June 8, 2015, by Warren Pearce

Improving climate change communications: moving beyond scientific certainty

T his is a co-authored post with Gregory Hollin. It is based upon our new paper in Nature Climate Change, which is the first piece of original research from science and technology studies (STS) published in the journal.

his is a co-authored post with Gregory Hollin. It is based upon our new paper in Nature Climate Change, which is the first piece of original research from science and technology studies (STS) published in the journal.

In the last 25 years scientists have become increasingly certain that humans are responsible for changes to the climate. Nonetheless, there is a widespread feeling, memorably summed up in the Kudelka cartoon “None So Deaf”, that this certainty has failed to make climate change meaningful enough to prompt significant personal, political or policy responses. An opportunity to address this problem was presented by the publication of the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report in 2013, as leading climate scientists appeared before the world’s media at a Stockholm press conference. The press conference, one would imagine, is an ideal opportunity to make scientific findings intelligible and meaningful to non-scientific audiences and, in a new paper, we examine how scientists utilize this opportunity. What we found is that, in attempting to demonstrate the importance of climate change, scientists actually became inconsistent about ‘what counts’ as scientific evidence and this led to confusion and condemnation in the press.

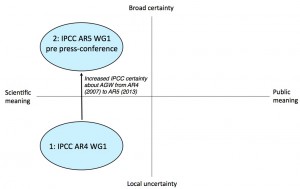

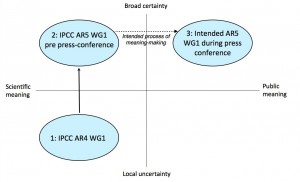

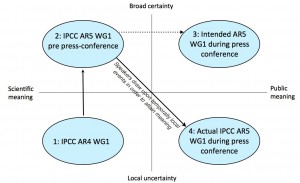

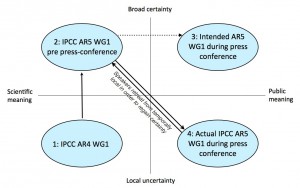

In this blog post we’ll go through what happened in the press conference by detailing four stages in the intended process of making climate change meaningful. We’ve reproduced some figures for our article here because we think they make it much easier to follow the argument. The matrix for all of these figures places ‘meaning’ on the x-axis and ‘certainty’ on the y-axis. We won’t go into details here but, if you’re interested in the creation of the matrix please look at the method section of the article itself, or leave a comment below. Line numbers refer to a transcript of the press conference which is available in the paper’s supplementary information.

Phase One: Increasing certainty

Since the last IPCC report, certainty over the nature of climate change has increased and, unsurprisingly, scientists at the press conference stressed this increase:

Since the last IPCC report, certainty over the nature of climate change has increased and, unsurprisingly, scientists at the press conference stressed this increase:

…the evidence for human influence has grown since Assessment Report 4, it is now deemed extremely likely that human influence has been the dominant cause of the observed warming.” (Steiner L153–155).

However, and as noted above, academics from the social sciences and humanities have argued that climate change has yet to attain enough public meaning to prompt significant personal, political and policy responses. Figure 1 thus shows a vertical shift along the y axis, representing increased certainty but also the fact that climate change continues to attract little public meaning.

Phase Two: Making climate change meaningful: the intention

Within the press conference, scientists tried to use the certainty of climate change to demonstrate that it is meaningful and that ‘we’ must take action:

Within the press conference, scientists tried to use the certainty of climate change to demonstrate that it is meaningful and that ‘we’ must take action:

[The] report demonstrates that we must greatly reduce global emissions to avoid the worst effects of climate change. (Jarraud L90–92).

In Fig. 2 we represent this move with a horizontal shift along the x axis (to position 3); certainty remains but attached to this certainty is a great deal of public meaning. We argue that this is what the scientists wanted to achieve in the press conference: retaining the certainty of the report while adding meaning.

Phase Three: Making climate change meaningful: the reality

There was, however, an inconsistency in the argument of the scientists. Scientists consistently drew on short-term temperature increases in order to give climate change meaning:

There was, however, an inconsistency in the argument of the scientists. Scientists consistently drew on short-term temperature increases in order to give climate change meaning:

…the decade 2001 onwards having been the hottest, the warmest that we have seen. (Pachauri L261–263).

However, the scientists also understood these short-term temperature increases to be less certain than the overall theory of climate change:

periods of less than around thirty years. . . are less relevant. (Stocker, L582–583).

Thus, the meaningful, short-term, temperature changes were actually incorporated at the expense of certainty. While the intended move was therefore to the top-right quadrant (position three), the actual move was to the bottom-right quadrant (position four): meaning had been added but at the expense of certainty.

Phase Four: Inconsistent attempt to maintain public meaning and certainty

Drawing on meaningful information like ‘the hottest decade’ proved problematic for the scientists for it is hard to see why the short-term increase in temperature during ‘hottest decade’ is very different from the short-term decrease in temperature witnessed during the 15-year ‘pause’. Journalists repeatedly asked scientists about the pause and, in particular, how they could be increasingly certain about climate change in the face of such an uncertainty:

Drawing on meaningful information like ‘the hottest decade’ proved problematic for the scientists for it is hard to see why the short-term increase in temperature during ‘hottest decade’ is very different from the short-term decrease in temperature witnessed during the 15-year ‘pause’. Journalists repeatedly asked scientists about the pause and, in particular, how they could be increasingly certain about climate change in the face of such an uncertainty:

Your climate change models did not predict there was a slowdown in the warming. How can we be sure about your predicted projections for future warming? (Harrabin L560–562).

Faced with these questions, scientists insisted that short-term temperature changes were irrelevant for climate science:

we are very clear in our report that it is inappropriate to compare a short-term period of observations with model performance. (Stocker L794–796).

Given the type of statement we saw during phase three it is perhaps unsurprising that this retreat led to confusion, incoherence, and criticism within the press conference.

Conclusion: uncertainty is meaningful

…the scientific reductionism of climate change makes consensus possible, but the result is, in some sense, irrelevant. The things that can be known with scientific certainty are not necessarily the most important to know. (Cohen et al., 1998, p.361)

Climate change is an area where consistent attempts are made to communicate the certainty of the science. As a result, a spotlight on scientific uncertainties may be seen as unwelcome. However, in the run-up to the United Nations climate summit in Paris, making climate change meaningful remains a key challenge and our analysis of the press conference demonstrates that this meaning-making cannot be achieved by relying on scientific certainty alone. When trying to engage the public about climate science, communicators should be aware that there is a tension between expressing scientific certainty (and focusing on long-term trends) and making climate change meaningful (by focusing on short-term trends) and, what is more, that this tension may be unavoidable. A broader, more inclusive public dialogue will have to include crucial scientific details that we are far less certain about and these need to be embraced in order to make climate change meaningful.

Image credit: screengrab from video recording of IPCC press conference, Sep 30th, 2013.

It Is Fraud, Not Climate Science At All

It is not deficiencies in communicating the science that is the problem. It is the “science” itself that is the problem–and that is a combination of general incompetency among today’s scientists, and political abuse of the fundamentally false science by radical activists, currently empowered by the Obama administration (and similar “progressive” leaders worldwide). The hapless public is faced with a “perfect storm” of scientific delusion and political lies.

Please clarify if you are the person advertising a book on Amazon containing the following explanatory note. Because it explains a lot.

“The Earth, indeed the entire solar system, was re-formed wholesale, in the millennia prior to the beginning of known human history; c. 15,000 BC marked the decisive event, when the Earth first began to orbit the Sun as it does today. Worldwide ancient myths and sacred traditions all refer directly but metaphorically to the core elements of the world design. Megalithic monuments such as the pyramids, Sphinx, and temples with fundamental celestial alignments commemorate the establishment of those alignments within the passed-down memory of mankind. All of the ancient mysteries originated or passed through the filter of this design event.”

Fabulous! And well done.

Your misrepresentation of meaning is unfortunate here. Stocker makes a rather clear and specific statement that short-term observations are inappropriate for comparison with climate models [*]. It’s very difficult to understand how you can equate this with meaning that “short-term temperature changes were irrelevant for climate science”.

[*] This is really easy to understand. Despite the long term warming as the Earth surface temperature re-equilibrates in response to enhanced greenhouse forcing, short term variability (ENSO, volcanic eruptions, solar output etc.) modulates the surface temperature response. Since this short term variability is somewhat unpredictable (volcanic eruptions can’t be predicted, nor can solar variability outwith the solar cycle etc.) one doesn’t expect the short term temperature response (decadal timescale) necessarily to follow the modeled response closely – agreement should be apparent on longer timescales as the random (stochastic) variability averages out.

Although this short term variability is difficult to model predictively it is hugely relevant for climate science! Studying how the earth surface temperature responds to variations in ENSO, solar output, volcanic eruptions and so on has been profoundly useful for climate science in understanding responses to variations in forcings and the range/nature of temperature responses to natural variability.

I do not understand the root cause of this difficulty in explanation of the pause.

The recent history of temperatures showed as a picture looks very much like a sawtooth superimposed on a slightly rising trend. Some of the peaks and troughs last longer than a decade. The pause is real, but the word is just slightly misleading–it is a sharp slowdown in warming when compared to the two decades preceding it.

It is not unprecedented–there were two pauses in the 20th Century that lasted even longer than the current ‘pause’. The current ‘pause’ does not disprove anthropogenic contributions to global warming any more than the previous two decades of sharp warming proved it.

[…] Climate change scientists must be more honest about the limits of their knowledge and uncertainty around predictions if they are to win the trust of the public, according to a new report. […]

The problem for the scientists is not what they are saying now, but what they said 10 or 15 years ago. Then they were saying that their models predicted a rapidly INCREASING global air temperature, which would rapidly overwhelm natural variability and result in major and obvious catastrophe, by 2015. And they also said that this science was settled, and not dependent at all on natural variability, which was minor and insignificant. And that a ‘pause’ could not happen – if one that was 10 or 15 years long DID happen, it would mean that all their theories were wrong, which could not be the case.

Given this track record, it is not surprising that the pause is an issue for them…

Dodgy Geezer has it right. It was the continuing stream of predictions of certain disaster, predicted to occur within 10 years, by the end of the decade, by 2005 etc., that failed to come true with the ensuing pause, that destroyed the scientists credibility. Al Gore winning the Nobel Peace prize for that piece of unadulterated propaganda, while being cheered on by the scientific community, didn’t help when none of his prophecies of warmaggedon came close to occurring.

The public seems to seems to have clued into the fact that if you have a theory that projects certain results, and the results don’t occur, you need to re-examine the theory. Coming up with 40 – 50 different scientific papers that explain the pause also seems to indicate that maybe you don’t understand the process, and that “immediate action” based on the computer projections as currently written might be ill-advised.

Since I had a discussion with Greg on Twitter, I’ll make my point a bit more thoroughly here. In a simple sense the paper appears to be suggesting that there was an inconsistency in how the information was presented at the press conference. The speakers both used that the decade from 2001 onwards was the hottest on record, while suggesting that periods of less than about 30 years are not sufficient for assessing anthropogenically driven climate change. The problem with this is that the “hottest decade” referred to the hottest in the instrumental temperture record. The text in the transcript is

It is true, that they do mention “the last three decades”, but – again – this is relative to the entire instrumental temperature record. So, the “hottest decade” message was not actually using a short time interval; it was discussing the long-term trend in decadally averaged global temperature. This is not the same as things like the so-called “pause” because that considers only a short time-interval (i.e., since 1998, for example).

So, I’m not seeing the inconsistency in what was presented at the press conference. It may be the case that this wasn’t clarified sufficiently, but even that isn’t obvious given that the text I quoted above explicitly says “since 1850”.

To echo ATTP’s point, the statement regarding warmest decade since 1850 was presumably made in reference to the middle panel in this figure: http://www.climatechange2013.org/images/figures/WGI_AR5_FigSPM-1.jpg clearly taking a long-term view and using decadal averages for the reason that this averages out shorter term variability.

The comparison drawn between this long term view and the short term variability that’s at the core of the so-called “pause” is totally off the mark.

Just to clarify, is this work arguing that the public can’t distinguish between climate change and year to year variability in the weather?

One aspect that seems to be missing is that this press conference was for journalists, most of whom were well-informed about climate science. It wasn’t aimed at the general public. The questions from (most of) the journalists demonstrated they understood a lot about climate science. And understood that the hottest decade since 1850 is consistent with global warming, that each decade being hotter than the previous one – since 1951-1960 – is consistent with a warming trend, and that none of this is inconsistent with year to year internal variability.

Also, I’m curious to know why you wrote the following, when both your transcript and the video of the proceedings (as well as the IPCC report) show the opposite:

“This `temporal segmentation’ enabled the pause to be dismissed as scientifically irrelevant, suggesting that journalists’ questions on the matter could be ignored.”

The recent period was discussed as being very relevant (not to the long term trend, but to exploring causes of internal variability, and attribution); and questions about it were not ignored.On the contrary, they were answered at some length. (Most questions were about other matters, but when the questions arose at the press conference, they were answered, not ignored.) There has been a lot of scientific research on variability this century.

Hi sou

What is worse to be in your opinion… A ” denier” or a “deniophile”

It’s helpful is that the AR5 Working Group Press Conference is online:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UxI1qDSfX_U

..and so it’s easy to assess the extent to which the press conference presented a decent representation of the broad findings of the Summary for Policymakers, and whether the questions were addressed with reasonable clarity (remembering that the exquisite care that individuals may take in written presentations may not always be matched in on-the-spot verbal responses!).

Discussions around “the pause” constituted a small proportion of the total quest/answer session but I think those particular responses were straightforward (the responses around 1hr 23min (Stocker) and 1hr 26min (Jarraud) to Q 13 about “why include the 15 year period in the report” were particularly good IMO). After watching it, I find it more difficult to understand the apparent confusion (possibly not v widespread!) between the fact that short periods, dominated by internal/external variability, are not v useful in addressing trends that can be compared to models, and the fact that these periods may on the other hand (i) be very useful in understanding surface temperature response to forcing and the temporary off-setting of forced responses by internal variability and (ii) be required to be discussed when one is addressing how the surface temperature now (last decade) compares to previous periods…

It’s also a mark of the cumulative nature of scientific investigation that only 8 months or so after the press conference we’re quite a lot clearer about the nature of the so-called “pause”, its significance, and even its very existence!

I think a lot of this misses the point that climate change now has a history and this history has seen a gradual erosion in public support and interest. Of course science is public or at least the public pay for most of it, so they do have a right to expect certain standards from their employees. The first might be freedom from the influence of particular pressure groups, the IPCC is not a scientific body, its a political body which is heavily influenced by environmentalist groups, it has a clear bias and therefore lacks credibility.

If science is paid for by the public they expect the data to be available, which it should be for any credible science, they also expect and have every right to that scientists should be prepared to explain things and answer questions. They recognize uncertainty, they expect arguments, if what they see are attempts to prevent debate and challenge they become deeply suspicious.

To many scientists treat the public as if they are idiots and while its not really their job to understand the methods of science they do recognize the contempt inherent in ideas about making messages simple and unequivocal. In fact the main problems in communicating climate science is probably with the “believers” than the scientists, the mass of misinformation, insulting terms like deniers and the advocating of coercive controls is increasingly driving people away. Its no longer an issue about effective communication, its about attempting to communicate with people who no longer trust what you say, its incredibly damaging for climate science and is increasingly having an adverse effect on the public perception of other sciences.