In a new field of endeavor with a global impact, the need to make policy decisions will accelerate ahead of what the scientific method can deliver in the short term.”

And finally, one commenter notes: “The author confuses people’s reaction to the science with the science itself. The scientists cannot help that some ideas don’t work out, and that some experiments detect a signal which turns out to be noise.” This brings us to the next proposition picked up by readers.

‘Normal science is pure’

A second proposition which aroused some debate was based on a misrepresentation of science as a sort of pure truth machine: “we idealise science as the pursuit of truth, unblemished by politics and profit, and scientists as people who deliver prescriptions so sage they almost eliminate the need for politicians”. One commenter exclaimed: “I find it hard to believe that anyone with a functioning brain cell believes that.”

This misconception of normal science is again implicit in PNS and much of STS too. Some PNS supporters seem to claim that uncertainty is “suppressed” in order to create the appearance of certainty and ‘truth’. But one commenter stresses the messiness of science where uncertainty is normal: “Science is difficult. Most of the time experiments don’t provide the expected results. You spend days and weeks, sometimes months or even years trying to make sense of what you are seeing. There are ‘Eureka’ moments of lucidity and understanding but they can be frustratingly rare. As we often say; if you think the answer is clear, straightforward and unequivocal it just means you haven’t understood the problem. The certainty and binary disagreements of BTL don’t have much to do with the realities of the scientific world.”

‘Post-normal science boosts bias’

A third proposition highlighted by readers was: “The high-stakes, highly uncertain nature of post-normal science also paves the way for scientists’ own bias to creep in.” Here we are dealing with an aspect of PNS as such, not with underlying conceptions of normal science.

One commenter immediately linked this to climate science: “Yep, and they’re thinking of their funding too. Just think climate science.” This reiterates a common talking point, indeed myth, amongst those who reject certain aspects of climate science, namely that climate scientists are just in it for the money. This myth was also, for a while at least, endorsed at the highest levels of STS (interview with Sheila Jasanoff, 2011, p.11, col. 1). Of course, bias is never far away in normal science and scientists have become increasingly aware of this and have vigorously tried to counteract this tendency of bias-creep.

As one commenter argues: “Individual scientists, with all the foibles and vanities that being human entails, can adversely impact the trajectory of a field in the short term. But over years, the scientific method has proven to be a very effective mechanism for course correction and for squeezing out the impact of human weakness.” PNS researchers would not agree with this, I think.

Post-normal science, for and against

Some comments address the concept of post-normal science directly. Most reject it, as in these comments:

“I can’t say I’ve heard of ‘post-normal science’ but it seems to be journalese for research carried out under intense time pressure. The wonder is that, under these conditions, science comes up with pretty good solutions and that safeguards such as peer review hold up as well as they do.”

“It appears to me that there is little very new in the term ‘post-normal science’. It seems to be just a new way of describing an area of study within a highly visible topic of great concern, about which not a very good scientific understanding or model has been established.”

This lengthier comment tries to show how normal PNS actually is:

“Post-normal? Science is always like this. [….] ‘Cutting-edge’ science is generally open to multiple interpretations, there are always mavericks with ideas some way away from the consensus, sometimes they’re right, often they’re wrong. Experiments get repeated and don’t work the same way the second time, or in other hands, because the world is complicated. Normally it’s the science that is more mature and less controversial that is used to inform debate and drive the development of new technologies. In the pandemic however, hot-from-the-bench science has been of the upmost importance, but it is also vulnerable to misrepresentation and misuse.”

Another commenter points out that PNS is not “a science”, while another still is puzzled about why PNS researchers are so critical of covid science:

“It might seem odd to be talking about weaknesses in science when it has delivered us several effective vaccines against Covid in just a year. […] not a mention in the article about the scientists who have delivered these vaccines. Ugur Sahin, Sarah Gilbert and others. The scientists who developed the concept of messenger RNA vaccines. Katalin Kariko, Drew Weissman and others. They have no political angle. Their motivation is scientific discovery and saving lives.”

Others, a minority though, defend PNS and refer to an article in Nature “Five ways to ensure that models serve society: a manifesto”. Another commenter just refers their fellow readers to “Wikipedia Post-normal science And an interview about covid with Jerry Ravetz: Post-normal science in the time of COVID-19”, which is an interesting read.

Conclusion

Overall then, having read Sonia Sodha’s article, readers struggled with the notion of PNS, or rather not so much with the notion of PNS but with the implicit assumptions being made about normal science inherent in the notion of PNS. This might be something for PNS researchers to reflect on when trying to engage publics with that concept, especially since the implicit portrayal of normal science as something that it is not, or of normal scientists as doing something they generally do not, permeates much of PNS writing. I’ll provide just one example:

“Normal Science has demonstrated great power in identifying viral structures, attachment sites, and pathogenic mechanisms. All these are essential for medical diagnostic and treatment regimes. However, to answer questions related to managing these technologies, including setting priorities when, for instance, respirators and hospital beds reach their limit, and for identifying how to reorganize institutional structures, Normal Science offers no guidance at all.”

As the commenters above say, this is not the job of science or of scientists.Implying that it is, in order to say that science is useless in a pandemic is rather misleading. However, I bet science could actually contribute greatly to elucidating some aspects of the dilemmas listed above.

A final thought: I wonder why Normal Science was successful in providing guidance regarding pandemic management in Australia, New Zealand, Taiwan, South Korea, Vietnam and Japan, for example, but not in the UK and, until recently, the US, despite sharing a world where facts are uncertain, stakes high and decisions urgent. Is it that in these parts of the world values were not in dispute?

Notes

*Since around 1996 PNS has only been mentioned about 40 times in mainstream newspapers, mainly during the time of climategate.

**This programme showed that scientific peer review and, in a sense, peer pressure are accepted by some scientists but that others resist it.

*** There are now some comments to explore underneath a blog post about the radio programme!

Image: Wikipedia

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply