February 5, 2013, by Peter Kirwan

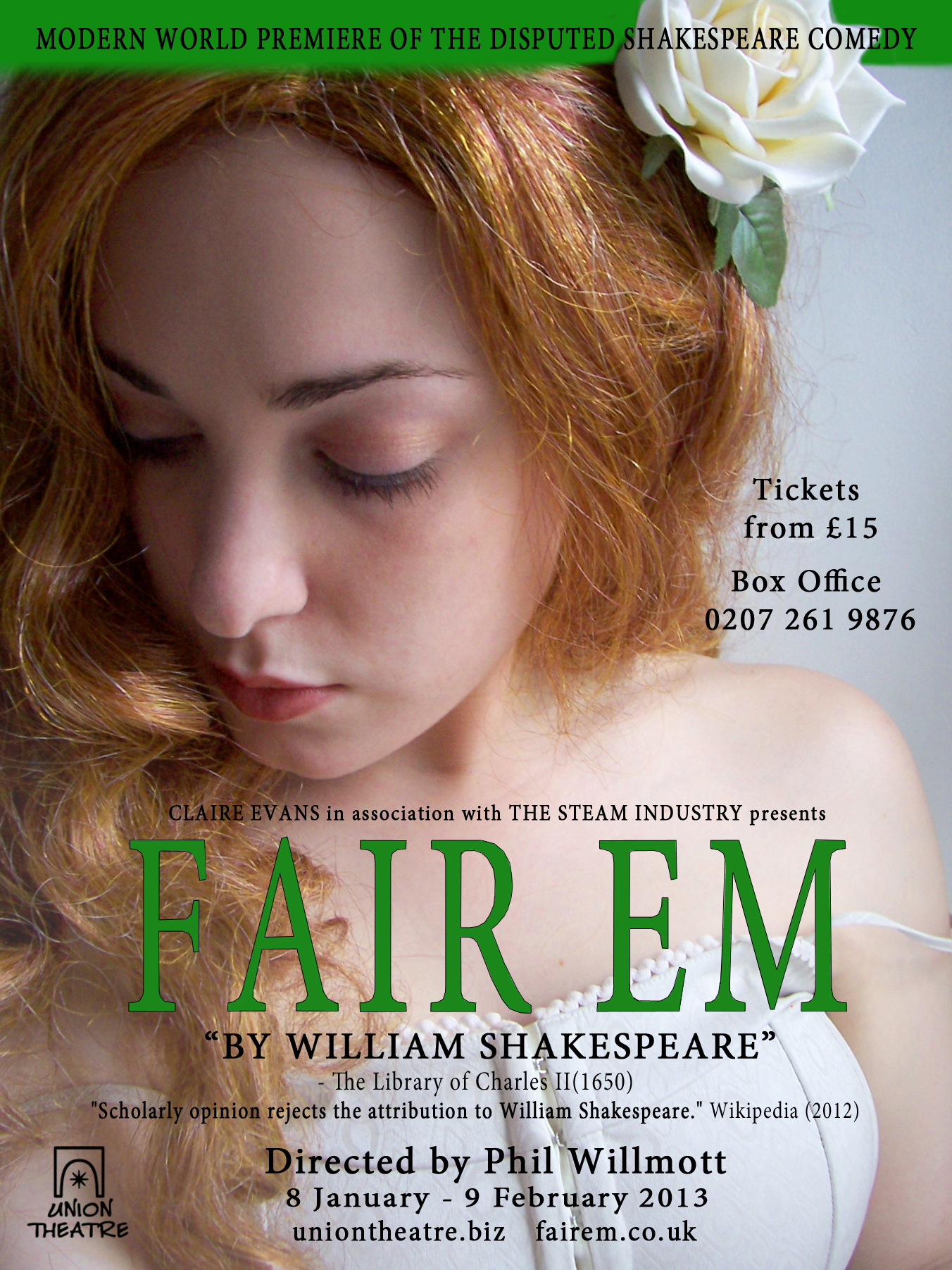

Fair Em (Steam Industry) @ The Union Theatre

Long-time readers will know that my scholarly research is based primarily on the group of anonymous or misattributed plays best known collectively as ‘The Shakespeare Apocrypha’, of which Fair Em is perhaps the most obscure, to scholars as well as theatregoers. Seemingly one never to shy away from a challenge, director Phil Willmott continued his run of fringe Shakespeare at the Union Theatre, following Double Falsehood and King John, with a game, lively production that combined nostalgia with a distinctly contemporary sensibility.

To get the academic disputes out of the way, the production notes are riddled with errors, even if these are understandable. Most significantly, my recent work has reminded the scholarly community that the play was first attributed to Shakespeare in a volume belonging to the library of Charles I, not Charles II, and this is a collection that contained a wide variety of plays, suggesting that the connection to Shakespeare is entirely opportunistic and based entirely on its 1631 publication date, rather than any real claim. Willmott instead defers to Wikipedia, but recent scholarship has attempted to attribute the play either to Robert Greene or Thomas Kyd. It’s perhaps a shame, as the negative press reviews this production has received harp continually on the unlikeness to Shakespeare, which simply isn’t the context in which Fair Em should be being critiqued.

The ‘main’ strand of the surprisingly even-handed dual plot follows the lovesick William the Conqueror, who is enticed to Denmark by a beautiful portrait only to find that the King’s daughter, Blanch, is not what he expected, and instead transfers his affections to Mariana, a lady at the Danish court beloved of his companion, Lubeck. Curiously, the portrait itself was not shown here, which made little sense of the opening conceit. While the source play allows for William’s change of heart to be fickleness rather than a statement against Blanch, here Willmott required Madeline Gould’s Blanch to present herself as repulsive to him through her (deliberately) tuneless singing and bolshy demeanour. The play as a result shifted to draw parallels with The Taming of the Shrew, Blanch imagined as a Kate-like figure whose aggression and forthrightness were tempered by the demure Mariana (Alys Metcalf), who engineered the body swap that sees William steal Blanch away thinking it to be her.

Jack Taylor’s William was tempestuous, a medieval warrior lover who was ultimately better pleased with a maid who could match his fire. The decision to have him share his initial disgust with the audience, and have the audience laugh with him at Blanch’s presentation of herself, aligned his and our view rather unfortunately, inviting us to share in the sense that a deceit was at work. While this worked towards a more modern agenda, a Disneyfied ‘It’s what’s inside that counts’, it took away from the equally interesting potential to explore the political dilemma offered by the visiting suitor who switches his advertised affections. Instead, the Denmark scenes took on a straightforwardly (but genuine) comic air, with Gordon Winter’s similarly cantankerous King of Denmark matching William for extravagant displays of masculinity and offering something approaching a genuine threat.

In the parallel plot, William’s deputies in England pursued a Miller’s daughter, the titular Em. Here, Willmott drew out some of the interesting inversions of standard early modern comic structures. Em was in love (albeit a rather chaste love) with Manville, played from the start as an arrogant dolt by David Ellis, who appealed to the audience to join in with his petulant scorn of his rivals and understand his jealousy, adopting a downstage viewpoint similar to that advanced by William when sharing his distaste for Blanch with the audience. Mountney (Tom McCarron) and Valingford (Robert Welling), the two other rivals, first engaged with Manville in a gloriously funny wooing sequence during which each attempted to place a gift centrestage for Em while singing to their unseen love. As each entered, they tossed away the other’s gift (forcing Valingford to scrabble desperately after a flying birdcage), resulting in a finely choreographed dance of desperation. Crucially, all three were presented as equally inept, causin Caroline Haines’s Em to instigate a plot to dissuade the unwelcome suitors through feigning deafness and blindness. During these sequences, Mountney and Valingford bewailed their ill fortune with woeful appeals to the audience, with Welling in particular grimacing almost to tears. Crucially, the hidden Manville also believed Em’s disability and disclaimed his own love, appealing again to the audience and storming out in high dudgeon. The audience was thus asked to empathise, not with Em’s choice of lover, but with the one suitor – Valingford – who was canny enough to realise that a trick was being played.

Across these two merry, farcical plots, Willmott and his team overlaid an atmosphere of medieval pastoral. Pantomimic backdrops displayed a sailboat moving from ‘England’ to ‘Denmark’, and the excellent onstage band, ‘Green Willow’ accompanied the action with songs, dances (including a wonderful first half closer which placed William at the centre of a rowdy masque) and Anna Sorensen Sargent’s lavish period costumes. The music was the production’s strength, underscoring the action throughout, but also its weakness. The combination of folk music that created a wistful nostalgia and jazzy numbers that built the energy was wonderful, but the music was often overlaid too intrusively, directing the audience’s emotions to an overly didactic and frustratingly reductive extent. This was most a problem during the sequences of Em’s feigned blindness and deafness, where the doo-wop vocals became intermingled with the actors’ lines and made it difficult to hear, let alone understand, the premise of Em’s trick. The production made the odd choice to have Em’s ‘deafness’ emerge partway through her scene with Mountney rather than from the beginning of their ‘interview’ (during which she never responds to anything he says), which went further to muting this effect.

I am less persuaded than this production was that Fair Em is simply a romp, but as a romp it worked well. Haines played Em as a straightforward and sharp heroine, careful of her father and kindly towards the suitors. The opening of the play staged the initial flight of Sir Thomas (James Horne) and his daughter, and the onstage band helped them change into peasant gear to Sir Thomas’s clear distress. The gentle humour of the pastoral situation kept the Manchester scenes friendly throughout, with Robert Donald working hard with a dull role to make the elderly clown Trotter a wistful presence, whether handing his urinal to an audience member or leering disconcertingly after his young mistress. Yet while the primary tone of these scenes was light, it did allow Em’s clear distress at Manville’s abandonment to gain emphasis.

Conversely, the debates in Denmark tended towards the edgy. While the production sensibly did not try to impose a modern psychology on what are essentially stock figures, the interactions during these scenes got to the nub of the plot’s issues. Tom Gordon-Gill’s Lubeck reacted angrily to the disguised William’s attempt to cut in during a masqued dance, which descended into a full-scale brawl with some pleasingly dirty fighting (including Blanch taking Mariana to task). It was the following scene, though, during which Lubeck had to express his anger while also showing deference to his king, that the play’s dramatic potential came through most strongly. While Lubeck doesn’t have the space to become a romantic lead, his brutal manhandling by Denmark and Mariana’s appealing wit in pursuing the disguise plot, did much to reorient the plot against William.

The use of music as an emotive cut throughout was understandable, as part of Willmott’s desire to ensure an audience could follow an unfamiliar play. This was coupled with narrations in the opening scenes that spelled it out, perhaps too far. Nonetheless, it served to cast the play within its own period as a minstrel piece, recited and scored by the band, and in communicating this lost gem to a modern audience, Willmott and his company succeeded in telling a clear and pointed story that communicated the farce with heart and zest.

The ending, however, was distinctly modern. Blanch, accepted by William in silence in the original play’s closing scene, was here given a decisive set piece speech that advocated Em’s right to choose her own husband, on the basis of which William finally saw Blanch’s quality.Willmott’s radical rewriting here was an anachronistic oversimplification of the play’s gender politics, and despite Gould’s convincing delivery of this Kate-like speech, it rather betrayed the implied intention of presenting the play on its own terms, troubling patriarchal structures and all. It is to the production’s credit that these adjustments didn’t seem out of place to the academic colleagues who I saw the play with, and I doubt I would have spotted it myself if I hadn’t been studying the play for so many years. In theatrical terms, the decision was a coup. By having Blanch step forward to become Em’s advocate, and emphasising Em’s own agency in choosing her future husband, the two disparate plots were tied together effectively and a clear arc created for the central heroines. It was a bold statement to close a confident production of an entertaining lost gem.

A shorter version of this review was published previously at Exeunt Magazine.

[…] arguably, the finest work by the much maligned Robert Greene, a historical romance in the vein of Fair Em and a fine example of the late sixteenth century stable of university conjurer dramas that also […]