October 25, 2021, by Peter Kirwan

Hamlet @ The Young Vic

Over the pandemic, most of us have had to get used to being apart from one another. I may be speaking for myself, but it’s been exhausting (if rewarding) to re-learn how to socialise, how to physically interact with others. Negotiating awkwardness and new boundaries is part of this, as well as remembering the social cues of reaction. If most of my conversations have been on Zoom or Teams, limiting my responses to my facial expressions or some text replies, then what does that mean for my physical vocabulary of gesture and response?

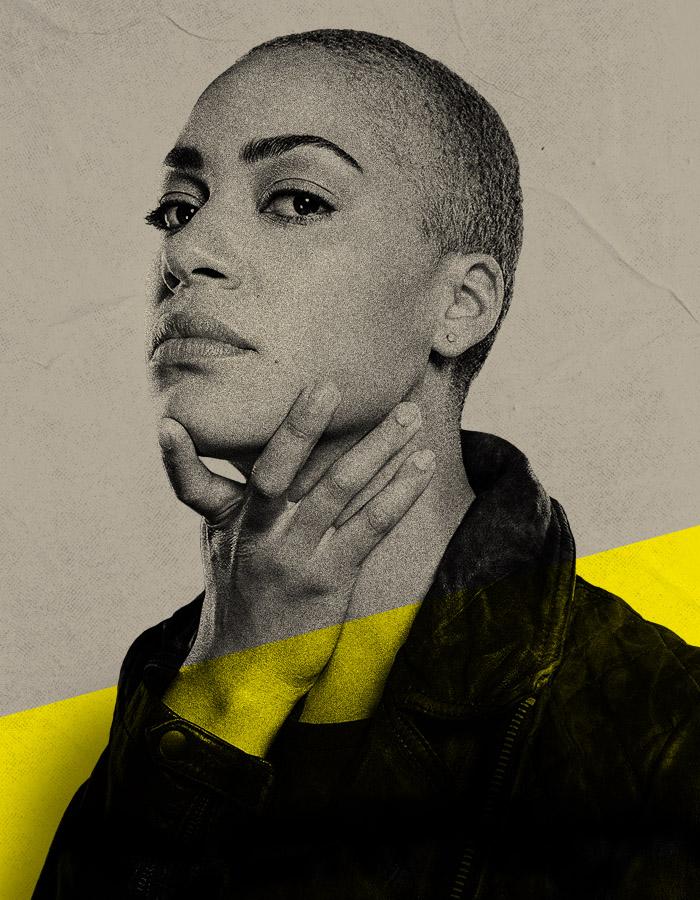

The most frustrating aspect of Greg Hersov’s long-delayed Hamlet for the Young Vic is its static-ness. For all the excitement of the casting announcement – Cush Jumbo as the first woman of colour to play Hamlet on a major UK stage – this deeply conservative production felt at times like a series of monologues. With a couple of honourable exceptions, actors tended to freeze in place except when they were actually speaking, both turning the stage action into an endless series of tableaux and also removing a sense of liveness from the events. Rather than reacting to what was happening in front of them, the cast appeared to be simply marking time until their next line or explicit cue. Particularly when watching scenes of quite extraordinary challenging of social mores – Ophelia’s (Norah Lopez Holden) screams during her madness, Laertes (Jonathan Ajayi) throwing himself onto Ophelia’s coffin – one might expect that those watching would do something, and the contrast between the passivity of the ensemble on stage and the emotional outpourings of whoever was speaking felt deeply awkward.

That’s not to say the production was a failure, but it struggled to make a case for itself. Anna Fleischle’s set aimed for a fusion of the historical (massive flagstones making up the floor and archway) and ultra modern (three rectangular blocks with a metal sheen, in which could be seen shadows and movements). The costume established the now-standard contemporary surveillance state: a faux-casual Claudius (Adrian Dunbar) and formally presented Gertrude (Tara Fitzgerald) backed up by armed bodyguard (Adesuwa Oni) and a series of attendants. In Dunbar, at least, Claudius’s impression of geniality felt well-earned; keeping his natural Belfast accent (slightly muted), Dunbar was convincingly disarming when talking Laertes down from his rage or attempting to soothe Hamlet. The scale of the threat that Claudius offered was less firmly established; this Claudius certainly wasn’t afraid to make the difficult choices to consolidate his power, but Dunbar’s performance never captured quite what drove this particular iteration of the usurper.

Motivation felt more generally lacking. The key performance here was, inevitably, that of Jumbo herself, who was always compelling even if she sometimes seemed to be acting in a vacuum (interestingly, ‘To be or not to be’ was decoupled from the nunnery scene, which came after the arrival of the players, though this weirdly separated the set-up for the eavesdropping from its realisation in ways that felt structurally unsound). With a confident drawl of disdain, this Hamlet was clearly pissed off at the world, and little gestures of defiance and disregard marked him as an unsettling presence. Jumbo’s compelling performance had very little to work off, though, leaving Hamlet angry at a world that wasn’t really doing very much. The appearance of the Ghost (a stilted Dunbar) against a background of raging flames was a surprising decision, but this was the only time the Ghost actually appeared onstage (between this and the Windsor Hamlet, what is it with Ghosts not bothering to come back after the interval?), and whatever prompted the hellfire was not followed up on. Further, Hamlet’s feigned madness was downplayed, emerging instead as an extension of the sullen, passive aggressive pre-emptive defence that characterised the performance throughout; yet the apparent diffidence of this young Hamlet was belied by his maturity in, for instance, his first confrontation with Laertes, during which he didn’t raise his hands to the angry brother of the deceased, and actually managed to de-escalate the situation. Jumbo’s reading of Hamlet felt coherent unto itself as a moody lashing out of grief at an unjust world, but it didn’t for me latch onto what was happening in the wider world of the production.

From an interpretive point of view, most effort went into the distinction between older and younger generations. Joseph Marcell was born to play Polonius The youth of the play were presented (not entirely flatteringly) as younger millennial/Gen-Z types, with Laertes in particular going for an interesting delivery of his lines as flat, throwaway prose, the taciturn reserve of the somewhat embarrassed older brother later giving way to more heightened anger following Ophelia’s death. Rosencrantz (Taz Skylar) and Guildenstern (Joana Borja) were classic students, taking self-indulgent selfies as they marvelled at finding themselves in the court (in one of two choices that felt like rip-offs of the Simon Godwin RSC production). Rosencrantz in particular was amusing as he blow clouds of smoke, fist-bumped Claudius, and shuffled and shambled about the stage with a deadbeat energy, becoming increasingly petulant towards Hamlet. Guildenstern, on the other hand, had one of the production’s most affecting moments in a beautifully delivered ‘pipe’ scene, in which Hamlet showed absolute ruthlessness in tearing a clearly devastated Guildenstern apart, leaving Rosencrantz to gently pull away his girlfriend from where she stood, nearly in tears, as Hamlet ended their friendship. Later, the final duel was turned into a knife-fight that seemed to me to uncomfortably co-opt urban youth violence into an aestheticised sport, which again had very little to do with the surrounding mise-en-scene.

Hamlet’s closer friends were more positively portrayed. Horatio (Jonathan Livingstone) seemed confused at everything going on around him; his long hesitation before he managed to pluck up courage to speak to the Ghost was a nice touch, and elsewhere he fumbled around in Hamlet’s wake. Ophelia was more dynamic, and nicely in control of her life, calling out her brother and then sharing a sign of victory with him behind their father’s back as Polonius (Joseph Marcell) handed over a credit card. There’s always a gimmick for Ophelia, and this one’s was music, with an early sequence of Ophelia and Hamlet dancing together during their courting as Ophelia listened to music on her headphones; this fuelled her sung set-piece as she stamped her feet in her madness at Claudius. More effective was her laying out the herbs of remembrance on a garment of her father’s, turning the giving of herbs into a memorial for her father. The funeral scene was one of the better sequences, with the Gravedigger (Leo Wringer) a Caribbean man singing Bob Marley (the other rip-off from the Godwin production) and setting up one of the funniest Yorick scenes I’ve seen for some time, as Hamlet choreographed the skull as an independently spirited ventriloquist’s dummy.

Ultimately this felt like a Hamlet without a purpose. For all Jumbo worked hard, the production was stripped of politics, lacked a sense of interplay, and created a world for which the stakes felt very, very low. It’s a production which had a disrupted gestation, and perhaps rehearsals were limited according to COVID; it certainly felt like the lead actor was part of a considerably more developed production than everyone else. As a fully realised Hamlet, aside from the historical significance of the casting, it’s hard even a couple of days later to make a case for why it matters.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply