April 28, 2022, by Peter Kirwan

Henry VI: Rebellion (RSC) @ The Royal Shakespeare Theatre

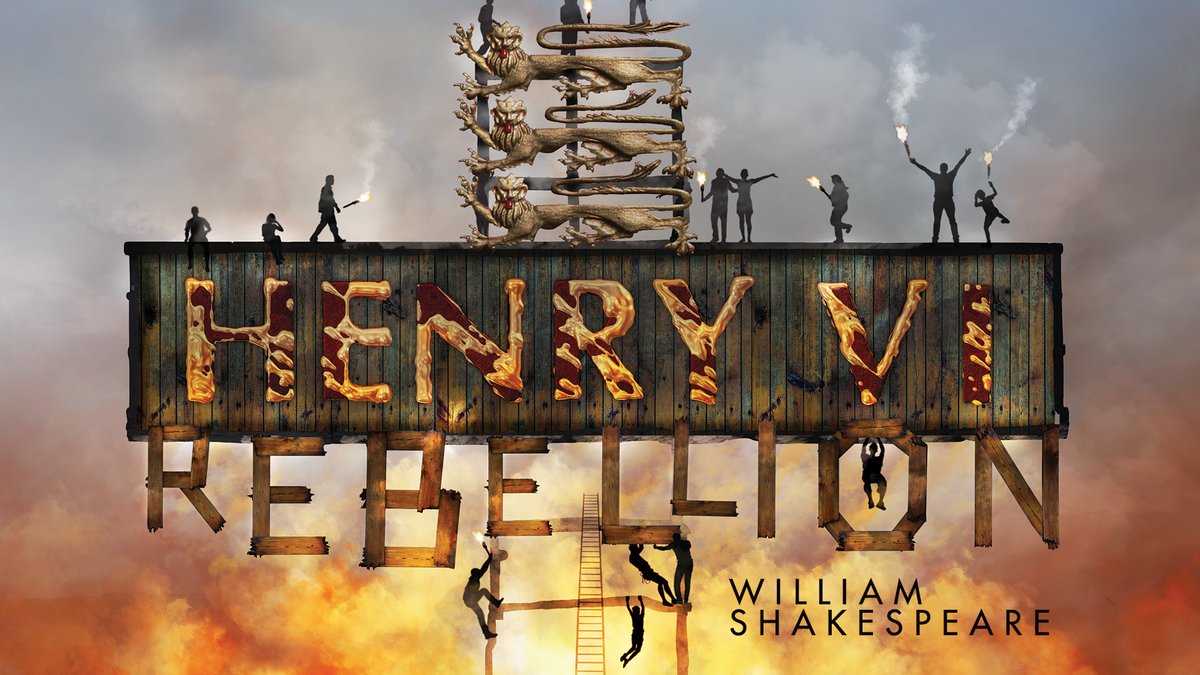

The unique problem facing any stand-alone production of Henry VI, Part 2 is the suspended ending. Other plays that are part of a sequence – 3 Henry VI, 1 Henry IV, for instance – still manage to reach a point of conclusion or at least pause; 2 Henry VI, by contrast, spends its running time setting up the board for the War of the Roses, winnowing down the potential antagonists, and finally unleashing the war, ending with the Yorkists in pursuit of King Henry. Owen Horsley’s new production for the RSC – following last year’s 1 Henry VI: Open Rehearsal Project – interestingly chose to restrict itself to only the first four acts of 2 Henry VI, denying audiences even their first sight of the future Richard III. Instead, the final lines were given to Mark Quartley’s King Henry VI: ‘Was ne’er subject longed to be a king / As I do long and wish to be a subject’.

By retitling 2 Henry VI as Rebellion, the production sought its unity in the exploration of the relationship between the nobility and the commons, allowing Quartley’s final lines to serve as a reflection on the double-edged nature of privilege. From the opening, as the nobles of England gathered around an over-sized banqueting table to toast the coronation of Queen Margaret (Minnie Gale), the commons gathered silently around, watching, implicitly judging in their drab costumes as the petty, careless nobles roared with laughter and enjoyed their riches. They left silently, but their presence was a harbinger of rebellion to come. Later, the line ‘Is this the government of Britain’s isle?’ drew audible snickers from the matinee audience; an elite ruling class heedless of the needs and interests of ordinary people resonating perhaps even more closely given recent developments in the UK.

By focusing only on the first four acts, the production was able to give relatively full treatment of the scenes featuring the common folk (in stark contrast to The Hollow Crown, which cut non-noble characters almost entirely). Perhaps surprisingly, though, the common folk – with the exception of Peter – were given relatively little dignity. Horner (Daniel J. Carver) was a drunken bore, sozzled by the time he got on stage as his mates fed him booze, while the apprentices (played by a group of Next Generation performers who rotated from performance to performance) cheered on Peter, who prevailed with a cudgel given him by Salisbury (Peter Moreton). Peter’s piety as he praised God was a stark contrast with the (understandably) comic sequence of Simpcox and his evangelical followers (this group played by a group of amateur players from Cornwall, as part of the RSC’s ‘Shakespeare Nation’ community project). The beggar feigning disability was given short shrift by Richard Cant’s Gloucester, suddenly discovering his legs and running away from the Beadle’s whip, while his followers ran after screaming ‘A miracle!’ The brief moment of Simpcox’s wife pleading their desperation – she holding back from the chaos and offering a sincere explanation – gave some weight to the moment.

The Jack Cade scenes, though, were played largely for comic value. With exaggerated Kentish accent, Aaron Sidwell’s Cade was a boastful, louche roarer, whose asides to the audience didn’t evince any particular self-awareness. Deprived of his death at the hands of Alexander Iden (which was a shame, as it felt like this would have allowed the implied political potential of these scenes to reach a point as York’s stooge met his rather more sober end), Cade came across as a more simply unserious and comic threat. For his final stand-off, he was introduced atop a parody of the Les Misérables barricade, using a large staff as a phallic prosthetic, and roaring at the crowds. But the build-up was to a more simple comic ‘come to your master’ sequence, as Buckingham and Clifford (Daniel Ward and Carver) on one side and Cade on the other called to the mass of rebels, who ran back and forth between them before finally choosing loyalty to the king.

The use of amateur actors to flesh out the company and play the rebels was a lovely touch, a meaningful piece of community-building, and the Cornish company were indistinguishable for the most part from the professional cast members. What was disappointing was that, in order to accommodate this, the production ended up being more cumbersome and overtly choreographed. The commons spoke in a single voice, the ensemble synchronised chorically, rather than allowed to be chaotic. And before the introduction of Cade’s mob, a bizarre ten-minute ‘interlude’ to allow for a very busy yet entirely pointless set change completely interrupted the momentum of the performance. It seemed a shame to make such a feature of the commons, to imply their significance, and then ultimately to underplay their potential for dignity and impact. The ease with which the common folk were swayed felt like an extension of the nobility’s own dismissal of them.

This was, otherwise, an efficient and well-told 2 Henry VI that kept things simple and concentrated on telling a clear story. Deprived of continuity with 1 Henry VI (only a couple of actors returned from last year’s rehearsal project), and lacking the final act, it felt like place-setting for a more through 3 Henry VI, but did a fine job of getting those pieces into place. Simple highlighting cut through the mass of characters to clarify points: heavy musical beats underscored York’s (Oliver Alvin-Wilson) soliloquies, identifying him as the figure to watch (and Alvin-Wilson was great in the role, sallow-eyed and firm in his speech, already a monarch in his mind). Quartley’s soliloquy at the end was similarly marked, and concluded with the reveal of York and his army waiting to take over. And a series of projections on the back walls highlighted the faces of the key players, illustrating the ever-changing faces of those who would rule.

The production’s first half was the strongest, with the assorted nobles back-biting and fighting for favour. Cant, as Gloucester, and Paola Dionisotti as Winchester, dominated much of the squabbling in the early scenes. Gloucester was irascible, constantly moving, and isolated from everyone else. He seemed pale next to Lucy Benjamin’s exaggerated Eleanor, who brazenly insisted on her place in the court and reacted with clearly unwise arrogance towards Margaret. Almost from the start, from the moment he realised that the Duchies of Anjou and Maine had been lost, Cant gave the impression of a man who knew his authority is coming to an end, and who was increasingly flailing against the inevitable; Eleanor had no such self-awareness (a fact exploited by Angelina Chudi’s Hume, who fawned over the Duchess but whose face quickly changed in her absence as she admitted her scheming). With Eleanor’s unwise actions damning both her and her husband, Dionisotti’s Winchester was able to sit calmly back, a smug scorn in her voice, as she choreographed Gloucester’s downfall. The suddenness of Winchester’s own fall was movingly done, Dionisotti unravelled and padding at her own palms, lost and wandering on the stage until finally laying down and dying. Gloucester’s appearance to lead his one-time enemy off the stage and to death was moving, though frustratingly stylistically inconsistent with anything else.

The other nobles’ stories came through efficiently, if not with any particular individualism. Warwick (Nicholas Karimi) was confident and vaunting, though rarely dominant; his father Salisbury (Peter Moreton) a solid and formidable presence, but both felt ready in potential rather than fully deployed. Benjamin Westerby’s Somerset was probably the most ill-served by the lack of connective tissue to 1 Henry VI; while Westerby gave a suitably silky performance, the character doesn’t have as much to do here. Ben Hall, on the other hand, had plenty to do as Suffolk, effectively Henry’s right-hand man, enjoying his brief period of sway. He also had one of the juiciest scenes when captured by the pirates, who descended on ropes from the ceiling to a background of crashing waves. Suffolk was entirely unafraid, revealing himself and announcing his identity in full confidence that the pirates would respect his status and leave him alone. The laughing pirates were unimpressed, but to his credit, Suffolk went to his (brutal and bloody) death unaware that he was ever truly at risk, in one of the production’s best indictments of the unquestioning privilege of the elite.

This was nicely continued into the Cade scenes. Cant returned as Lord Saye, shaking with his tremors as he tried to reason with the roaring rebels (Conor Glean was particularly good fun as Dick, with two butchers’ hooks and a constant gurning snarl). The dragging off of Lord Saye was one of the production’s more brutal moments, though the sympathy given to Saye made absolutely clear that the production had no sympathies with these rebels, however just some of their complaints may have been. An off-kilter choice to include some live onstage filming of Cade certainly added some visual variety, especially as the screens showed Cade and his troops marching around the foyer spaces outside the theatre, but – without a larger political purpose and no further integration into the production’s aesthetic – it seemed an odd choice.

Looking for a through-line was difficult, but it came from Gale and Quartley as the Queen and King. These two actors were the ones who carried the quieter, more reflective moments, and who were given privileged emotional responses. Gale was typically outstanding as Margaret. From the start she was confident, arrogant, revelling in her new position. She wasn’t cruel, as such, to her new husband, but certainly scornful of him, and unafraid to flaunt her relationship with Suffolk or to confront Henry when he refused to participate in the arrest of Gloucester. But it was after Suffolk’s death that she started to unravel and where the complexity of her character became truly apparent. She was never seen after this point without Suffolk’s head, which she cradled and rocked with, heedless of who saw or of how much grief she displayed. Yet she was still able to break away from it to tell Henry that she would die for him. Her undying loyalty to Henry and to Suffolk simultaneously seemed to be breaking her, and as much as this Margaret seemed invested in power, this was no detached pursuit of simple status, but an emotional arc.

And Henry was the innocent at the heart of all of this. Youthful-looking but always kingly, Quartley absolutely nailed his final speech, recalling how he was crowned at nine months’ old, and seeming like an old man even despite his youth. Throughout the production he grabbed onto moments of peace, hoping against hope for the sustained good humour of those brief pauses in the bickering. But as things collapsed, he was increasingly seen on the floor rather than on his throne, often sprawling, often contorting himself, often burying his head in his hands. He frequently put his hand to his head, as if the noise of the commons and of the nobility was drowning out his own inner voice. Rebellion, for this Henry, manifested as mental turmoil, as a slipping ability to hold onto his own identity. And with the final image setting up a direct conflict between Henry and York, with all other distractions removed, this inner conflict was teased as the focus of the upcoming sequel.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply