February 4, 2013, by Peter Kirwan

Candlemas Revels at Middle Temple Hall

As part of a quite wonderful conference this weekend, I went to Candlemas Revels at Middle Temple Hall on Saturday night. The preceding two-day conference, convened by Jackie Watson and Darren Royston, focused on the Elizabethan and Jacobean context of the Inns of Court in relation to the legal and social culture of early modern London, its influence on the literature and drama of the period, and the potential of the Inns as a space of performance, debate and the development of young people. During the festival a recurrent series of anecdotes occurred, taken from the reports of John Marston, John Manningham and others, adding anecdotal colour to the historical context.

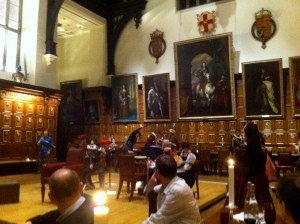

The Revels, a three-course banquet interspersed with performance, took these anecdotes as its basis and constructed a wonderfully rich sequential performance that lasted several hours and made full use of the spectacular Middle Temple environment (which, inevitably, I photographed liberally). Combining dramatisations of prominent figures from the Temple with recreations of masques presented to Queen Elizabeth and Queen Anna (including portions of George Chapman and Inigo Jones’s The Memorable Masque, which I reviewed a partial recreation of at the Shakespeare Institute two years ago), Royston and Watson created a spectacular, entertaining and extremely amusing evening.

The primary performers consisted of the Nonsuch Dancers, Royston’s own period dance troupe, and a troupe from Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance under the direction of Anne Daye, who performed the sequences from the 1613 Memorable Masque. This section included a torchlit procession of masquers, a stately but lively dance with Indian plumes offsetting plain white masks, and the highly comical antimasque of baboons (below). This very amusing playful dance, originally performed by the Children of the Queen’s Revels, saw six dancers in monkey masks engage in a range of acrobatics, mock accidents and simian behaviours, waving rudely at the audience and delighting Queen Anna (Frances Campbell) who sat enthroned on a dais. The layout of the spectacular Middle Temple Hall accentuated the presentational nature of the masque, the monkeys entering from afar and only partly approaching the throne, keeping a respectful distance.

The linking material set up some wonderful characters. Royston himself played John Marston, and Tomos Young the diarist John Manningham, who the others continually mocked for recording everything in his ever-present journal (an injoke for the historians). Steven Sparling took on the volatile and much-maligned John Davies, and Benedict Smith his victim Richard Martin in the infamous bastinado incident (bel0w), in which Davies entered the hall, approaching Martin, struck him over the head with a bastinado and then fled. An incident which had been reported repeatedly during the conference, this sequence brought the house down as, during the ensuing fracas, swords were drawn and the stately Temple reduced to a state something like farce.

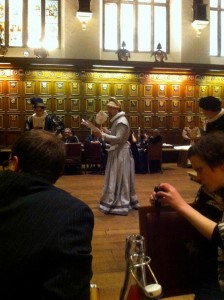

The reported anecdotes throughout saw the actor-dancers ‘ghosting’ rather than assaying their roles, standing in for their ‘characters’ as if, in effect, in a masque. This fitted the tone of the event and made a crucial distinction between the participatory culture of the revels and the professionalised performances of the theatre. The more choreographed performances were reserved for the dancers, elegant and precise. I lack a vocabulary for adequately describing early modern dance, and I defer to the image below.

A beautiful decision was made, however, to integrate a sense of the social significance of the dance into the performances, allowing the event to stand not just as a historical reconstruction but as an imagination of social performance. During one of the dances, the Queen descended to choose her partner, and selected Manningham. The descent of the Queen to the main floor brought with it a sense of heightened expectation, her slow movements and gentle smiles treading the fine balance between the retention of decorum and the delight in participating in the social engagement (crucially, of course, she touched her partners). As Manningham began showing interest in another of the female dancers, however, the Queen’s peace dissolved, and in utter silence, she turned and abandoned the hall, to the tears of her maidservants. Manningham’s disgrace saw him keep to the far end of the Hall for much of the ensuing evening. In instances such as this, the players invited us to experience the masque as a moment of vital socio-political importance, a dance of state in which minor decisions had potentially massive ramifications.

The squabbles of the Templars came out as they began rehearsing a scene from Marston’s Parasitaster, where the continuous heckling and insulting exchanged between the men was translated into performance. As much as I would like to recount the barbs and witticisms thrown between the actors, the three course dinner and wine were something of an obstacle to the memory of specific detail; however, the purpose of the playlet was to allow the disgruntled Davies to be taught a lesson. Manningham, dressed as a woman (a punishment for his earlier transgression?) took particular delight in the vengeance.

The Revels concluded with the audience joining in a series of simple Almains and country dances of which, happily, photographic evidence does not survive. The care taken, though, to incorporate the participatory nature of the revels into an event paid off in a communal experience, beautifully choreographed and scored, that acted as a memorable indication of how the building and its social conventions shaped and were shaped by the kinds of performance written for it. The easy interplay between ‘Templars’ and performers, and the constant utilisation of shared points of reference, demonstrated the potential of this environment for significant social progression, and hinted at the level of preparation and investment accorded these events.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply