September 4, 2020, by Peter Kirwan

The Winter’s Tale (Renegade Theatre) @ Shakespeare’s Globe (via Globe Player)

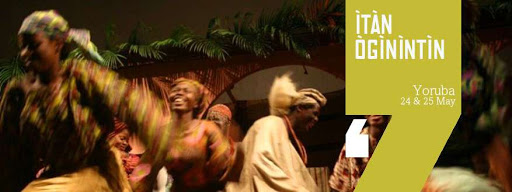

The Winter’s Tale is structured, at roughly its mid-point, around a passage of time. It’s a play whose passage of sixteen years allows for an evocation of long regret and mourning, of aging and changing, of memory and forgiveness (or not). But in Ìtàn Ògìnìntìn, performed at the Globe as part of the 2012 Globe to Globe Festival, this passage of time is dramatically reworked, with the chronology of the play radically reversed to concentrate instead on the cyclical and mythic. Julie Sanders’s invaluable review of the production from 2012 introduces some of the cosmological underpinnings of a production that names its characters after gods (Leontes becomes Şàngó, god of lightning and justice; Hermione is Ǫya, who becomes the goddess of the whirlwind) and allows its magic and mystery to take on a mythic significance.

The production begins with dislocation, as Antigonus (Adékúnlé Smart Adéjùmǫ – I use the English versions of the character names as I don’t have a complete list of the Yoruba equivalents), holding a bundle to signify baby Perdita, is surrounded by men holding oars, rowing. Time (Motúnráyǫ Oròbíyi), a constant presence on the stage who acts as intermediary, singing to the audience and for the company, sets this tableau to music. A frustration of this mediation of a Nigerian production for a UK audience is that the subtitles are extremely selective, only offering Shakespearean text at the equivalent moments and leaving the new text untranslated, which particularly affects Time’s role. Nonetheless, her song offers an elegiac accompaniment to Antigonus’s dislocated, anxious presence as he arrives in Bohemia and is killed – not by a bear, or at least by someone made up to look like a bear, but by a man, who jumps on him, wrestles him to the ground and throttles him to death before dragging him offstage. The production thus locates us, not in brewing climate of jealous in Sicilia, but in the unpredictable and disorienting space of transition and change in which Perdita’s real life begins.

The production’s extraordinary choice to begin with the final scene of Act 3 and segue straight into Act 4, before suddenly entering a flashback at the point when Florizel and Perdita prepare to flee Bohemia and only then showing the Sicilian story of the first three acts, has a profound effect on the play’s structure and narrative. Our framing characters are the child Perdita, the Clown and the Old Shepherd – the latter two of whom get to open the play with a hilarious comic routine as they find Perdita, and as the Clown (Adisa Moruf Adeyemi) illustrates the shipwreck with an oar that he keeps smacking his father with – and the overwhelming weight of the first third of the production is comedy. From the brilliant pickpocketing scene performed by Adeyemi and Aniké Alli-Hakeem (Autolycus) – with Autolycus forcing the Clown to carry her whole weight, while waving the stolen purse gleefully around for the benefit of the audience behind the Clown’s back – to the amusing performance of a surprisingly comic Camillo (Ǫlásúnkànmi Adébàyǫ), the comic tone frames the experience of the adult Perdita (Olúwatóyĩn Alli-Hakeem) as one of joy as she enters maturity, both as the richly dressed hostess of the equivalent of the sheep-shearing, and as the lover of Florizel (Joshua Adémólá Àlàb), who both defers respectfully to her and picksher up in a truly romantic dance. Their courtship is accompanied by a spectacular festival, including two dancers in enormous multi-storey column costumes, audience members dragged on stage, and a fierce on-stage percussion ensemble, that create a vibrant energy around Florizel and Perdita’s dancing and wooing. The early investment in the two lovers invites us to see this as their story, and to only retrospectively learn what had brought them both to this place.

The trade-off is in the relative side-lining of the Sicilia story. While the playing of acts 1 to 3 is superb, and gave plenty of space for Leontes and Hermione to develop their relationship, the abrupt shift back to the relatively disposable end of 4.4 (Clown, Shepherd and Autolycus) after the interval, followed by the return to a smiling Leontes welcoming the renegade Perdita and Florizel, is less successful, not allowing enough sense of a passage of time and the space of mourning/loss (though a long sung passage by Time may offer more here for those fluent in the production’s spoken language). This is, perhaps, less important in a version of the play that imagines the great kings and queens as manifestations of gods rather than fully realised human characters, but it in particular seems to leave Hermione stranded in the centre of the play and quite quickly revived, rather than her loss being the motoring action for what happens. The loss here is, I think, worth the experiment, and only really affects the flow of the production at the start of the (short) second half; I don’t know if the production was always played with an interval in other venues, but I suspect that a more managed shift back to the ‘present’ story line, rather than the interruption of the performance with an interval, would have helped with the transition here.

Another fascinating change in emphasis is the foregrounding of Polixenes (Olarotimi Fakunle), an angry and powerful presence whose version of toxic patriarchy sets the violent tone of the play, rather than (as usual) Leontes being the one to drive the play’s darker edges. In a sequence reminiscent of As You Like It, Camillo and Polixenes are first introduced returning from a hunting expedition with a dead stag and wielding rifles. Polixenes’ rifle is rarely out of his hand, except when in disguise at the Shepherds’ festival, and this weapon acts as an extension of his arm, regularly pointed at those who cross him. Paired with the comic Camillo, Polixenes is an intimidating and quickly angered presence. His intrusion into the sheep-shearing festival is aggressive, as typical, throwing Florizel to the ground. But when the production travels back in time, we see these domineering impulses in him long in his past. When Camillo informs Polixenes of Leontes’ betrayal, Polixenes holds Camillo at gunpoint and threatens him, his first impulse being to violence rather than to fear, and his inherent violence makes his prospective confrontation with Leontes particularly tense.

Leontes (Olawale Adebayo) is not someone you would want to cross. He is physically imposing, a towering presence on the stage, and deliberately takes up space. When threatening Camillo into killing Polixenes, he forces Camillo to the floor and stands with legs planted far apart, holding totemic symbols in each hand that extend his reach, and spreading himself to dominate the stage. He uses his prostheses to pin Camillo down – his sceptre looks like a battle axe, and he holds it aggressively – and he moves quickly and powerfully about the stage. Part of what drives his shift in mood is the similar dominance of Polixenes, as if the stage literally isn’t big enough for the two of them. The introduction to Sicilia sees Leontes and Hermione (Kehinde Bankole – the only Hermione I’ve ever seen not wearing a prosthetic pregnant stomach) dancing together publicly, taking delight in one another’s bodies as they move around the stage, before Polixenes then takes his turn with Hermione. As Leontes watches, Polixenes picks Hermione bodily up and carries her around, and it’s at this action that Leontes’ expression changes, glowering as Polixenes performs the same act with Hermione that we have already seen Florizel perform with Perdita. Polixenes continues to be physically intimate with Hermione – showing her how to shoot, putting his arm around her as they leave. There’s no intimation of infidelity here, but Leontes appears to be objecting to Polixenes’ free-ness with his space and his wife.

As such, Hermione feels like collateral damage in a feud that is much more about a pissing match between the two men, and she is having none of it. Hermione and Paulina (Idiat Abisola Sobande) are independent and fearless, and never seem to be cowed by Leontes’ violence. In many ways, this seems to frustrate Leontes more. Paulina walks directly up to Leontes and places the baby Perdita at his feet; his outrage at her presumption leads to him shortly after raising his foot as if to stamp on the baby, only for Antigonus to throw himself bodily in the way of Leontes’ foot. Paulina is unmoved, though, and her confidence in what Leontes will do is a destabilisation of his power; the very dignity of her performance seems to slow the production down to her time. Leontes is further humiliated by the mystic figure who stands in for the Oracle, coming in person to deliver the news that Leontes is at fault (though not without some fear, as he backs off into the pit to deliver his verdict as Leontes advances furiously on him). And in the trial scene, Hermione really comes into her own. She is shackled with heavy chains around her wrists, but in a metal-grey costume and given centre-stage, she moves with a furious confidence, seeming to put Leontes on trial rather than submitting herself. Earlier, she had walked away with disdain from his accusations; here, she faces him uncompromisingly and undefeated.

The power of Hermione makes it all the more disappointing that the quick shift to interval after the report of her death doesn’t give much time to register its catastrophic impact. Mamillius, too, feels relatively unconnected here – he has a great song that he performs for his mother in place of the whispered story (reminiscent to me, in retrospect, of Philip Hamilton’s rap in Hamilton) – and the double deaths are swept away quickly in the interval and in the return to the comic business of Autolycus. Further, when we return to Leontes a few minutes later in Act 5, he seems okay. He is smiling and welcoming of Florizel and Perdita, and joyful in the return of Polixenes. This is an excellent bit of business, as Polixenes runs on stage with his ever-present rifle, while Leontes meets and confronts him holding his two weapons. The two run towards one another in what seems to be their final battle – and instead they jump and chest-bump before embracing. The quick forgiveness between the pair is smile-inducing, but again leaves little sense of the hole – if any – that Hermione’s loss has left. There’s still some tension – while there is laughter from the audience when Florizel prostrates himself before his father, Polixenes isn’t smiling, and still isn’t ready to cede any of his patriarchal domination.

Perhaps this is the point, though. In an extraordinary final scene, Hermione’s sense of having been forgotten is played for far more significance than I’ve seen in any other Winter’s Tale. The statue is carried on wrapped in a shard, in a reversal of the motion in which her unconscious body was earlier removed from sight. Hermione stands centre-stage on a plinth, and Paulina leads a long ritual to awaken her, praying quickly accompanied by frenetic percussion before offering a loud shout, three times. The long pauses after each cause some laughter from the audience, as if something has gone wrong, but I found this unbearable, giving a sense of the difficulty of awakening the statue – there is no implication here that this is a trick. Eventually, Hermione suddenly gasps and stumbles off the plinth. She looks pissed.

I’m in no way qualified to speak to how this retelling fits with the mythology of Şàngó, Ǫya, and Ògún, the god of war (who is embodied by Polixenes). But in Bankole’s performance, Hermione becomes truly god-like, resurrected in a form that seems to sit somewhere between mortal and divine. Her head is lifted – she seems disoriented as those around her celebrate, and when she speaks, it is to lift her head high and to call upon the gods, only belatedly noticing and acknowledging Perdita, who is knelt at her feet. But the real twist comes as Leontes roars and celebrates, striding about the stage and celebrating loudly, without even really looking at her. Hermione turns and returns to the plinth, resuming her frozen position as Paulina covers her up again. This is initially hilarious – it looks as if she is making a comic point about him ignoring her – but it quickly becomes something much more serious. Leontes is devastated once more, crumpling before the statue as it is covered. This is Hermione’s choice, clearly. There is no redemption here for Leontes, no forgiveness – just a temporary return to motion in order to acknowledge and bless the return of her daughter, before returning once more to death (or something like it, at least). But I also found this crushing; not for Leontes’ sake (why does he particularly deserve happiness?) but because the cruel lie of The Winter’s Tale has always been that we can have those who we have lost restored to us. The Eurydice-like return of Hermione to a different plane, after the tease of her resurrection, insists more strongly than most on the consequences of Leontes’ earlier actions, on death being a point of no (permanent) return. And as the company leave the stage, Leontes broken and the covered statue remaining centre-stage, there’s a profound sense of finality.

If there is any hope, it is to be found in the curtain calls, as the company slowly return. It’s significant, I think, that Autolycus is the first to come back. Autolycus is a highlight of the production, a protean, ever-changing enigma who is irreverent, funny, and undermines all around her. She takes pleasure in her costume changes (her delighted face when she puts on Florizel’s clothes is a particular treat), and even when she is drummed offstage by the Clown in her final appearance within the play proper, she still seems to be as feisty and irrepressible as ever. And she leads the rest of the company back out for their bows and celebrations. There’s a lovely contrast as the large Leontes and Polixenes pick up the tiny Autolycus and make her bow in mid-air for the crowd, before the two of them turn to the statue, finally unveil it, and bring Hermione gently forward for her much more dignified call. It’s in the magic of theatre that a true return can be enacted, not within the fiction. And it’s the magic of theatre that refuses to go away, as the percussionists have to be bodily dragged off the stage before they stop playing their repeated encores.

Thanks as ever to my #WTWatchParty co-conspirator Nora Williams, and to those who joined in our live tweet-along.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply