August 19, 2021, by Peter Kirwan

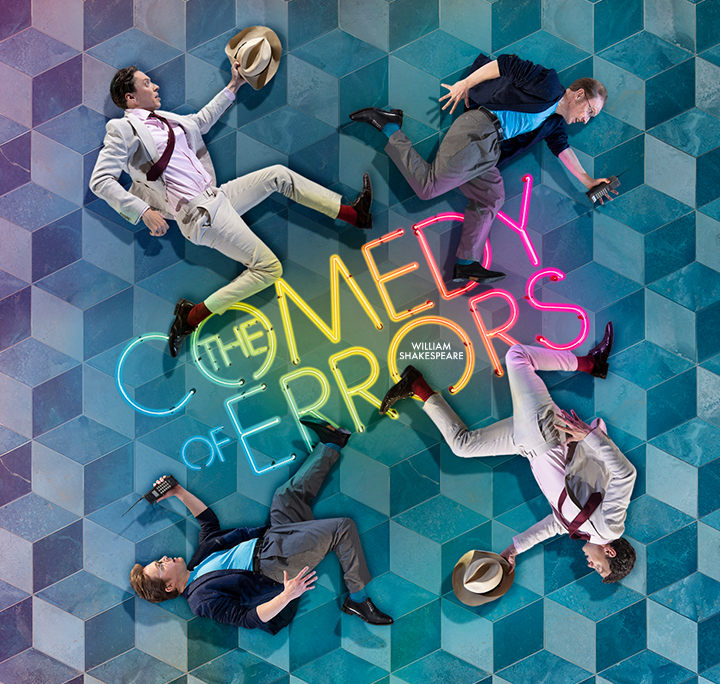

The Comedy of Errors (RSC) @ The Lydia & Manfred Gorvy Garden Theatre

‘Capitalism!’ crooned the four-strong Chorus who provided an acapella doo-wop score for Phillip Breen’s Comedy of Errors. Errors isn’t a play which demands a subtle approach, and the singers identifying the core interpretive ethos of this production offered a nice punchline, as on-the-nose as the punches that repeatedly landed on both Dromios’ faces. In a play which traces the exchanges (successful and aborted) of any number of objects, and which turns on the acquisition of goods and money that enable passage through the world of Ephesus, making Errors so explicitly a play about what we value made for an interesting interpretive touch.

This 1980s-set production took as its location an undisclosed location on the Arabian peninsula, in the throes of Western-oriented brash capitalism. Specifically, much of the action was oriented around a brand-spanking new luxury hotel, whose ribbon-cutting ceremony – with enormous ribbon spread across the walls of the RSC’s new outdoor theatre – acted as a setpiece for the second half. In this world, Middle Eastern businessmen welcomed Kevin-Keegan-permed footballers and celebrities with arms full of shopping bags into their spaces, while local hagglers met new Western arrivals off the boat. With the TV cameras on stand-by and a reputation as the new destination resort to uphold, the locals of Ephesus seemed desperate to be putting their best foot forward for their visitors – but the chaos caused by those visitors was to disrupt any decorous presentation.

It’s easy to see why this setting appealed to Breen and the company, but played to and for an almost entirely white (at least at this matinee) performance, it jarred badly. Right from the start, the production indulged in stereotypes of the Arabian peninsula: dictatorial leaders who order military guards to execute prisoners with a curved sword; fawning market sellers looking suspiciously around as they attempt to get money or goods from the tourists; corrupt businesses. And with so much of the location seen from the point of view of the new arrivals, the locals of Ephesus were continually othered by the characters who had the most privilege of direct address with the audience. It’s possible that the idea was to set up this point of view in order to mock it – after all, it was the white, Western-coded characters who were the ones who made spectacles of themselves through their violence and outbursts, disturbing the peace of the locals – but this reading never felt foregrounded enough to feel conscious.

What it did allow was a production that went an unusual way to skewering privilege. In Ephesus, Antipholus (Rowan Polanski) and Adrianna (Hedydd Dylan) led a life of luxury that also left them deeply unhappy. The heavily pregnant Adrianna allowed the production to indulge in more unpleasant tropes, this time of the angry and unreasonable pregnant woman, who resorted immediately to public outbursts. Her first encounter with Antipholus of Syracuse (Guy Lewis) took place in a nice restaurant, with the locals first politely ignoring and then openly staring as Adrianna roared at a silently bemused Antipholus. Earlier, she had taken off her heels in rage to attack her husband’s servant, Dromio (Greg Haiste), and throughout the production everyone cowered when she erupted into – quite understandable, actually – fury. The tired trope aside, Dylan did some more sensitive work as an aggrieved and quite lonely woman. She shared yoga sessions (overseen by the guru Dr Pinch (Alfred Clay) with her sister, Luciana (Avita Jay), who assumed some quite extraordinary poses that Adrianna didn’t try to match. But what Dylan communicated was a sense of helplessness and isolation – trapped in a posh hotel with no-one else to talk to, ignored by a husband who was roaming the town and having affairs, and worried that her pregnancy – she cradled her belly while asking if she had become ugly with age – had caused her husband to lose interest in her. Adrianna lived in a situation where she could have anything in terms of consumer goods, but the thing she valued most was denied to her, perhaps explaining her enthusiasm when Antipholus of Syracuse finally gave up and agreed to snog her.

Antipholus of Ephesus, meanwhile, was more unpleasant than I think I’ve ever seen. Turning up at his own front door with Angelo (Baker Mukasa) and Balthasar (Patrick Osborne) in tow, he was a swaggering, smarmy playboy, all brash confidence and immediate outrage when things didn’t go his way. This was a man for whom capitalism offers easy access to anything – power, goods, women – as signified by the card he confidently swiped to be let into his flat. When he was denied entry, his immediate turn to how he could use his money to get revenge – by going to the Courtesan (Sarah Seggari, an excellent understudy at this performance) and buying her trinkets – said a lot about the kind of power he wielded in this society. His punishment, throughout the production, was to be deprived of his access to money and goods, and to be shocked at how little sway he had once he no longer had currency. By his standout, post-breakout monologue in the final scene, with rope around his hands and a bloodied face, a frenzied snarl and a manic energy, he represented the flipside of an economy in which having is predicated on others not having.

Antipholus of Ephesus was contrasted with his Syracusan twin, a milder, more incredulous man. Where Antipholus of Ephesus participated easily and freely in the economic transactions of Ephesus, Antipholus of Syracuse was scared of them, repeatedly turning to (what felt coded as racist) worries about witchcraft and devilry in the merchants and tradespeople surrounding him. Yet he couldn’t refuse to participate in this exchange economy. He gave himself up helplessly to Adrianna (and had lipstick on his face for much of the rest of the production), and later appeared festooned with shopping bags and gifts (including a knife set which he and his Dromio, Jonathan Broadbent, hilariously unpacked to defend themselves when needed) that had been piled upon him. The setting offered one reading of this as the innocent tourist corrupted by the mercantilism of a foreign country; more fairly, though, this seemed like an indictment of an all-consuming financial system that consumes and/or destroys all who attempt to live within it.

If the Antipholuses were clearly distinguished, so too were the Dromios. Dromio of Syracuse was a confident, ambling man, ready with a prepared jibe and a dry observation. His relationship with Antipholus was amiable, underlined by the shock felt by Antipholus when, exasperated, he first struck Dromio of Ephesus and then his own man – at the moment of striking, the production paused and let the moment land while Antipholus looked horrified at what he had done. By contrast, Dromio of Ephesus was more than used to being beaten. This Dromio wore clothes slightly too big for him, and Haiste spluttered, his jokes coming out tinged with anger and regret. He was abject in a way Dromio of Syracuse wasn’t, made clear when he grabbed a microphone to finally unleash a tirade of historical abuse at his master for the years of abuse he had received (I was reminded here of Patricia Akhimie’s great work on corporal punishment in the play in Shakespeare and the Cultivation of Difference). This visible difference between the two made the ending, in which the two Dromios came together and Dromio of Syracuse removed a remaining piece of rope from around his brother’s hand before the two embraced, all the more moving, suggesting that – having found one another – that one Dromio might be able to help the other heal.

Microphones became the most important prop (both real and mimed) throughout a play in which characters repeatedly try desperately to make themselves heard. While all the actors were miked up throughout for audibility (which had the unfortunate effect of somewhat flattening the tonal variety), on-stage microphones were used to create complex soundscapes of authority and interjection. The tone was set throughout by the onstage musicians, who participated as costumed actors while singing a range of acapella music (created by Cheek by Jowl’s longstanding composer Paddy Cunneen) into their handheld microphones. But microphones also existed within the diegesis of the play as a tool of power. Dromio of Ephesus grabbed one to excoriate his master; Dromio of Syracuse took one up to perform his fatphobic setpiece about Nell (NB: for all that Broadbent appealed to the audience to forgive the 400-year-old jokes, this really was another case of the show having its cake and eating it; the raucous laughter at the jokes about girth acknowledged a skilful performance of the set-piece, but continued to validate the premise that fat people are there to be laughed at). Solinus (Nicholas Prasad) took up a microphone when he needed his citizens to acknowledge his command, and Egeon (a dignified Antony Bunsee) spoke his backstory into one while the singers accompanied him and two actors with teddy bears mimed the key motions of the shipwreck, giving his story the sadness and gravitas it merits. At the ribbon-cutting ceremony for the hotel, Antipholus of Ephesus tried to be dignified at a podium with microphone while Angelo harangued him increasingly angrily from the sidelines, even talking directly to the news crew there to film the event as he struggled to get through to Antipholus. And in the fracas of the finale, the hilarious Officer (Riad Richie) got out his siren-wailing megaphone to finally shut up the chaotic townsfolk.

These plays for attention spoke to a world in which getting one’s voice heard was almost impossible. Even Solinus, in a moving performance, was bound by his own rules, his voice becoming quiet as he acknowledged his inability to save Egeon after having condemned him, despite his obvious pity for him. Adrianna’s desperate attempts to get the Duke to listen to her at the end saw her fighting for physical space as she kneeled before him, but she and everyone else continued to struggle to be heard above the multitude of conflicting voices. Again, the competing noises of capitalism – with everyone claiming their own grievance in their loss of property and/or capital – meant that it was hard to redress any one individual complaint. Breen made good use of soliloquy to allow different characters to come to the fore – the Courtesan had a confident tete-a-tete with the audience in which she showed how she was going to assert her own rights, for instance – but for all of the individually expressed plans, the grievances of this society could only be resolved collectively.

This made the ensemble approach of the production even more important, and pleasingly, the characterisation of the secondary characters was consistently hilarious. From simple background jokes such as the grumpy footballer (Osborne) who was deeply unimpressed at being given a massive pair of gold scissors to cut the ribbon, and the confused local diner whose chair Dromio nicked, to more elaborate jokes, there was a depth to the physical comedy that felt lived in. Osborne was a consistent highlight. He played a waiter when Antipholus and Dromio of Syracuse had their first argument, but as he served them, his toupee suddenly flapped down, revealing his bald head, and sparking the long disquisition on hair with which Dromio and Antipholus mocked their waiter while re-establishing their own friendship. Elsewhere, other minor characters were fleshed out. The Second Merchant (William Grint) was a Deaf Russian mobster with a massive bodyguard/translator, who pulled out knuckledusters and a gun to intimidate Angelo into getting his money, and who grabbed the unclaimed cash at the production’s end before marching out. Richie’s Constable had a long extended tussle with Antipholus of Ephesus which saw him sitting on his captive, holding his legs like a wheelbarrow, and getting increasingly exhausted, before being poked in the eye by another interloper. And Clay’s Dr Pinch, with his gold Y-fronts and his woo music from leading the yoga sessions, stepped forward as peacemaker to bring Antipholus to heal, before throwing aside all peaceful intentions after Antipholus smacked him in the face.

The production staged a fear of others that at times felt xenophobic, but at other times captured the more pervasive fears of COVID-19. Antipholus of Syracuse obsessively squirted hand sanitiser onto himself every time a local touched him, scrubbing his hands desperately; later, as Adrianna seduced him, he prematurely spurted a large volume of it into the sky, and later still he cast it at the Courtesan as if warding away spirits with holy water. Aemilia (Zoe Lambert), meanwhile, emerged from her convent wearing a mask and gloves and barred entry to what looked like a hospice as much as a cloister, snapping her mask back onto her face when she wanted to end a conversation (incidentally, her authoritative voice was one of the few able to cut through the din). But to take the most positive spin of the production’s interpretation, this Errors seemed to be setting up the fear of others in the hope that this fear could be overcome. It didn’t entirely allow for forgiveness – while Antipholus of Ephesus tried to tenderly stroke Adrianna’s pregnant belly, Adrianna wasn’t having any of it – but as the two Dromios slowly came together and embraced, the production captured something of the desire to be together again, to touch – perhaps even to be back in a shared theatre. The Lydia & Manfred Gorvy Garden Theatre may be a temporary space, but in this production and with this ensemble, it became a place to share again the experience of finding one another. It may have had its flaws, and some pacing issues, but in its replacement of the values of capitalism with the values of interpersonal connection and human solidarity, this Errors aimed to set the world right.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply