August 23, 2013, by Brigitte Nerlich

Consensus on climate change: Tracing the contours of a debate

Soon the new IPCC report on climate change will be published (a leaked version is already circulating). This will probably generate a lot of talk about what one may call the four Cs: Consensus, certainty, confidence and credibility (let alone the other two Cs: climate and change). The discussion about consensus is already in full swing; confidence is rearing its head, and so is certainty (and here). In the shadow of climategate issues of credibility lurk, ready to pounce. Will the fifth C, controversy, be inevitable?

I won’t step directly into the heated debate about consensus, but tackle the issue more indirectly from my own perspective, using, what I have come to call in my mind the ‘media studies litmus test’. As I have done in various other posts, I wanted to get a rough feel for the contours of the debate about consensus and climate change/global warming in the media sphere from around 1988 onwards, when climate change first became a political issue.

The contours of a consensus

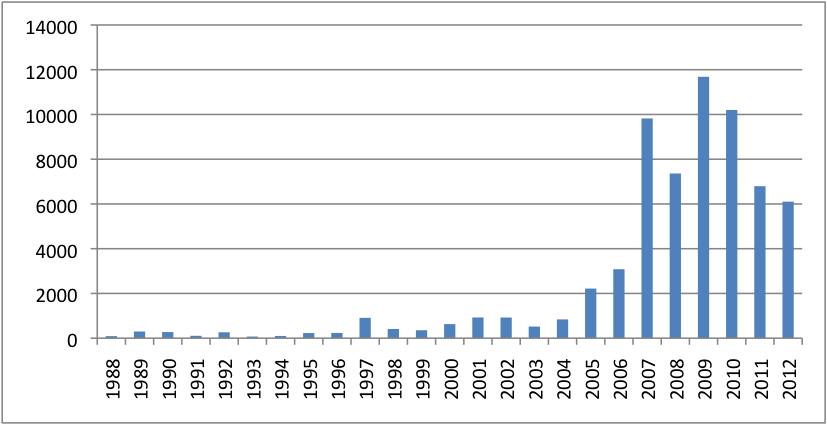

I searched the Lexis Nexis database of news, using the keywords ‘consensus’ and ‘climate change’ or ‘global warming’. I began with ‘All English Language News’ and arrived at this graph, below. I then did the same for ‘Major World Publications’ and the shapes of the two graphs were virtually identical (I am not totally sure what that means, but it meant that I had not totally miscounted the large numbers for ‘All English Language News’). As usual, there are all sorts of caveats associated with this method. As the sample is huge, I haven’t yet been able to carry out a thorough quantitative, let alone qualitative, analysis of any part of it, although below I’ll delve a bit into the beginning and the end of the time span I am looking at. So, the word consensus may be used in all sorts of different ways, some more central to the consensus debate around climate change, some others less so. However, when you look at the graph, you’ll be able to make out some interesting features which seem to reflect certain events in the timeline of the debate about climate change in the West.

One can see a first rise in use of the term ‘consensus’ in 1997, the time of the Kyoto protocol. The IPCC published its third assessment report in 2001 which corresponds to a little blip on the graph. This was followed by a first jump upwards in 2005. This year is really interesting and would deserve further scrutiny, as it was the year when the Kyoto protocol was coming into force, when Bjørn Lomborg made controversial statements about climate change, when Tony Blair, then Prime Minister of the UK, put climate change on his political agenda, when the EU’s emissions trading scheme was launched, and much more. The year ended with the Montreal Climate change conference. More importantly perhaps, the year began with the publication of Naomi Oreskes’ seminal paper in Science on the scientific consensus on climate change, which started a debate that is still going on today…. I’ll just quote from one report on Oreskes’ paper: “The global warming debate will shift in the United States in 2005 because evidence that the phenomenon is real has reached a crescendo. The catalyst for the shift is not some esoteric discovery by an atmospheric scientist, but a fairly simple paper by a history professor, Naomi Oreskes of the University of California, San Diego. Oreskes has found there is a ‘scientific consensus’ on global warming — that is, it is real and it is being caused by humans.” (Dan Whipple, UPI, 3 January, 2005) This prediction about a shift in the US debate about climate change did, however, not come true.

A big jump happened in 2007, the year that the fourth IPCC report was released (and many other events around climate change happened!). 2008 shows a bit of a slump, probably because people thought the science was settled and it was time to move on to various political climate change mitigation actions. Things changed quite dramatically in 2009, when disputes about the consensus were fuelled by climategate. After that period of heated debate, the use of the term began to drop off again. We’ll have to see what happens in 2013/14, but I would predict that there will be another big jump.

I started my counting in 1988, the year that climate change became political and the year that the IPCC met for the first time. However, I was curious about what happened to the term consensus just before that. So I took a quick look at the period from 1979 (zero attestations) to 1987. Between 1979 and 1987 attestations waver between 2 and 15. They then jump to 92 in 1988. So in the following I’ll take a closer look at 1988 and then at a period of two months, November and December 2009, when attestations were at their peak. Here I’ll only look at two tiny samples taken from newspapers from the two ends of the UK political spectrum, The Guardian (34 articles) and The Daily Telegraph (14 articles).

An emerging consensus

When reading through the small body of articles from 1988, it becomes apparent that, overall, a scientific consensus was emerging that greenhouse gases are contributing to global warming. There was awareness of some remaining uncertainties and there was an emerging political will to implement measures to curb the emission of greenhouse gases. This became especially apparent during the World Conference on the Changing Atmosphere held in Toronto. Here are some examples of how the word consensus was used:

“Consensus is emerging among scientists that the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuel and the buildup of other industrial gases is trapping infrared radiation from the sun that would otherwise escape back into space.” (New York Times, 26 April, 1988) “[…] participants [at the Toronto conference] said the newly emerging consensus on the need to act against atmospheric pollution, and the specific targets set here, would give an important impetus to national and international actions in the near future.” (NYT, 1 July, 1988) “Despite the lack of consensus in the scientific community as to the level of threat and solutions, there is a rapidly growing perception by governments and the public that the world must reduce the environmental effects of burning fossil fuels by utilities, manufacturers, and vehicles.” (Oil and Gas Journal, 29 August 1988)

However, as I have shown in another blog post, contrarian voices and calls of ‘alarmism’ were not absent from that period. Opposing discourses were there, it seems, from the word go, and they don’t seem to shift very much over time.

A surprisingly stable consensus?

When we jump now to 2009, we find a quite similar situation, even, and to my surprise, reflected in both The Guardian and The Daily Telegraph. I expected the Daily Telegraph to dispute the consensus, especially in the context of climategate. However, in my small sample this was not the case. (One should, however, not forget that at the same time James Delingpole was blogging actively about climategate, but his name doesn’t appear in my sample). Both major environmental columnists for these papers, George Monbiot (Guardian) and Geoffrey Lean (Telegraph), may have had their confidence slightly shaken by climategate, but they both stressed that these revelations did not/should not affect the general scientific consensus.

Monbiot’s first article muses about the rise of climate scepticism/denialism and wonders whether its rapid growth over the preceding two years is “a response to the hardening of scientific evidence” (3 November). His next article appeared a few days after ‘climategate’ (23 November) and Monbiot is honest about the dismay he feels about the leaked emails. However, he comes to the conclusion that this is not ‘the final nail in the coffin’ of the global warming theory [an indirect reference to an article by Delingpole]. Climategate, he argues, may have undermined the credibility of some scientists and the integrity of some lines of evidence but not of all scientists and all evidence. This view is echoed by Michael Mann quoted in an article by Leo Hickmann and others (24 November).

Three days after the climategate emails first appeared on the internet, a new think tank was set up by Lord Lawson, the Global Warming Policy Foundation, which questioned above all the political consensus around climate change. This is covered in various articles in The Guardian, which also reports on Ed Miliband, the then Climate Change Secretary, calling Lawson a ‘climate saboteur’ (4 December) (similar reports appear in the Daily Telegraph).

One article by Alexander Chancellor laments the fact that “nothing seems certain in this controversial field” anymore (26 November). Another article (polemically) quotes Ian Plimer (an Australian climate sceptic) calling the scientific consensus a “fundamentalist religion” (5 December) (on these types of metaphors see Nerlich and Woods).

What about the Daily Telegraph? One article I found, written by Ceri Radford, had the surprising subtitle: “Turning a point of view into an article of faith does nobody any favours”. It advocates trusting the consensus but being open to new evidence. It also criticises the polarised language around climate change: “Are you are ‘warmist’ or a ‘denier’? A member of an intolerant sect, or the moral counterpart of those who refuse to accept the truth about the Holocaust? The terms thrown around are so loaded and intransigent that they negate even the possibility that the other side is thinking and acting in good faith.”

There is one short article reporting on climategate and the purported sidelining of papers questioning the scientific consensus (24 November) and one complaining about the “smug, self-righteous certainty of those holding the consensus view” (25 November). One article briefly reports on Gordon Brown, then Prime Minister, calling climate sceptics ‘flat-earthers’ “amid signs of public doubt about the scientific consensus” (5 December).

More importantly (perhaps), Geoffrey Lean wrote a longer article (4 December). He talks in positive terms about the scientific consensus, how it emerged over time and stood the test of time. He also writes about the consensus process involved in writing IPCC reports, which results, he argues, in “underestimating the risks and effects of climate change”, rather than overestimating them. Lean also points out that the reason why the debate about climate change (and the consensus) is so heated is “because it is not scientific at all, but political and economic”. And with this we come back to the beginning of the consensus story.

Beyond consensus?

In 1988 a scientific consensus about climate change emerged and it was believed that political action could be built on its basis. The same happened again in 2007. There was and there still is this hope that a settled science will settle the politics and the economics of climate change, whereas in fact, some argue that it’s the other way round. In fact, I think this is a chicken and egg problem that can, in principle be debated forever. (The magic number of 100% consensus can never be reached; so both convergence and controversy will forever be what one may call ‘fractal’). But while this circular debate goes on at the top of science and politics, more bottom-up actions may be emerging based on a more popular consensus that might break that cycle and that might also bypass the tit-for-tat debate between those called by some warmists and those called by some deniers….

We’ll have to see whether the new (consensus-‘process’-based) IPCC report refuels the circular debate about the ‘scientific’ consensus; or whether it makes it possible to overcome obstacles to a ‘political’ consensus; or whether it provides impetus for more bottom-up actions; or even manages to join up all these elements. This would be surprising though, given the long-standing entrenchment of opposing discourses and the resulting political inertia. However, there are some indications that the polarisation in debate is breaking down in places, at least in the UK. Might there be some room for convergence rather than controversy after all?

This post is also linked to our ESRC project on climate change which tries to study long-term fluctuations in climate change debates

Added 25 August, 2013: Some articles and surveys on ‘consensus’ which are useful for gaining some insights into the current debate (thanks to @ChairmanAl and @etzpcm)

Survey of scientific opinion (2008)

Examining the scientific consensus on climate change (2010)

What else did the ’97% of scientists’ say? (Barry Woods) (2012)

Judith Curry consensus discussion (2013)

On the consensus (Shollenberger) (2013)

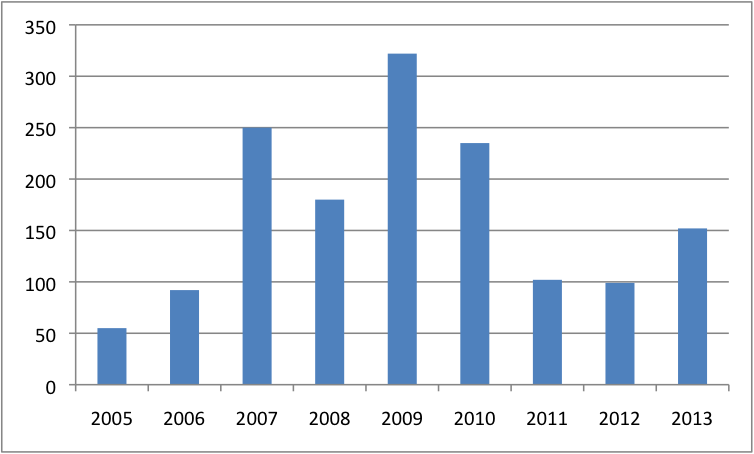

Addition, 08/02/2014: “No Consensus” (plus ‘climate change’) – Lexis Nexis – All English Language News (of course, ‘no consensus’ can be used in all sorts of contexts and in order to convey all sorts of meanings, but the peaks in 2007 and 2009 are still interesting, I think)

Image: Watercolour by James Gilchrist Swan (1818-1900) of the Klallam people of chief Chetzemoka (nicknamed ‘the Duke of York’), with one of Chetzemoka’s wives (nicknamed ‘Jenny Lind’) distributing potlatch at Port Townsend, Washington, USA, now in the Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale (Bibliographic Record Number 2003195) Wikimedia Commons

Considering Mann was one of the chief climategate protagonists (Mike’s Nature trick – Hide the decline), this has my irony meter jumping.

[…] provided a summary on the conference blog). All this made me think a bit more about the meaning of consensus. It seems to me that the word has (at least) two meanings and that these meanings were sometimes […]

[…] philosophical and sociological perspective. All this made me think a bit more about the meaning of consensus. It seems to me that the word has (at least) two meanings and that these meanings were sometimes […]