February 29, 2020, by Peter Kirwan

As You Like It (RSC) @ Theatre Royal, Nottingham

The Bardathon made his RSC stage debut last night, in the small but pivotal role of ‘Tree Covered In Post-It Notes’. Brought on after the interval of As You Like It, this hapless audience member’s role was to stand in a coat festooned with hundreds of stick-on lines of poetry, and chip in with the occasional word while Celia (Sophie Khan Levy) reeled off Orlando’s fractured attempts at poetry. While I like to think I brought a bit of gravitas to the role without needing to go full method, it was a lovely opportunity to experience at first-hand the warmth and collegiality of the RSC touring ensemble on a night that was already highly unusual and demonstrated the embeddedness of the company’s commitment to an ensemble ethos.

First, the indisposition of Sophie Stanton led to Karina Jones, an actor with a visual impairment, stepping up to understudy as Jacques. When the current ensemble was announced, the RSC were rightly proud to be able to announce that they had cast its highest-ever number of Deaf or disabled actors (three) in a single company, though I expressed disappointment at the time that none were in lead roles. But when Charlotte Arrowsmith made headlines by being the first Deaf actor to understudy for a hearing actor during a performance of The Taming of the Shrew, reworking those scenes to integrate BSL, the company made an important statement about the embeddedness of its inclusivity practices, showing it had done and would keep doing the work, even when that involved reblocking scenes for a single night. And I was thrilled to see the same happening in this performance of As You Like It.

Jones’s integration as Jacques was so seamless that I didn’t realise she was understudying until late in the second half (and only then because I knew she had been meant to be playing Martext). This Jacques, in black shirt and trousers and red braces, was a solemn, sage presence, beautifully spoken and playing up Jacques’ melancholy reflectiveness. Jones’s disability means that she is accompanied on- and off-stage and doesn’t move excessively, especially when the set is cluttered with props or bodies, and the company has built this into her roles (in Measure for Measure, as the Mother Superior, Isabella supported her on- and off-stage). Here, Jacques took confident positions on the stage and the people of the forest oriented themselves around her, according her scenes an aura of unusual respect. For the moving ‘Seven Ages’ speech, Duke Senior (Antony Byrne) quietly bustled about the stage, feeding his troupe with stew from a pot, while they all listened reverentially to Jacques deliver a poignant version of the set-piece culminating in Jacques turning around to welcome Adam (Richard Clews) on ‘sans everything’. Similarly effective were Jacques’ final moments. Rather than Jacques bustling around the four newly married couples, she instead positioned herself centre-stage, and the four couples approached her in turn as if coming to seek for her blessing, letting her know they were there by squeezing her hands and she turning to them with love (or a warning of ‘Watch him!’ in relation to Touchstone and Audrey). And in a moment I found unbearably moving, the fact that Duke Senior embraced and then walked Jacques off-stage – rather than Jacques, as usual, walking out alone – underscored a warmth to the relationship between the two characters that was emphasised throughout via their physical contact. The small shifts in dynamic – the ways in which the other characters deferred to and acknowledged Jacques, the way she and Rosalind (Lucy Phelps) walked arm-in-arm while bantering, the calm kindness (sometimes with a bit of exasperation) with which she corrected others’ follies – turned this Jacques into a dignified, beloved figure, and I’m thrilled that I had a chance to see Jones in this role.

The company’s approach to integration was also evident in the ways that the ensemble built Clare Edwards, the BSL interpreter for this performance, into the show. It’s been a pleasure in recent years to see companies such as the RSC and Globe moving away from having BSL interpreters simply standing in a corner of the stage, but here Edwards’s agency within the production made it hard to imagine what it might look like without her. Circling the stage and taking up positions that helped her communicate the spatial and power relations between actors, as well as distinguishing her interpretation of different characters onstage, Edwards’s mobility and expressiveness integrated her into the business of scenes and allowed her to function fluidly as a character and bodily presence (‘It is not the fashion to see the ladies the epilogues’, Rosalind noted at the production’s end). Edwards’s work was particularly notable during the William/Audrey/Touchstone scenes. Audrey (Arrowsmith) was a Deaf character, and early in their courtship she and Touchstone (Sandy Grierson) drew comedy from their inability to interpret one another. Enter William (Tom Dawze), a hearing actor who became mediator between the two, while also harbouring his own love for Audrey. Edwards initially left the stage for Touchstone and Audrey’s first meeting (‘Where’s the signing lady gone?’ grumbled Touchstone), before returning to intercede, Edwards sometimes showing William how to sign better and the three BSL speakers laughing at Touchstone’s amateurish attempts to express himself. The interplay between these four performers was very funny, and Touchstone himself pointed out the extraordinary nature of seeing three actors performing in BSL (‘they’re like bloody buses’). Again, the care with which the production handled its onstage dynamics and the inclusion of actors with different needs and skills showcased a generosity which contributed to the presentation of the Forest of Arden as a space of joyful, kind solidarity and collaboration.

Sykes’s production distinguished clearly between the formal, brutal world of the court, and the relaxed, back-to-basics forest, visualised as a contrast between a stage-managed world of artifice and a backstage world of creativity. For the court, black curtains covered the upstage area and the raised gantry spanning the width of the stage acted as a viewing point for Byrne’s quite terrifying Duke Frederick, who stood proud and upright while the court sang an anthem on his behalf. Duke Frederick was a truly nasty piece of work: while he could appear genial when confident, and was happy to raise Orlando’s (David Ajao) hand in victory after he overthrew Charles the wrestler (Graeme Brookes), his violence was constantly brimming underneath. He had Oliver (Leo Wan) dangled by his ankle by Charles from the gantry (a quite spectacular bit of acting with genuine-seeming threat); he took off his tie and wrapped it around his knuckles as he threated to banish Rosalind; and when he stormed off after learning Orlando’s identity, he marched straight through the rope barriers that Le Beau (Emily Johnstone) had set up, leaving them sprawling across the floor in his wake.

There was still comedy within this world. Johnstone’s Le Beau was magnificent: an events planner on her last nerve, she twittered about the stage in suit dress and head mic, setting up the wrestling ring while also, in a great bit of physical comedy, repeatedly sinking into the plush green rug on stage with her high heels splaying out in different directions. But there was a serious underpinning, with Le Beau clearly terrified of Duke Frederick and thus displaying an anxiety which fuelled her interactions with the more privileged Rosalind, Celia and Touchstone. But Johnstone also drew a great deal of humour from her obvious thirst, especially for Orlando.

It was in this environment that the tensions of the lovers were set up. For Orlando, physically much more powerful than Oliver, his resentment towards his snivelling older brother was palpable, and almost manifested in violent action as the two tussled atop the swing on which Orlando was first discovered. Oliver’s conversation with Charles then felt like the comeuppance of a petulant bully, Charles even massaging Oliver’s shoulders as Wan sat, slumped, on the swing (a gesture of camaraderie which also made Charles’s deployment against Oliver at the Duke’s behest later all the more chilling). Brookes was a suitably intimidating Charles, initially wearing a suit before stripping down to shorts and loose top for the wrestling. In yet another oddity of this particular performance, Ajao seemed to be injured, and another actor (Aaron Thiara) ran on as the bout started wearing the same clothes as Orlando to wrestle in his place, another lovely example of the ensemble’s distributed skillset and collaborative play.

The playful relationship between Rosalind and Celia defied the severity of the court. Phelps’s expressive, joyful Rosalind enjoyed a close intimacy with Celia, played by Levy with an irreverent touch, especially in the character’s facial commentary of exasperation and amusement about Rosalind’s acts (which was especially important as Orlando and ‘Ganymede’ wooed later in the forest). The chemistry between Rosalind and Orlando was electric, the two leaning close together as Rosalind placed her chain around Orlando’s neck, and Rosalind’s exuberant presentation of herself to Orlando when she was ‘called back’ was matched by Orlando’s whoop in the air as he read Rosalind’s name on his chain. As the two met in the forest, their scenes were refreshingly played for romantic pleasure, though with a serious spin as Rosalind insisted they speak formal words of marriage in front of Celia, the two kneeling together, ‘marrying’, and then kissing longingly, before Orlando jumped up in surprise.

With the torture of Oliver moved to immediately after the discovery of Rosalind’s flight, the court and forest scenes were clearly separated, and marked by a spectacular transformation. Frederick was left alone onstage, when suddenly the black curtains were pulled down to reveal an enormous wooden disc hanging upstage. Racks of costumes were brought on, stagehands appeared to start shifting props around, and backstage calls could be heard over the tannoy calling the people of Arden to the stage. The cast entered and mingled, chatting with the audience, as everyone (including the BSL interpreter) switched into colourful, relaxed clothes. The austere world of the court was stripped away to reveal an unfinished, unpolished world full of rehearsal clothes and the apparatus of theatre. For much of the remainder of the production the house lights were up, and actors clicked their fingers to turn the lights up or down; it was a place of metatheatrical play.

The production’s energy shifted beautifully once in Arden. Audience members were brought up on stage to spell out Rosalind’s name, while Touchstone lounged downstage and harangued the audience for not laughing sufficiently at his jokes. Grierson was hilarious throughout, his dour, faded rock-star Touchstone both laconic and witty, whether improvising with the interpreter or performing a torch song illuminated by mirror balls. Jacques’ amusement at Touchstone’s antics played the two of them off against one another nicely, and he was also well paired with Patrick Brennan’s Corin, with their scene of philosophical argument getting increasingly rambunctious until it ended with Touchstone plunging a finger up Corin’s bum (leading to some lovely signed banter with the interpreter about how best to communicate what had happened).

The decision to play Silvius as Silvia (Amelia Donkor) was another unusual one, and again demonstrated this particular production’s interest in diversity (I struggle, in fact, to think when I’ve seen an RSC production develop a love relationship between two women before). Donkor was plain and unabashed as Silvia – a little hapless at times, but purely in love with Phoebe (Laura Elsworthy), a brash shepherdess in wool bikini and a self-possessed attitude. The three-way relationship with Ganymede was hilariously staged, with Phoebe unashamedly pushing up her breasts and crawling lasciviously across the floor towards Rosalind, while Rosalind gestured towards Phoebe while effectively asking Silvia ‘This? Really?’. But I was also struck by the rare exploration of a pansexual relationship here. Phoebe actively pursued someone who presented as male, but when she saw Rosalind in her wedding dress, she not only accepted her lot but more than happily accepted Silvia, a woman; gender was thus not the bar to Phoebe and Rosalind being married. This ending admitted of many interpretations; my sense is that the conclusion involved allowing everyone to be seen for who they were, and that Rosalind’s transformation revealed something about Silvia’s constancy.

And this ethos pervaded a production which seemed interested in honest, human feeling. Amiens (Johnstone) provided songs throughout, giving the forest a chilled out festival feel. I was especially struck by Byrne’s Duke Senior who moved about the woods with a kindness and care of those around him, whether serving them food or leading Jacques about, or calmly talking down the frenetic Orlando when he burst in on them, face covered and wielding a knife. The moment in which Adam began singing along with Amiens’ song around the pot of stew – showing the old man returning to health – was especially joyful.

It was in this atmosphere that the main romantic plots took place. Rosalind and Orlando’s wooing was playful and unproblematic, a collaborative venture that spanned teasing about the poems, coquettish roleplay, and laddish affection (Rosalind winced as Orlando punched her arm). Alongside this, Celia’s sighing exasperation with Rosalind was nicely paid off when she and Oliver instantly fell for one another, they bonding and staring into one another’s eyes even as they cradled Rosalind in her faint. Oliver’s transformation – he turning up in penitent clothes, open-hearted and open-faced as he freely told the women what he had done, marked an effective transition towards the final reconciliations.

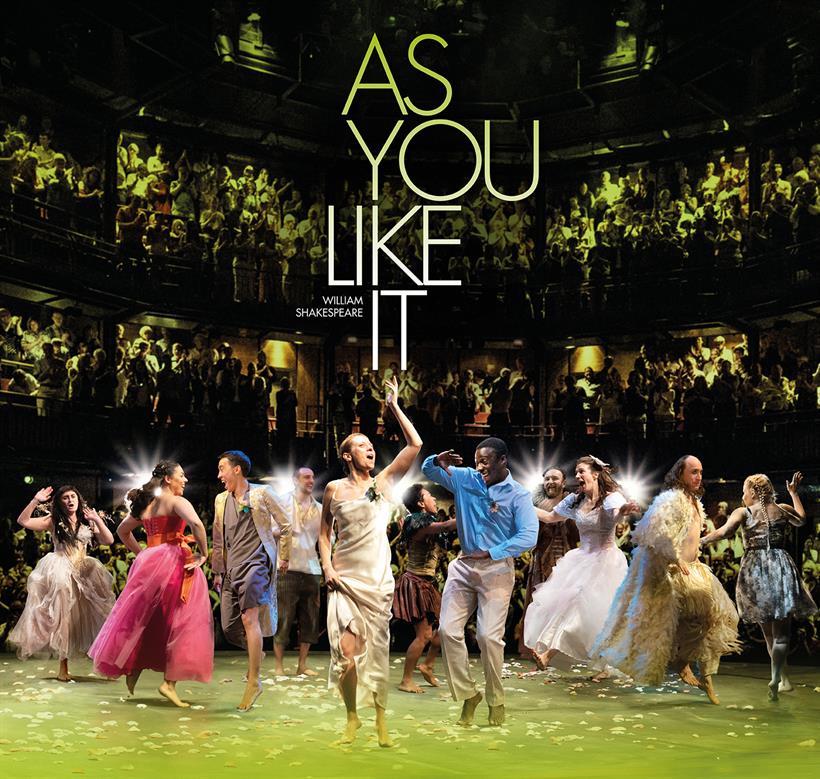

And this culminated in a spectacular conclusion as, in a relatively rare move for an As You Like It, Hymen emerged, a two-storey puppet of a god who was brought from upstage and who sat squarely at the heart of things, with a huge entrance built into his body to allow for Rosalind and Celia to be revealed in their wedding dresses. The puppet worked stunningly as an emblem of the company’s collaborative ethos, as five or six of them worked together to operate its arms, head and voice, and to gather the four happy couples together and bless them before sending everyone off in a dance, leaving Rosalind and the interpreter alone to thank the audience. The match-up of aesthetic and ethos, borne out in the extraordinary work done to share the mutual care amid the casting changes, made this an As You Like It to treasure.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply