February 29, 2020, by Peter Kirwan

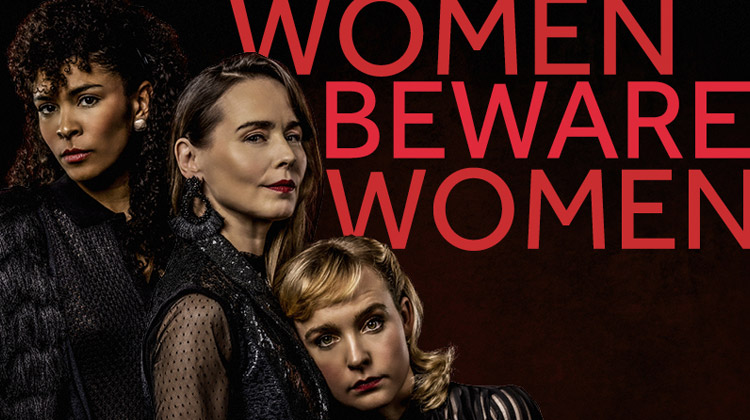

Women Beware Women (Shakespeare’s Globe) @ The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse

For a play of dark corners, shadowy deeds and masque-like spectacle, the Sam Wanamaker is surely the perfect playhouse. In Amy Hodge’s debut production for the Globe, and in collaboration with designer Joanna Scotcher, the SWP was darkened further than usual, with black tiling on floor and tiring house wall, and covers over the lanterns, evoking the moody, classy interiors of a luxury hotel, with gold finishings and elevator doors. The intimacy of the theatre forced the audience into the heart of the play’s abuses and double-dealings, creating an atmosphere of sordid complicity with no small amount of uncomfortable laughter.

Against the luxury trappings of the set, the quiet little world of Leantio (Paul Adeyefa) and his Mother (Stephanie Jacob) seemed very small indeed. Bringing Bianca (Thalissa Teixeira) through the audience and up onto the stage, Leantio’s presentation of his new wife to his dowdy mother, wearing floral dress and cardigan, was instantly unsuccessful. Bianca, in stockings and matching plaid jacket and skirt capturing the teen fashions of the vague mid-twentieth-century setting (think Heathers), was already underwhelmed, trying to be polite to her mother-in-law but already lingering and squirming over the thought of having abandoned all of her friends and connections for … this. Jacob, for her part, magnificently captured the clumsiness and fussiness of the Mother, getting a particularly big laugh for her enthusiasm for the chance to go to a banquet and take a doggy bag with her.

Right from the production’s start, then, this Women Beware Women foregrounded the desires and agency of women, and the ways in which men’s desires so presumptively trump them that the women’s needs often end up going unexpressed. The confidence with which Leantio brought home his new wife and then left her (albeit with some Romeo-style climbing of the tiring house wall to give her a parting kiss), and then attempted to reassert dominance when he returned home, was palpable. Upon learning the Duke had discovered Bianca, Leantio opened up a trapdoor that yawned like a grave as he told Bianca to close herself further up. Bianca – already having been raped by this point – was devastated by his reaction, and Teixeria sold Bianca’s distress at Leantio in a way I’ve never fully seen before. The production cut the bickering between Bianca and the Mother, which in the play shows Bianca asserting arrogance even before Leantio’s return, instead offering her as a traumatised victim who her husband then threatened to shut away. In this light, faced with a choice between a Duke offering her status, privilege, liberty and comfort, and a husband who offers her confinement rather than support, the production made crystal clear why Bianca would answer the Duke’s summons.

The world to which Bianca fled was lascivious and entitled. Livia (Tara Fitzgerald) held sway in her house, enjoying an intimate relationship with Guardiano (Gloria Onitiri) and lingering over the lines where she seems to show attraction to her brother Hippolito (Daon Broni). These three ran rings around their more staid brother Fabritio (Wil Johnson), but had more ambivalent levels of control in relation to one another. Fitzgerald played Livia as someone with dis/misplaced sexual energy, as in the lingering hands on her brother and her friend, and who especially relished the bits of power she had, as when she joined forces with Guardiano to make absolutely clear to the Mother that she would be staying to play a game of chess, a command the Mother only realised the seriousness of belatedly. Livia’s manipulation of Isabella (Olivia Vinall) was another moment where Fitzgerald’s performance relished the control she had over someone more vulnerable, as she milked the long backstory of Isabella’s ‘true’ father for all it was worth.

Hippolito, meanwhile, could barely restrain himself around Isabella, and the early scenes in which Isabella came frustrated to her uncle and threw herself into his arms were made unbearably creepy as Hippolito, unseen by her, traced her outlines with his hands, just avoiding touching her, but leaning in from behind as if about to overwhelm her. Isabella had a touch of Marilyn Monroe about her, all blonde curls and an innocence which seemed to be part of Hippolito’s attraction to her. But as Livia reminded her not to tell her uncle about the news, Isabella shifted in her seat, the idea planted, and when Hippolito entered she advanced on him purposely, sexually, finishing her lines perfectly with a lingering kiss. The pact between them sealed, Isabella’s quick decisions to marry the Ward and to enjoy her uncle privately ratcheted up the speed; again, though, this seemed less like a sudden switch to vice than a woman acting on the option that allowed her the most freedom, finally given some leeway.

Guardiano’s control was more industrious, especially in his oversight of the Ward (Helen Cripps) and Sordido (Rachael Spence). The casting of women in these three roles allowed the subplot to become an overt critique of stereotypes of toxic masculinity. The Ward and Sordido were public schoolboys, the Ward a spoiled brat used to a culture of entitled misogyny, and with no line between ‘banter’ and abuse. In one shocking sequence, Sordido sang a song about the physical qualities that women should have, using an extended mime of an invisible woman that was being appraised; in the middle of the song, the Ward got carried away and began brutally flogging the imagined woman with his badminton racket, everything crashing to a halt as he pummelled repeatedly at the empty space where the imagined woman lay. The dynamics were also clear in a fabulously staged, but very ugly, upskirting scene. Isabella was placed on a plinth and scrutinised and questioned. The Ward’s assumption of power as he leered at her established the power balance in one direction, while Isabella’s subversive asides and quick replies reclaimed some agency – before Sordido put on a pair of surgical gloves and shoved his finger up her skirts as Isabella squirmed, the brute physicality of the act an assertion of patriarchal dominance and casual misogyny.

Guardiano loomed around the edges of scenes like this, the enabler and approver of a culture of abuse of women that served his own interests. And in this, his role in the chess scene became important as, Bosola-like, he made everything happen. The chess scene was innovatively staged with the ensemble emerging and standing on either side of the stage carrying candlesticks in the shape of white or black chess pieces. As Livia and the Mother played, the pieces moved around the board, with Bianca and the Duke entering on their respective cues as Livia and the Mother slammed down the stopper on a chess clock. Guardiano escorted Bianca through the middle of this, and as the Duke (Simon Kunz) emerged from the audience and stepped onto the stage, the chess pieces all walked off and Guardiano slammed shut the central entrance, trapping Bianca with the Duke. The sequence that followed was distressing to watch, as the Duke leaned into her, told her not to struggle, and then slowly pulled down one of her stockings and began kissing her. Bianca froze into a position of fear as the Duke moved around her, kissed her, touched her, and then left the stage and Bianca collapsed. It was unbearable to watch, perhaps all the more so for what wasn’t shown; the symbolic power of the chess game and the representative gestures of the Duke and Bianca told more than enough.

From the Duke’s banquet on, everything became messier. The Duke’s banquet was a party fuelled by copious booze, during which the Mother sang and offered olives to the audience, Livia lusted thirstily after Leantio, and a still-nervous Bianca was gently ushered into high society by the Duke. Again, Bianca’s performance made clear here her fear – the Duke offered an ambivalent protection, and she was as scared of Leantio as anyone else. Hippolito and Isabella danced sexily; the Ward responded by playing a hornpipe on a snare drum while Sordido danced, smacking his drumsticks in the direction of Isabella. The score throughout was brilliant: a jazzy double bass underscored scenes of sexual interest, while Sordido and the Ward’s music was driven by a washboard; and discordant, minor key variants of the Wedding March repeatedly played. And Fitzgerald was hilarious as Livia awkwardly tried to sit next to Leantio, suddenly seeming to forget how to balance on heels, and cursing herself for her inability to manage her own affairs. The corruption of the play’s second half began blurring the lines significantly between different moral standpoints. To this end, it seemed significant that the Duke was played by the only white male actor, his authority trickling down to a corruption among everyone else that balanced images of lust and abuse across racial, gender and age barriers. In a court this sordid, everyone was grasping for power.

If there was a weak point of the production, it centered around Leantio’s death. Hippolito and Leantio’s fight was quick and brutal, Hippolito killing the younger man with a broken piece of glass stabbed over and over into his chest. But – whether because there was some textual truncation or whether they simply hadn’t let the fast-moving production breathe – the moment seemed to come with little preparation, ending Leantio’s story very quickly. And the fast-moving sequence in the aftermath of the murder, setting up all of the subsequent revenge plots, was difficult to follow. Most effective here was Livia’s grandstanding, unashamed announcement of her treachery in lying to Isabella, leaving the (by now) pregnant Isabella gasping in horror at her own swollen belly and trying to move away from the product of incest inside her.

Happily, the production pulled the threads back together for a beautifully clear and surprisingly textually faithful rendition of the masque, with the characters leaving behind modern dress to appear in togas and ornamental wings as the various mythological figures, while Bianca, Fabritio and the Duke joined the audience to watch. Everything here went off beautifully: Bianca’s plot was clearly signposted with a bright red cup containing the poison, that the masquers went out of their way to ensure went to the Cardinal (Jacob) when the Duke initially picked it up. Livia descended from the ceiling and choked and coughed all the way through her speech from the incense Isabella was allowing to drift up, but managed to pour her molten gold on Isabella before she died; and Guardiano spent ages trying to get Hippolito to stand on the trapdoor before walking backwards into the open trap – from which the Ward jumped up, bloodied and in horror at having stabbed his guardian, before running away. The whole was undercut hilariously by the Duke and Fabritio repeatedly turning to the audience and shouting that they had no idea what was going on, and the dramatic irony of the Duke walking in disbelief over to his brother and picking his undrunk red glass out of his hand to soothe his nerves was the cherry on top.

This production perfectly balanced the obvious comedy of the play with an ethical, rigorous attention to the impossible choices foisted upon the play’s women. The choice to stage moments of assault seriously and shockingly, without indulging in the exploitation of the actors’ bodies, was especially commendable, inviting empathy and horror without being gratuitous. The parodies of misogyny in characters such as the Ward were allowed to be funny while still being part and parcel of the same abusive structures that led to rape and murder; even Fabritio contributed in his roar to Isabella that she would marry a clearly unsuitable man. And the underlying critique of the privileges of the wealthy also cast a cynical edge on the economic aspect of the whole thing, in which a capitalist society forces women into the role of objects and possessions, whose sexuality is to be bartered as any other commodity. And as the Cardinal turned to the audience, the only person left alive on stage, and invited us to survey and interpret the bodies littered around the auditorium, it seemed to invite us to consider the ways in which we all enable that exploitation.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply