April 21, 2015, by Tony Hong

One store with different tales

By Dr. Xiaoling Zhang,

Head of the School of Contemporary Chinese Studies,

The University of Nottingham Ningbo China.

With China’s rise to a global power, we are seeing an increasing amount of literature predicting China’s future(s). It is safe to say that the next five years will witness more of this kind being churned out. The curious thing about this amount of predictions, be they journalistic or academic, is that although the CCP has announced quite a few years ago that ‘history proves that following blindly western political systems would lead China to a dead end and China’s current people’s congress system has strong vitality and great superiority’ (Hu Jintao, September 15, 2004, People’s Daily online), what dominates discussions on China’s futures in the West has been whether China will be a powerful authoritarian state or the world’s next liberal democratic country.

There is a recent realisation that what outsiders think China will turn into may be just wishful thinking. So observers are turning to what the Chinese, or different groups of Chinese, think of where China is heading next. All the future studies of China are, of course, due to the uncertainty of China’s future.

The China future studies have been multi-disciplinary, involving historians, economists, political scientists, sociologists, etc., through different lenses in trying to convince the readers that there is some certainty in the prediction of the uncertainty.

The foresting of China’s future(s) is inevitably closely related to the examination of the China Dream, because in unravelling the different versions of the China Dream, official and unofficial, we can tell, with more certainty, where Chins is likely to go, or so we are told. For instance, ‘China Dreams: China’s New Leadership and Future Impacts’ (2015, edited by Chih-Shian Liou & Arthur S Ding) discusses the agenda of China’s new leadership in their adaptation to political, economic, social, and global issues. Daniel Lynn, in his ‘China’s Futures: PRC elites debate economics, politics, and foreign policy’ (2015) examines and analyses Chinese leaders’ and other elite figures’ view. He frequently uses the neibu journal as a venue for the examination and analysis of discussions from authors who are likely to shape the future(s of China). William Callahan, in his ‘China Dreams, 20 Visions of the Future’ (2013), goes beyond the centralised view of the future to the emerging new voices coming from citizen intellectuals for the exploration of China’s futures.

It is widely recognised that to know China’s future one must study Chinese leaders’ speech and elites’ writing which may shape the direction of China. However, I am here proposing a new site – one that has thus far been overlooked – bookstores. I argue that Chinese bookstores are interesting places to explore because that is a place where different interest groups fight to get the attention of the customers – publishers, the propaganda departments at different levels, and the bookstores themselves. In other words, because bookstores have been commercialised, while they need to sell books that are required by the political climate, they also need to play to the taste of the clients. I therefore argue that examining what books are being sold in a city will often tell us what books are ‘required’ to be sold officially, and what books are in popular demand in that city.

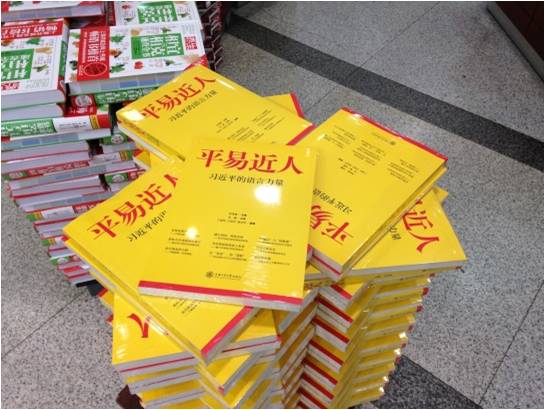

My visit to the Shanghai Bookcity in December 2014 reveals a lot about its service to the two masters: the state and the market. Meeting the eyes of the customers in the display window before they go in are books of three kinds: books on how to keep healthy, on travel, and exercise books of all kinds for children which are supposed to help them with their study. The ground floor is a mixture of everything: on the entrance of the ground floor is a designated area for materials on ‘CCP Central Committee Decision concerning Several Major Issues in Comprehensively Advancing Governance According to Law’. Sharing the most eye catching space on this floor are President Xi Jinping’s works, and books on how to keep healthy.

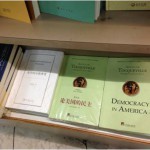

Taking into considerations the recent state decision on banning university textbooks which promote “western values”, it is amazing to see different versions of Tocqueville’s Democracy in America. One cover says – ‘a must read for citizens to understand the democratic system’.

I am not claiming that the biggest bookstore in Shanghai is representative of all bookstores in China. But surely, bookshops in a city do tell us a lot about what books are welcomed in that city. For the cosmopolitan city of Shanghai, one can see the challenge the state has set for itself in getting rid of the western values. One store can sell widely different stories.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply