February 27, 2022, by Peter Kirwan

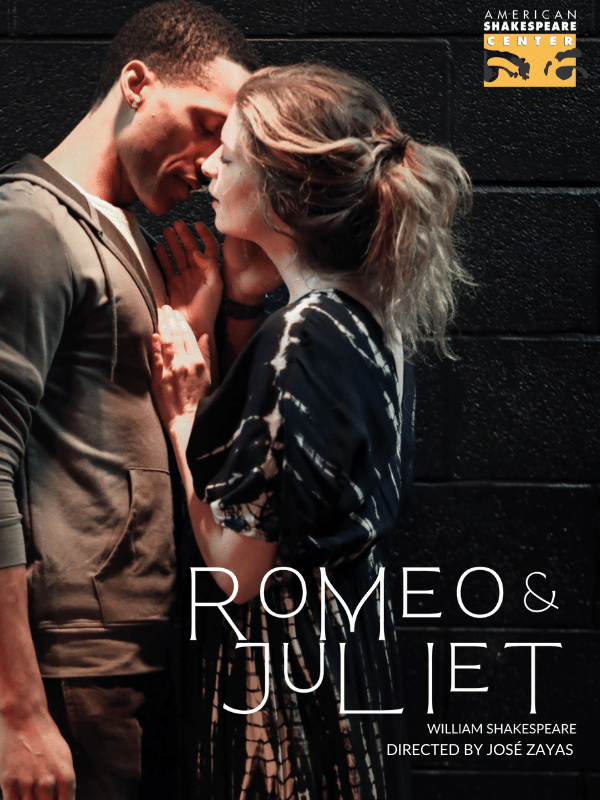

Romeo and Juliet (American Shakespeare Center) @ The Blackfriars Playhouse

This review is of a preview production, and may not reflect the production as of press night.

In January 2022, Brandon Carter became the third artistic director of the American Shakespeare Center, and the first to be a core part of the acting company. As such, while he has already carried several major roles (including a celebrated Hal/Henry in a sequence of the Henriad) for the company, his appearance in one of the title roles of Romeo and Juliet perhaps now carries additional weight. It’s an unusual role for an actor-artistic director, given the relatively ensemble nature of the play, but that’s perhaps what makes it such a strong fit for the ASC as the company gets back to its core business after the turbulence of the last two years.

As ever at the ASC, the pre-show gig set the tone, with the ensemble smashing their way through covers of thematically related tracks by My Chemical Romance (‘Teenagers’), Lil Nas X (‘That’s What I Want’) and Kim Wilde (a raucous ‘Kids in America’). But it was when Carter and Meg Rodgers (Juliet) came out to join the rest of the company and duet on ‘Love on the Brain’ that the production’s focus became clear. Carter and Rodgers’s steamy duet, sung deep into one another’s eyes where the rest of the tracks had been aimed at the audience, clearly demarcated these two from the rest of the cast, and allowed a joyful lust to take centre stage.

Interestingly, José Zayas’s production took two stylistically very different approaches to each half of the play. The first half was a frantic set of comings and goings, concluding with the banishment of Romeo. With barely a breath as the final song of the pre-show set ended, the Montagues and Capulets were in a full brawl, the entire build-up cut. With no stage-sitters on the stage, the cast used the whole space to set up beatings and team-ups and injuries, with some blood splashing around, and almost no ability to tell the difference between the two families (the perennial red/blue colour-coding was present, but subtle). Rather than clearly distinguishing Montagues from Capulets, this production instead looked with the Prince’s (Tevin Davis) eyes, seeing just a mass of violence, against which Romeo for one tried to define himself.

The fast comings and goings of the first half felt very much like Romeo’s story, with the wiry Carter covering a huge amount of stage space, especially as he ran around the edges of the Capulets’ party. In a neat touch, this party saw the cast dress up in Renaissance costume and perform formal dances, while Tybalt (Sam Saint Ours) grudgingly led the band. The masked Romeo was an odd man out at this dance, and instead weaved in and around the dancers, sometimes knocking into them, sometimes getting grabbed by someone else, but just enough times managing to get into sync with the object of his interest – Juliet. The whirlwind dance scene set up the connection between the two through looks and the stolen moments where they were temporarily able to ignore the other dancers and separate themselves.

If Romeo was doing the legwork, Juliet brought the thirst (along with Erica Cruz Hernández as the Nurse, who had an unusually two-way flirtation with Patrick Earl’s Mercutio that went surprisingly far, leaving the flustered Nurse winking to the audience with a ‘Still got it!’). Rodgers’s beautifully expressive performance imagined Juliet as a strong-willed, independently minded and very frank young woman, whose hungry sigh of ‘You kiss by the book’ brought down the house. Earlier, we had seen her tease her Nurse with shared language and reminders of earlier times the same stories had been told, while telling her mother (Jessika D. Williams) quite clearly that she wasn’t looking to marry. Now, she took an active role in the wooing. The balcony scene – played on the very solid structure at the Blackfriars – saw her risking life and limb as she sat cross-legged on the edge, leaning down to her lover even as the substantial and high balcony kept her well out of his reach. Rodgers managed the scene beautifully, flitting between anger and frustration (a roared ‘BY AND BY’ was very funny), confidence, and laughter at Romeo, but rarely taking her eyes off him. Carter, for his part, had Romeo looking up, sincere, all openness, but far away.

The production didn’t try to situate these illicit lovers in a specific socio-political moment, but the resonances were hard to ignore. With the young fighters wearing street clothes and wielding knives, the offstage sirens that announced the arrival of authorities suggested a potentially even more terrifying threat which always seemed to unite the Capulets and Montagues in mutual interest as they fled the police. Further, while the casting avoided painting the feud in general as rooted in racial difference (both families were cast to be racially diverse), at least one moment rang with significance as the white Tybalt scornfully called the Black Romeo ‘Boy’ before attacking him. Romeo, for his part, seemed to know that waiting for the police would do him no good.

This led into the radically different second half. While the first half had played with the usual stage space of the Blackfriars and had particularly emphasised the fast changeovers as actors ran on- and off-stage, for the second half, the ensemble of twelve stayed almost entirely onstage. The interval set – which included a powerful group cover of ‘Only the Good Die Young’ and Rodgers’s belted-out rendition of Cat Ridgeway’s ‘Giving You Up’ – concluded with a dazzling performance by Carter of Martin Sexton’s ‘Can’t Stop Thinking About You’. Here, as so often with the ASC, the line between interval performer and role was blurred to meaninglessness, Carter/Romeo holding forth with a bluesy torch song accompanied by Chris Bellinger’s sax solo and an insistent double bass line. It was a stunning performance, which then went on to orient the whole second half around itself.

Following his song, Romeo went and slumped in the discovery space, hood pulled up, cradling himself in his grief. For the action that followed, the band – including the dead Tybalt and Mercutio – continued to pluck out the underscore of ‘Can’t Stop Thinking About You’, interestingly centering Romeo’s experience even as Juliet heard the news of Tybalt’s death. Throughout this second half, the band continued to evoke the basic riffs of the song, while the rest of the acting company sat on the edges and jumped immediately into the action as needed. By shifting the stage traffic from the physical comings and goings of Verona to a more psychically oriented series of connections between music, actors/characters, and the wider society, the production became much more intimate and much more inward-looking. Romeo no longer sought out an apothecary; instead, three band members held out vials of poison for him and he grabbed one. The Nurse, when she knocked to be let into Friar Lawrence’s (Gregory Jon Phelps) cell, had no spatial location for him – he simply looked out into the abyss of the audience, the knock seeming to be as much within his own headspace and fears as emerging from a locatable door. And with Romeo constantly visible, the effects of his actions on the rest of Verona could never be forgotten.

The increased visibility of Romeo in the second half risked unbalancing the production somewhat in his favour; however, Rodgers’s Juliet asserted herself in multiple ways, with some of the play’s more interesting staging choices. While much of the play was trimmed (including, unusually, ‘A plague on both your houses’), the scenes featuring Paris (Andreá Bellamore) were largely retained, enabling Paris to become an object of displaced fear and aggression for both Juliet and Romeo; indeed, it was Lady Capulet (constantly with wine glass in hand, a decision which now feels unavoidable in productions) proposing Paris, rather than the aggression of Capulet, that prompted the strongest reaction in Juliet. Juliet framed her pre-potion speech explicitly as a choice between suicide or the Friar’s plan, laying out the dagger and the potion in front of her, and pausing long before making her choice. Paris, meanwhile, gave Romeo a clear adversary, though interestingly he fought and killed her before Juliet was brought into the tomb on her bier, allowing for an unusual parallelism as Romeo dragged Paris downstage, walking in the same direction as Juliet’s funeral procession, alongside them.

While a pacey Romeo and Juliet is always welcome, the particular speed of the ending risked muting the effect a little. Carter’s moving dying speech as Romeo had him lying on the bier next to her, slowly lowering herself to die at her side. When Juliet awoke, however, she didn’t speak at all, seeing him almost immediately and immediately realising what had happened. Yet while her part was cut down at this point, Rodgers achieved something rare, with a decision I’ve never before seen in Romeo and Juliet – she didn’t actually seem to want to kill herself. For all she sucked at the bottle of poison and shouted at the heavens, when it came to trying to stick the dagger in herself, she quailed and quaked, and for the first time ever, I genuinely thought that she might not do it. Instead, finally, she screamed – a horrible, piercing shout of rage – before plunging the knife into her stomach. And after she recovered from the initial shock, a smile spread over her face, and she leaned down and wriggled her head painstakingly through a gap in Romeo’s arms, choosing her resting place, in a genuinely moving choice.

The sheer speed of this Romeo and Juliet meant some inevitable sacrifices, including some of the plot lines (Sydney E. Crutcher’s Balthazar in particular felt like an afterthought) and some of the more pointed political commentary that the production only had time to gesture at. But what the production achieved – especially in its stylistic shift between the two halves – was a shift from the social to the personal. Romeo’s love for Juliet emerged from a boyish culture of playing and intimate physicality (Mercutio and Corrie Green’s Benvolio were key to this), represented by his frenetic comings and goings, while Juliet hungered to break out of her balcony prison and literally get her leg over Romeo (poor Friar Laurence had to work hard to insert his Bible in between the two for long enough to marry them). But following the social rites of marriage and death, the production’s shift to the personal took us inside Romeo and Juliet’s trauma, and their desperation for their pain to be recognised. I wish I could return after the production’s had a few more performances to bed in, but it’s an auspicious start to the ASC’s new beginning.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply