January 3, 2021, by Peter Kirwan

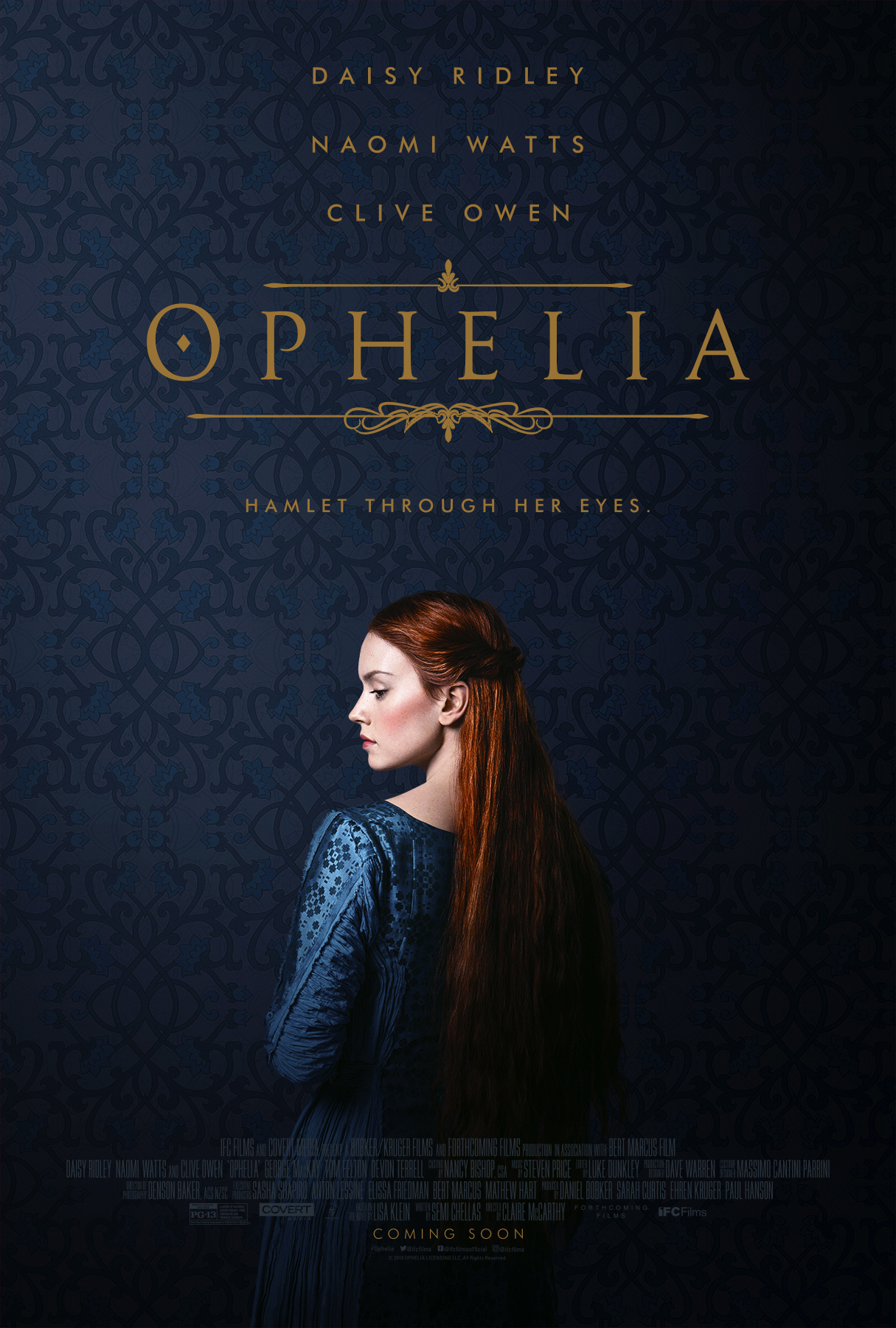

Ophelia (Covert Media) (DVD)

John Everett Millais’s ‘Ophelia’ is a defining pre-Raphaelite work, and a profound interpretive influence on Hamlet, on stage and on screen. It’s the starting point for Claire McCarthy’s film of the same name, as Daisy Ridley’s Ophelia spreads her arms and flowers in a lake and slowly sinks beneath the water. The painting renders Ophelia passive, a victim, a portrait of female beauty in death that aestheticises her at the climax of her violent treatment. For McCarthy and screenwriter Semi Chellas, working from Lisa Klein’s novel, however, this is a defining moment of active, not passive, resistance, from a woman working with whatever means she can to change her fate and the fates of those around her.

Ophelia is one in a long line of retellings of Hamlet from Ophelia’s point of view; I’ve written myself about Paul Griffiths’s let me tell you, and there’s a whole book dedicated to Ophelia’s afterlives across media. This one is rare as a decently budgeted, large-scale film version that is able to take the medievalist aesthetic of period-set film versions of Hamlet such as Zeffirelli’s and apply it to a self-consciously feminist reclamation of a play whose male-centred viewpoints are usually so entrenched. At the same time, the film draws on YA and historical romance tropes to rework Hamlet as a combination of love story and political intrigue. It doesn’t always work, but it’s a smart retelling of the play that offers intriguing reworkings of key moments, hueing close enough to the narrative that it functions as a version of Hamlet while also boldly striking out in its own direction when it deems it necessary.

Ophelia is a wild child, neglected by her father Polonius (Dominic Mafham), who is introduced driving a cart bearing his two young children into Elsinore, and who works his way up to the position of trusted advisor to King Hamlet (Nathaniel Parker). Without a mother (the film works with clearly defined gender roles, though attributes these to the conventions of this particular court), Ophelia is filthy and poorly dressed, preferring to run about in nature or explore the cellars of the palace. When she interrupts a toast being offered by Claudius (Clive Owen) to the young Prince Hamlet, Gertrude (Naomi Watts) takes pity on the bold young woman and offers to take her on as one of her ladies-in-waiting. A quick montage of hair-brushing and aggressive washing later, and Ridley emerges as an Ophelia who looks the part of a noblewoman, but who can’t dance, wears flowers instead of jewels, and is derided by her Mean Girls companions for her lack of money and graces.

As a character study, the film takes a simple but clear line. Ophelia’s affinity with nature is coded as unladylike and improper in the eyes of the court, but is presented by the film as one of the ways in which her superior depth and insight manifest, along with her unique ability to read and her knowledge of the classics. Gertrude favours her for her ability to share more than platitudes with her, tasking her with reading to her (hilariously, soft porn rather than prayer books) and, subsequently, with more discreet tasks. By setting her up as the quiet one who remains out of the court gossip, but who is secretly accomplished, the film develops YA tropes of the protagonist with hidden depths whose ability to watch and listen become all-important. As a reworking of Hamlet, this enables the film to place her at all of the key points within the play’s action as either watcher or participant, but also to suggest that the play’s passive Ophelia is doing much that we cannot see.

The first half hour is set-up before King Hamlet is killed (a piece of news revealed, interestingly, by Rosencrantz and Guildenstern skipping down a corridor shouting hurrahs for the new King – these two are barely seen, but here are firmly in Claudius’s pocket throughout), establishing Ophelia’s prior relationship with George Mackay’s Hamlet, who falls in love with her after seeing her swimming, setting up a really strained set of fish images to which, in fairness, the screenplay commits wholeheartedly. It is established that Hamlet and Ophelia can never be together owing to their different statuses, but Ophelia is nonetheless furious when she finds out Hamlet is leaving for Wittenberg the night after their first kiss. The other part of the set-up introduces a healer/witch in the forest, Mechtild (also played by Watts) who supplies the Queen with a potion that keeps her youthful.

Following the death of Hamlet and the very sudden coronation of Claudius and his marriage to Gertrude, Shakespeare’s narrative takes over even if the language does not. The screenplay is a clever adaptation, retaining enough of the form and structure to be recognisable, dispensing with what wouldn’t work (none of Hamlet’s soliloquies feature), and making reference to quotations and thematic points when the original references won’t neatly fit; in an early playful duel between Hamlet and Claudius before Old Hamlet’s death, Claudius accuses Hamlet of failing to act when he should be more decisive. Key establishing scenes such as Ophelia’s initial farewell to Laertes (Tom Felton) are played more closely to Shakespeare, using modern English with a standard historical-drama sheen and capturing the essence of the source.

This film’s Claudius is an out-and-out baddie who, we learn, impregnated Mechtild (who is, quite obviously, Gertrude’s sister) and then had her declared a witch, driving her out of civic life, though not before she faked her own death with a potion. The Mechtild-Claudius-Gertrude love triangle is by far the silliest part of the whole film and could have quite happily been cut; a phantom figure who Ophelia sees on the battlements early in the film turns out to be Claudius, who is running errands for Gertrude to Mechtild’s lair in order to get her potions. Claudius is a smarmy, dangerous, brutal ruler, and Owen has great fun with him. Gertrude, on the other hand, is more complex, showing genuine care for Ophelia and apparent real grief for her husband, while also lounging happily in bed with Claudius and showing herself able to act decisively on her own behalf.

Ophelia’s role in the film is largely as the unacknowledged ally of Hamlet, who barrels back into the castle and initially refuses to kneel for the new King, only finally bending the knee at the point of treason. Hamlet’s grief and his love for Ophelia are enmeshed with one another, and Ophelia thus becomes the voice of reason and clear-sighted action, trying to direct him and protect him. The two marry secretly, Hamlet disguising himself as a country boy so that they won’t be discovered, a decision that brings down Gertrude’s wrath upon Ophelia when she feels Ophelia has debased herself. The pivotal scene is the nunnery scene, in which Ophelia is brutally manhandled by Claudius into the position of bait. As Hamlet tries to greet his new wife in front of the eavesdropping king, Ophelia feigns the return of remembrances while whispering to Hamlet that he was right about the poison. Hamlet’s ‘go to a nunnery’ is a plea for her to go to a safe haven that he knows, the details whispered and the insult shouted as Hamlet storms off.

This scene encapsulates the film’s strategy for exploring how women can find agency in a man’s world. Ophelia has little ability to speak overtly, her position in constant jeopardy, and thus she uses her time in the shadows to her advantage. She whispers in Hamlet’s ear, stays silent in the Queen’s bedchamber in order to learn what is going on, and quizzes Horatio (Devon Terrell) and others to get filled in on the plot. Hamlet gets on with his own plans in the background, and we hear tell of his madness and actions such as killing Polonius, and the film assumes that we know enough of that story. Instead, seeing things through Ophelia’s eyes, the film structures Hamlet around the moments where she is able to intervene. A second crucial scene is ‘The Mousetrap’, realised in what is actually quite a well-done shadow play featuring several actors (wearing modern vests and blacks, bizarrely) posing as a tree and creating a silhouette of a serpent dripping poison into a shadow’s ear. Hamlet’s insulting of Ophelia allows him to bring her close so that he can ask her why she hasn’t fled to the nunnery, and their proximity also allows her to intervene when he immediately draws his sword on the disturbed Claudius, saving him from a potentially catastrophic public assault.

The film is structurally unbalanced, in that the second half of Hamlet is rushed through in ways that risk making emotional nonsense of Ophelia’s own arc. Polonius’s death and any grief Ophelia feels, for instance, pass in the blink of an eye, and there’s never a clear sense of whether Ophelia actually cares that her father is dead. Horatio saves her from throwing herself off the battlements when she believes Hamlet is dead, but this sequences plays as quite juvenile, as a jealous maid spitefully tells Ophelia that Hamlet has been thrown off the ship bound for England; Horatio’s revelation that the ship hasn’t yet left harbour just makes Ophelia’s grief seem uncharacteristically premature for this usually savvy character. And the very sudden introduction of a plotline in which Claudius insists Ophelia marry a nasty piece of work called Edmund may hint at a Shakespearean Cinematic Universe, but acts to push Ophelia into a bit of a narrative dead end, giving Ridley crisis after crisis to escape from rather than allowing space to deal with the emotional fallout of Polonius’s death.

All of this builds to Ophelia’s key act of defiance – her faked madness as she spins into the court, dropping flowers into the laps of Gertrude and Claudius along with loaded comments and provocations, before she runs off into the woods, takes the potion that will make her seem dead, and floats off into the lake. Ophelia’s faked death allows her to return and reunite with Hamlet just before his climactic duel, but at this point Ophelia has become nothing more than a spectral spectator of the story. She and we watch as Hamlet and Laertes duel and poison one another; then, in a fanfic-style twist, Gertrude screams, takes a sword and plunges it so deep into Claudius that it goes right through him and the throne in a moment of superhuman strength – before, bizarrely, Mechtild then marches into the court with an army who begin slaughtering Denmark’s nobility, beating Horatio, and generally taking over. Gertrude poisons herself rather than wait to see her sister take over. The cathartic pleasure of seeing Gertrude kill Claudius is somewhat overwhelmed by the resolution of the sillier plot, and while the idea behind the Mechtild story is a valuable one, exploring a different kind of sidelining of women and its consequences, it’s one plot too many for the film to sustain.

For all that the film tries to claim agency for Ophelia, her only eventual agency is her ability to save herself. The reworkings of key scenes from Hamlet that show Ophelia’s guiding hand in saving Hamlet, exposing the plot and offering ways to safety come to naught, ripples in a river that course corrects in the eventual deaths of all the main characters on cue. Ophelia’s faked death, however, means that she gets to go to the nunnery, have Hamlet’s child, and appear scenically in nature in a closing montage, returning to an idealised form of existence, completed by becoming a mother but without a bratty husband or the baggage of politics. In some ways it’s a failure of imagination on the film’s part, seeing Ophelia solely in relation to gendered roles, but in other ways it at least offers a version of Ophelia who goes beyond Pretty Dead Girl, taking the play’s scenes of abuse, misogyny, victimisation and death and seeing them as choices made by Ophelia in the service of preserving her own identity. The story of Elsinore’s court becomes a byline in her own origin story, which she now gets to write for herself.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply