April 21, 2022, by Peter Kirwan

Much Ado About Nothing (RSC) @ BBC iPlayer

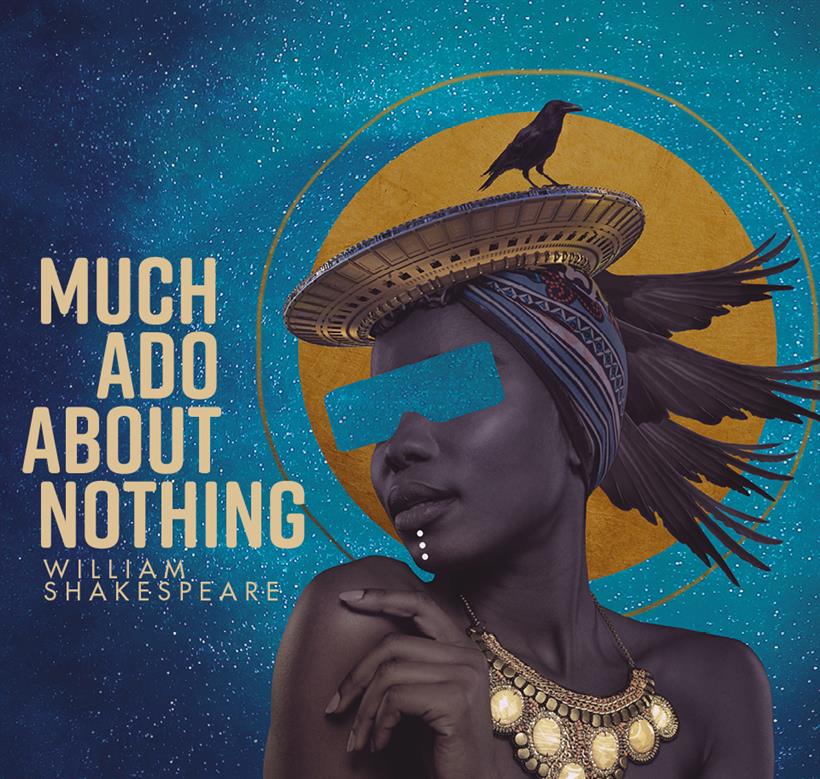

Roy Alexander Weise’s Much Ado about Nothing is a landmark RSC production in several respects. It’s the first full-scale main-stage production directed by a Black director at the RSC (in 2022!), and the first ‘repeat’ production to interrupt the RSC’s now eight-year project to stage the whole canon. The filmed version of the production also deviates from the traditional ‘Live From . . .’ format, with an extended post-production editing period allowing screen director Indra Bhose and his team to shift away from the raw theatricality and overt presence of the audience that typify the live cinema broadcasts in favour of a more processed sound design and dynamic visual edit, suitable for the BBC. And it’s a rare production of Shakespeare to be set in the future, with Jemima Robinson’s set design and Melissa Simon-Hartman’s costumes conjuring an afro-futurist fantasia for the post-Black Panther world.

The lavish design is the real star. Abstract artworks create a futurist garden of triangles and spheres on sticks, with oranges, yellows and greens dominating the visual field. The materials range from plastics and metals to straw and fur and beads, the different elements combining to create distinctive environments rooted in both past and future. But the real jaw-dropper is the costumes. From the elaborate, towering headpieces worn by Beatrice and Hero, to the contemporary Elizabethan chic of the masked ball, to the gorgeous robes worn by elders, costume works throughout the costume to create explicit senses both of the individual’s own status and personality, and of their role within the broader society. When the gold-clad household come together to celebrate Hero and Claudio’s wedding, the visual evocation of the community is surprisingly moving.

Messina is a bold, lively, egalitarian world. The wars of the opening are present – evoked by the arrival of Don Pedra’s troops doing a kind of ritual dance, and Pedra and her lieutenants descending from the ceiling – but are quickly put aside. Women and men both enjoy prominent roles in this society, and there’s a great emphasis on personal grooming and outward display; Claudio and Pedra mock Benedick while they’re all getting their hair done, a choice which emphasises that hair care and design is important for men as well as for women (indeed, it’s all Don John can do to get rid of Claudio’s barber). The greatest conflict in this society is between old and young, with Leonato (Kevin N. Golding) trying to escape the noisy music coming from his house, and taking refuge in conversation with Antonio. But this is also a proud society; with so much invested in public and social appearance, threats to image are taken seriously. Claudio (Mohammed Mansaray) is quickly provoked by ideas that he is being humiliated or disrespected, and his response to Don John of ‘If I see anything tonight why I should not marry her’ comes across strongly; the optics are all. This also underpins the tensions when Pedra and Claudio meet Leonato and Antonio in the street, the affronts to everyone’s dignity raw and bloody.

The society of this Messina is marked by ritual, ritual that is performed joyfully and collectively. The initial presentation of the newly wooed Hero to Claudio is announced by Toyin Ayedon-Alase‘s Don Pedra with a ritual cry, which brings forward the people of the household, holding their hands forward in a formal interlinked gesture, but everyone smiling fit to burst. The presentation of Hero to Claudio is accompanied by the exchange of glowing spheres among those present. It’s a beautiful little sequence, and one of several small rituals throughout the production. It does, however, mean that the action of the play feels more than usually choreographed, especially when combined with the extended musical sequences. There’s less room for spontaneity as the characters assemble and move in pre-planned ways, and a greater sense of the governing force of the authorities, which makes Don John’s (Micah Balfour) night-time planning feel even more desperate. Some urgency is given to the more intimate moments by unusually close-up camera work, especially in the production’s opening scenes, that focuses tightly on the reactions and emotional responses of characters, picking out moments of individual experience within the community scenes.

This ritual erupts into celebration. Femi Temowo’s soulful music drives the production, in a style that suits the more produced feel of the filming. Khai Shaw’s Balthasar has several songs, accompanied by horns, drums and bass, and creates lush settings for the overhearing scene and for the wedding. But music is also key to everyone’s participation in this world, from the individual dance displays that pervade the ball, to Don Pedra’s emceeing, to Benedick’s own somewhat flat attempts to express his feelings for Beatrice in song. Song and dance, for this production, is the language that signifies belonging to a community, and its role here isn’t to shame or isolate, but to bring everyone together and to mitigate the formality and lavishness of the costume. It’s notable that, when things go wrong, the soundtrack goes silent; a lack of music in this world signifies problems.

By contrast to the ritual scenes, the moments of intimacy feel more natural. Beatrice, Hero and Margaret dressing together for the wedding is a particularly entertaining scene, the three women switching between attitudes and accents as they engage in their own merry war of words. The intimacy between Black women is taken as a matter of course, and is all the more powerful for the contrast of the ‘backstage’ women with the relative formality of their public ritual appearances. This makes the breakdown of the wedding particularly compelling. The blocking of this scene is a little odd, with the betrothed couple being positioned on a plinth facing away from the on-stage audience. But when Claudio takes over the platform to castigate Hero, all of the decorum falls apart. Hero (Taya Ming) comes into her own here, so used to knowing how things are meant to go that she has no idea how to respond to the unexpected; she shakes her hands, she shouts, she sways; this is not how things are meant to go. Her collapse feels like the only inevitable response.

The choice in the filmed version of the production to deprioritise the audience, both in the choice of camera angles and in the audio mix, sometimes means that the comedy falls a little flat; Luke Wilson’s Benedick, in particular, often feels like he’s talking into a void, his jokes and reactions lacking the response that completes them and presenting him as a more insular character. It creates an unusual imbalance, in that the scenes which are usually the absolute stand-out of Much Ado – the two overhearing scenes – here don’t really work. These are the most ‘traditionally’ directed scenes, with no background music and minimal use of technical effects, focusing simply on the actors’ placement in the space. But Benedick’s extended routine hiding behind his servant feels muted in all respects. The choreography is bland, with Benedick simply positioning himself behind his hapless servant. Benedick himself is very quiet, and rarely given visual prominence by the camera. And there’s almost no audible reaction from the audience to the attempts at comedy, or any energy to the audience-stage dynamic, which makes the mugging of Leonato and Claudio feel isolated; in Beatrice’s overhearing scene, it feels especially weird to see Akiya Henry’s Beatrice crawling across the stage while manipulating a wheelbarrow that’s covering her, yet for there to be no audible reaction from the audience. By contrast, quieter moments when the audience can’t help but be heard are still very funny: the moment when the page elegantly stands and pats Benedick wordlessly, sympathetically on the shoulder before gliding out; or Benedick’s high-energy solo on ‘There’s a double meaning to that!’ as he runs around the audience. From these moments, the implication is that it’s the filming, rather than the production, that is muting the dynamic.

Conversely, the Watch scenes – which largely feature more of the stage, and which depend more on back and forth between the actors – retain more of their comedy. Dogberry (Karen Henthorn) and company are dressed like rejects from Tron, with neon lines and basket-like headpieces, and their multi-coloured uniforms disperse the monolithic authority of the police. Dogberry’s deliberate reluctance to get involved in any actual policing is overt here, with she and Verges (Aryna Jalloh) standing next to a blackboard and flat-out instructing the rest of the Watch not to do anything; which makes the Watch members’ quick action to apprehend the drunken, louche Borachio all the more surprising. For all the Watch’s ridiculousness, there’s something natural about their interactions which makes them an endearingly chaotic element in this carefully choreographed world. When they do engage in their version of the formal ‘upstairs’ society, it’s parodic, with Verges and Dogberry wearing PVC judges’ robes and tube-based wigs, leaving Michael Joel Bartelle’s Sexton – wearing a suit of armour, unusually – to cut through the silliness with the profound news of Hero’s death.

One decision which backfires somewhat is the re-gendering of Don Pedro as Don Pedra. Ayedon-Alase is excellent in the role, especially in her full-throated emceeing of the first big party scene, and having a woman as the most powerful person on the stage is an important reminder of the rebalancing of gender roles that often characterises the afro-futurist imaginary. This does, however, jar with the misogyny that underpins Hero’s treatment in the play, and is a useful illustration of what Nora Williams refers to as ‘incomplete dramaturgy’. It mutes the potential for seeing the isolation and judgement of Hero as part of a broader structural problem, stripping Pedra and Claudio’s (and Leonato’s) willingness to believe the worst of Hero of its social context. And perhaps more troubling, it means that Beatrice’s rejection of Don Pedra – when Pedra approaches her and offers herself as a substitute spouse – plays as a comedy ‘no homo’ moment, as Beatrice laughs nervously at rejecting the confident bisexual woman (who later flirts with Balthasar). To evoke queerness only to reject it (‘Princess – get thee married!’ says Benedick at the end, rather than ‘get thee a wife’) with a laugh feels like a disappointing vision of the future, even if it’s great to see that representation.

Within such a visually rich production, the traditional highlights of Much Ado about Nothing – Beatrice and Benedick – get a little lost. But Henry and Wilson are charismatic and funny. Their meeting following Hero’s rejection at the wedding is earnest and vulnerable, with Benedick in particular trying to break through Beatrice’s reserve. Henry’s Beatrice throughout is pre-emptively defensive, prone to hiding behind voices and attitudes and sardonic turns of phrase in order to prevent anyone getting too close to her. It makes her the life of the party, but it keeps her at a deliberate distance; and when Hero is undone, it’s easy to see why, as it seems hard for her to make herself vulnerable. Beatrice’s wit is protective, and when her defences come down, her anger is palpable. This also means that Benedick’s U-turn from saying he would never kill Claudio to agreeing to do so is much more clear than is usual – Benedick’s respectful, calm reception of her fury counters her rage, the two seeing just how important the position of the other is, and the two make a compact. The choice of the filming to fade out at the end of this scene – rather than show us the actors leaving the stage – brings a metaphorical curtain down on their connection, giving it greater emphasis. Benedick’s subsequent dignity when confronting the riled-up Pedra and Claudio is striking. Wilson stands upright, slightly hunched forward, resigned to what he must do, his hands folded behind his back, as he sets out slowly and clearly to the hot-headed Claudio what will pass between them.

The production comes together in its concluding half-hour by returning to ritual – but now, not the planned celebratory rituals of marriage and victory, but the more reluctant rituals of penance, trial, and forgiveness. In many ways, these are the production’s strongest scenes, precisely because the characters are now no longer dancing to a tune they already know, but are instead reacting to the unprecedented. I write this just after Steve Baker, a conservative MP, stood up in the House of Commons to call for the resignation of the Prime Minister, while also asking the Commons to recognise the gravity of such a call, and to approach any such displacement of a sitting prime minister with reverence and awe. The function of Dogberry and co. in providing some levity during these moments is more important than ever, because the leads are now deathly serious. The emergence of the shrouded mourners singing a lament to Hero takes the formal musicality of the celebration scenes and turns it to sober purpose, the weight of the scene visibly overwhelming Claudio, whose ability to speak a formal apology is hopelessly inadequate next to the beauty of Hero’s other mourners, placing him in a position receptive to grace. And in the final taking of a masked wife, ritual is used finally to mock and discombobulate a Claudio who is now able to take the humiliation, bear Hero’s anger, and kneel before her for forgiveness.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply