October 3, 2014, by Brigitte Nerlich

Philae: Where space science meets language science

As those who care about that type of thing will know, Philae, the robotic lander on board the Rosetta spacecraft, will try to touch down on the surface of the Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on November 12.

While we await the next episode in this space adventure, another episode in an adventure here on earth is unfolding which began more than two thousand years ago. These adventures are linked by the names of the spacecraft and the lander. So I’ll first talk about these names and then come to the earthly rather than heavenly adventure. Both contribute to ‘science making’ in public – space science on the one hand, the science of human language and human civilisation on the other.

Rosetta

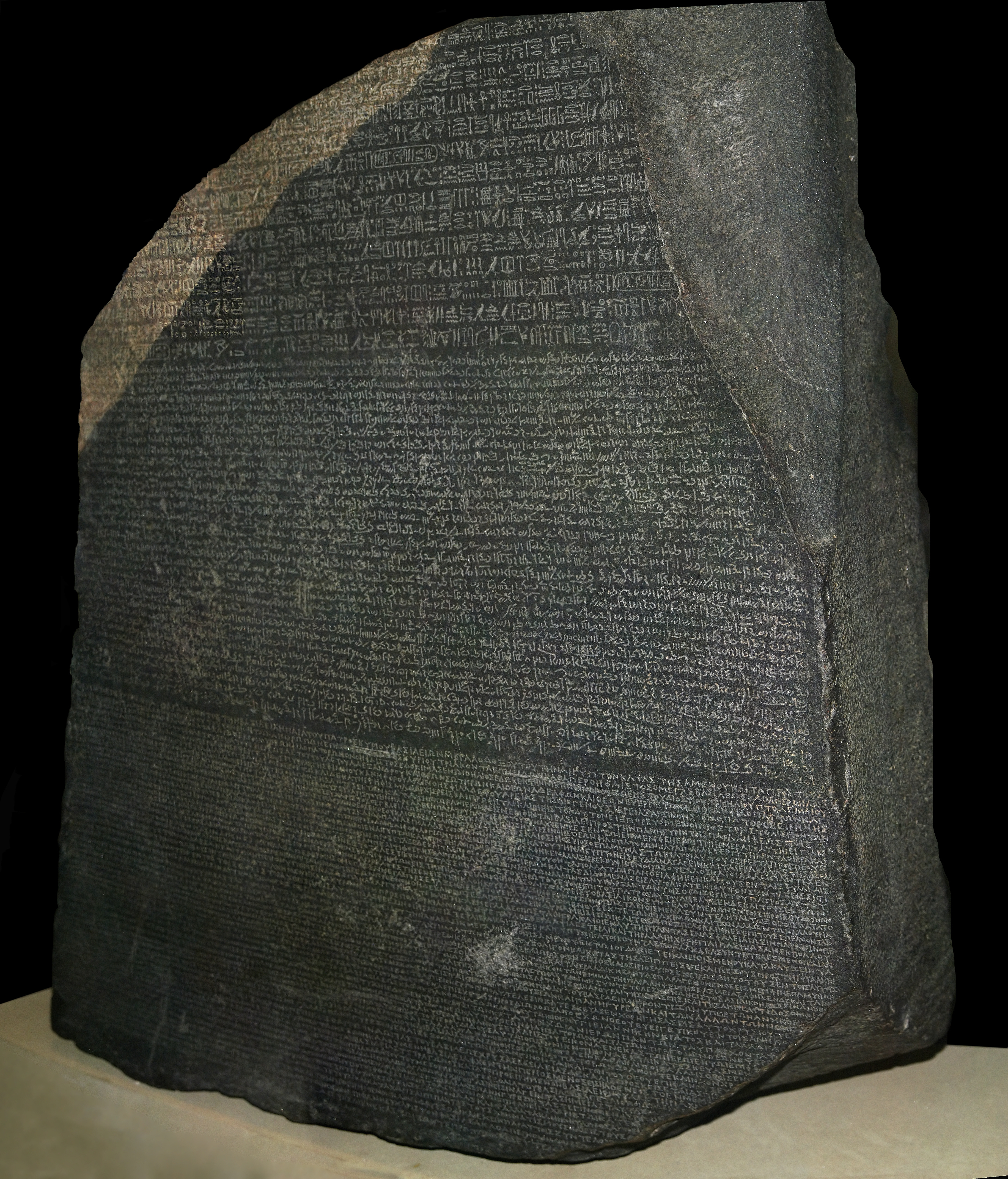

The Rosetta spacecraft was named after the famous ‘Rosetta Stone’, which itself derives its name from the Egyptian town of Rashid or Rosetta where it was found.

As the European Space Agency explains, this slab of stone was discovered by French soldiers in 1799 and was carved with inscriptions in languages that included “hieroglyphics – the written language of ancient Egypt – and Greek, which was readily understood. After the French surrender in 1801, the 762-kilogram stone was handed over to the British. By comparing the inscriptions on the stone, historians were able to begin deciphering the mysterious carved figures. Most of the pioneering work was carried out by the English physician and physicist Thomas Young, and the French scholar Jean François Champollion. As a result of their breakthroughs, scholars were at last able to piece together the history of a long-lost culture.” ESA hopes that their Rosetta spacecraft will “unlock the mysteries of the oldest building blocks of our Solar System – the comets. As the worthy successor of Champollion and Young, Rosetta will allow scientists to look back 4600 million years to an epoch when no planets existed and only a vast swarm of asteroids and comets surrounded the Sun.”

Philae

Philae, the robotic landing craft, was named after an Egyptian obelisk found on an island in the river Nile called Philae. It was brought to Kingston Lacy House near Wimborne in Dorset in the 1820s by the explorer and Egyptologist William Bankes (an interesting historical figure). This stone monument too contained inscriptions in two languages and enabled scholars to finally decipher the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone.

Space meets language

While we await the outcome of Rosetta’s mission, a different type of science and technology is currently being deployed here on earth, that is to say at Kingston Lacy, to continue deciphering the language of the Pharaohs.

Simon the Bruxelles briefly reported in The Times (27 September, 2014) that a “new study of the obelisk to recover previously unreadable inscriptions will begin this week. Experts will scan weathered sections of the Greek text using multispectral imaging and a new technique called reflectance transformation imaging [RTI] in the hope of making it legible for the first time in millennia”.

When going to the website of the Oxford Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents, which leads this study, one discovers that work has not only begun on RTI but also on the production of 3D interactive images of the 6.7 tall obelisk. And on top of this, “time-lapse photography will record the process, from erection of the purpose-designed scaffolding, through the cleaning of the obelisk by the National Trust [which owns Kingston Lacy] conservation department, to the RTI photography and 3D scanning; an exhibition, and the possibility of a short documentary film on the obelisk and its flamboyant history.”

Science in public

So we have two scientific adventures linked by the names Rosetta and Philae: on the one hand the exploration of a comet that might tell us something new about the early solar system and on the other the exploration of ancient inscriptions which might tell us more about an ancient language and civilisation. Both may increase our understanding of who we are and where we come from. These two enterprises coincided more by accident than by design but are now part of what the Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents calls an “unexpectedly exciting cross-discipline enterprise”. What is more, both these two high-tech adventures are not only scientific but also public events.

And we should not forget that “the Rosetta spacecraft […] carries a micro-etched nickel alloy Rosetta disc donated by the Long Now Foundation inscribed with 13,000 pages of text in 1200 different languages.” (wikipedia) Who knows what types of scientists and members of the public might try to decipher them in the future…….

ADDED: Interview with Dr Jane Masséglia about the Obelisk with (BBC News, 23 October, 2014)

Philae Lander: DLR, German Aerospace Centre, Wikimedia Commons

Rosetta Stone: Hans Hillewaert, Wikimedia Commons

Philae Obelisk: Eugene Birchall, Wikimedia Commons

Spookily, and in a tenuous link to your post, I have just been researching* for a blog post about anarchism and was struck by how many UK 80s pop groups had very political names (Communards, UB40, Spandau Ballet, Joy Division etc) – each of which carries a lesson from history – just as the naming of spacecraft and telescopes do.

*researching as in googling

Now that is interesting!! (And my type of ‘research’ – as I once said, I call blogging ‘knitting with hyperlinks’….

[…] I have written about the Rosetta mission and Philae, I thought I had to at least try and write something very short about the landing site (formerly […]