May 23, 2016, by Brigitte Nerlich

AMR, alarm and awareness

On 19 May the much awaited report on antimicrobial resistance (AMR), chaired by Jim O’Neill, was published under the title “Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: Final report and recommendations”.

Headlines

In the UK this report was announced by the newspapers under (not very snappy) headlines, such as “Warning: Rise of SUPERBUGS resistant to antibiotics poses ‘bigger risk than CANCER’” (Express); “Experts call for $1bn rewards for solution to antibiotic crisis” (Daily Telegraph); “No antibiotics without a test, says report on rising antimicrobial resistance; Report by economist Jim O’Neill says global cost of problem could be loss of 10 million lives a year by 2050 and $100tn a year” (Guardian); “England’s chief medical officer warns of ‘antibiotic apocalypse’; Efficiency of antibiotics falling as deaths in EU and US hit around 50,000 annually from infections drugs can no longer treat” (Guardian); “Act now to defeat superbug catastrophe; Major report spells out dire consequences of antibiotic resistance” Independent); “’Antibiotics apocalypse’: 10 million people a YEAR to die due as drugs lose their effectiveness; Routine ops such as hip replacements and caesareans may be threatened by superbugs as a result – and chemotherapy could be hit” (Mirror); “’10m a year to die due to antibiotics resistance’; Routine ops such as hip replacements and caesareans may be threatened by superbugs as a result” (Mirror), and so on.

Alarming numbers, words and visuals

The figure of 10 million deaths* by 2050 (pages 12 and 19 of the report), as well as another one according to which superbugs may kill every three seconds (ibid.), were reported widely, together with words like ‘catastrophe’ (p. 19 of the report) and ‘apocalypse’ (not used in the report). As The Atlantic put it: “The report’s language is sober but its numbers are apocalyptic“. Although not used within the report itself, the words ‘apocalypse’ and ‘post-antibiotic apocalypse’ have surrounded this report for a while and the word apocalypse also turned up in the headlines listed above.

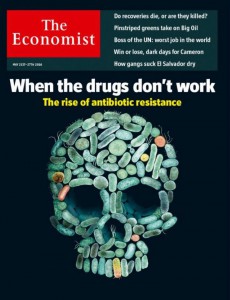

In some instances, such alarming words and numbers were accompanied not only by images of real bacteria or pills, but by frightening visualisations of their power or loss of power. The BBC, for example, displayed an image of a ‘superbug’ with a skull face.  The Economist, meanwhile used pills to paint a shocking portrait of death.

The Economist, meanwhile used pills to paint a shocking portrait of death.

Does alarm work?

These alarming linguistic, numerical and visual portrayals of an apocalyptic future or, indeed a post-antibiotic apocalypse, in which antibiotics are scarce and no longer work, reminded me of an article published by Tom Fowler, David Walker and Sally C. Davies (Chief Medical Officer for England) published two years ago. It was entitled “The risk/benefit of predicting a post-antibiotic era: Is the alarm working?” (£)

After asking this question, the authors go on to argue that “the main potential criticism of predicting a post-antibiotic era can be answered thus: (1) there is a need for such predictions to help inform the response to the issue, particularly if we are going to require societal as well as healthcare responses; (2) there is a need for such predictions to provide an appropriate evidence base for the need for resources to address the issue; (3) it is reasonable to make such predictions as a worst-case scenario if action is not taken.” (p. 5)

I am wondering what the social scientific evidence is that underpins point (1) in particular. Can one really say that such predictions are needed because they can contribute to eliciting appropriate societal responses?

Questions about the effectiveness of alarmism have been asked in the context of climate change communication and also in the context of the communication of epidemics, such as avian flu and swine flu, where health professionals have worried about ‘swine flu fatigue’ – similar to climate change fatigue. Risk communication is a complex problem, where it is difficult to find the right balance between what some have called ‘complacency mongering’ and ‘scare mongering’. Research into crisis communication in the context of the Ebola outbreak seems to show that “Over-reassurance erodes public trust far more than alarmism”. The question is: Is the AMR crisis like Ebola or like climate change or something else altogether?

These are things to think about when launching, as the report recommends, “a massive global public awareness campaign” (pages 4 and 19 of the report), with a yearly budget of $40 to 100 million. At the moment (according to a recent US report), “research on public awareness, knowledge, and attitudes about antibiotic resistance is limited, as is research on communication and engagement strategies” (Nisbet and Markowitz, 2016, p. 56). The new ESRC research initiative devoted to AMR would be a good place to start filling these gaps.

*Added 1 December 2016: A critical report discussing these numbers has just been published here.

Image: Dr Graham Beards at en.wikipedia: Antibiotic resistance tests; the bacteria in the culture on the left are sensitive to the antibiotics contained in the white paper discs. The bacteria on the right are resistant to most of the antibiotics.

Perhaps a better question to ask is why we don’t act on scientific information and have to wait till there is a crisis.

We have known about antibiotic resistance for almost as long as we have known about antibiotics. We have also known for decades that we are losing the microbial arms race.

We have known about global warming for decades and so have the politicians.

We have also known for decades about limits to growth and the risk of collapse.

We have known that we live on a fixed finite planet for hundreds of years but we still act as if economic growth can continue indefinitely.

Perhaps there is something about us that tells us that we are incapable of acting on such information?

These are indeed questions I ask myself sometimes but I haven’t got an answer to them. It is quite weird.

Hmmm! I had hoped that there might be some answers from the Social Sciences. I have a physical sciences background, which is OK for the questions but not the answers.

I was perhaps a bit flippant in my answer. There is of course some research into what some call the science communication problem, although it’s not just a problem of communication, of course. Here is a nice intro:

http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2015/03/science-doubters/achenbach-text and here http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2011/03/denial-science-chris-mooney

But although we know something about how opinions and attitudes are shaped and entrenched, it’s still quite difficult to use that knowledge to un-entrench them, so to speak….

Thank you for the links. I haven’t seen those before but I am aware of some of the content.

Here is a different take on this:

http://ruminator.co.nz/american-political-batshit-climate-change/

I hadn’t seen that one. ‘Two types of science’- that is certainly is a good way of thinking about things.

My apologies for hogging this comment thread. Perhaps I may be permitted one more?

I’ve had a look through your research aims but couldn’t see anything specific to education (maybe I didn’t look hard enough!).

I though this article had a good point in that we should be educating students in all disciplines about systems theory.

http://prosperouswaydown.com/gonella-scientific-illiteracy/

I would go further and suggest that some of these topics could be introduced at earlier stages. We do seem to have a very narrow utilitarian view for educating the young these days.

Don’t worry, this is an interesting discussion. I really liked the article you linked to about ‘systems thinking’ (it reminded me a bit of a blog post I once wrote… but I should say I was never ever taught systems theory or anything like it at school http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2013/12/20/tools-for-thinking-about-an-increasingly-complex-world/). I agree that teaching science ‘facts’ should be abolished and be replaced by a more systems-oriented education (I would say holistic, but that word is now tainted).

Now, as to our research aims… this programme of research is actually not about science communication, and certainly not about science education. The title is rather misleading and I have been accused of deviating quite a bit from the original programme by focusing my posts on’making science public’ in the sense of science communication. How did this come about:

Originally two people with expertise in Science and Technology Studies (STS) were supposed to lead the programme: Paul Martin and Sujatha Raman. Before the start of the programme, Paul accepted a Chair at the University of Sheffield and the University of Nottingham appointed me as Director of the programme with Sujatha as Deputy Director. When I took over the leadership of the programme and started to blog, I had to think on my feet. The programme had only just begun; so I couldn’t report on emerging findings. I had also taken over a programme which was grounded mainly in STS, a field or discipline in which I have no real expertise. I have a background in linguistics and the history and philosophy of science. (I did my PhD on the history of 19th-century French linguistics). I went on to write about various aspects of climate change from a linguistic and philosophical angle, thus trying to contribute to the sub-project that I led as part of the overall research programme. As I am passionate about science, I also began to report on a number of emerging science topics and issues such as the Higgs Boson, gravitational waves or the landing of Curiosity on Mars. I always try to link my (naïve) accounts of such developments to wider questions related to ‘making science public’. However, overall my posts began to be not about STS but more about the theory of science communication and also actually practicing science communication. This has caused some confusion amongst my STS colleagues and probably more widely, especially as most of the blog posts for the ‘Making science public’ blog are written by me, a non-expert in STS!

[…] AMR, alarm and awareness […]

” I agree that teaching science ‘facts’ should be abolished and be replaced by a more systems-oriented education” – not sure about abolished, but the ability to critically evaluate news stories is required now more than ever.

But here’s the odd thing – I see in my social media timelines that those people who are most persuaded by conspiracy theories are often also those who most often say that information must be viewed critically, even as they themselves are posting unchecked memes as “facts”!

As someone currently designing an antibiotic stewardship program, your articles on antibiotic discourse are beyond mind-opening (I binged read all of them). A public health official I was working with expressed his concern about the sensationalism in resistance communication with me last year. It is worrying that such language is still used by journalists and experts.

It is mind-boggling to me that many of those who are not using the apocalypse frame are opting for the extreme opposite, I will call it the “small action frame.” There is a bus-ad running in my province (British Columbia, Canada) asking for people to sign an online pledge to fight the global war against antibiotic resistance (http://antibioticwise.ca/). Personally, I thought the sheer distance between “fighting a war” and “signing a pledge” makes the campaign message quite silly and ineffective (also costly!).

Perhaps more talented social scientists like you should join the conversation… There is no going back if the public is desensitized to the issue. We are already seeing the use of catastrophe frame taking a toll on public perception:

https://wellcome.ac.uk/sites/default/files/exploring-consumer-perspective-on-antimicrobial-resistance-jun15.pdf

I’d love to hear more about your stewardship program. When I wrote this post I hadn’t taken antibiotics for a very long time. So I could write about AMR from a distance. Now I am taking topical antibiotics and oral ones. The topical ones come in little vials of which I only use one drop and the rest goes in the bin. I feel rather awful about this. But without them I would be lost. So I don’t know what I would have felt if I had pledged to fight the global war on AMR! I feel conflicted enough. I wish I could work on all this a bit more, but I have no funding. I have written a few articles but they don’t really touch the heart of the matter. Hmmm, the global war vs small action frame reminds me of the heady days of fighting global warming around 2007, when we were told for-ever, by everybody, including Prince Charles, to not overfill our kettles. As the late David MacKay said: “Turning phone chargers off when they are not in use is a feeble gesture, like bailing the Titanic with a teaspoon.” Keep in touch!

Although I have pledged, I also felt conflicted when faced with everyday decisions… Some of my immigrant friends are bringing antibiotics from China because they don’t have access to a family doctor and visiting a clinic (with a high possibility of not getting an antibiotic) is simply not an option when their employer “expects” some sort of treatment for their illness. Hence, I rarely bring up stewardship with them. Quite ironic when the speaker I recently brought in is tasked with lecturing students (many are recent immigrants) about proper antibiotic use!

There is definitely lots of connection between the current antibiotic resistance discourse and climate change discourse. I have never heard of the kettle advice until now. I don’t know if I should to laugh or sign. Nevertheless, let’s hope AMR does not become politicized like climate change, as MRSA did during the 2005 UK general election.

Personally, I think a new frame is needed. Perhaps one that empowers the public, encourages discussions on the structural factors that causes antibiotic misuse, and thwart the “blame game.” Unfortunately, I am not an expert in linguistics.

So what do you think? How can we improve upon the way we communicate AMR?

By the way, the e-book is very helpful. The section on communicating with the press is just what I needed!

I have just arrived in Germany to spend Easter with my very old parents (there are stories to tell about AMR, Cdiff, sepsis and more), so don’t have a lot of time to think. I also hope AMR won’t be politicised like climate change; I would be surprised if it was. But like climate change it is a political problem. Without the will of (national and global) policy makers to do things on various fronts it will not be solved. Individual actions help but they are nothing compared to what big political and industry actors could and should do. You might be interested in this perhaps – it’s a bit too linguistic perhaps http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1363459317715777?ai=1gvoi&mi=3ricys&af=R

Happy early Easter! Thank you for sending me the research. Why are your studies always so interesting? And no, a research can never be too linguistic.

It is fascinating how the choice of subject might influence the way people perceive a sense of responsibility. Given the prevalence in the UK media of framing antibiotic resistance in terms of other individual/organisms instead of “us” or “we,” we need experiments exploring whether these word placements really do impact attitude and even, behaviour! I wonder if US and Canadian media follow the same suit… Based on my own personal readings, it seems that US and Canadian media are generally more “toned down” in terms of diction. But I am not sure if “we” or “us” is mentioned more in relation to antibiotic resistance…

If you don’t mind, I would like to forward this link to my colleagues. If you happen to have other interesting research, feel free to send it to me. Thank you again for this thought-provoking study.

You can certainly forward the study to anybody you like! It would be great to get a conversation going – continuing. And to get some comparative studies going!

You might be interested in this study on how narratives might be an effective tool to change attitude and even behaviour regarding antibiotics and antibiotic resistance.

http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/7413/2264

I’ll read this as soon as I get home!

This might be of interest to you: http://bsac.org.uk/antimicrobial-stewardship-from-principles-to-practice-e-book/