June 8, 2020, by Peter Kirwan

The Merry Wives of Windsor @ Shakespeare’s Globe (webstream)

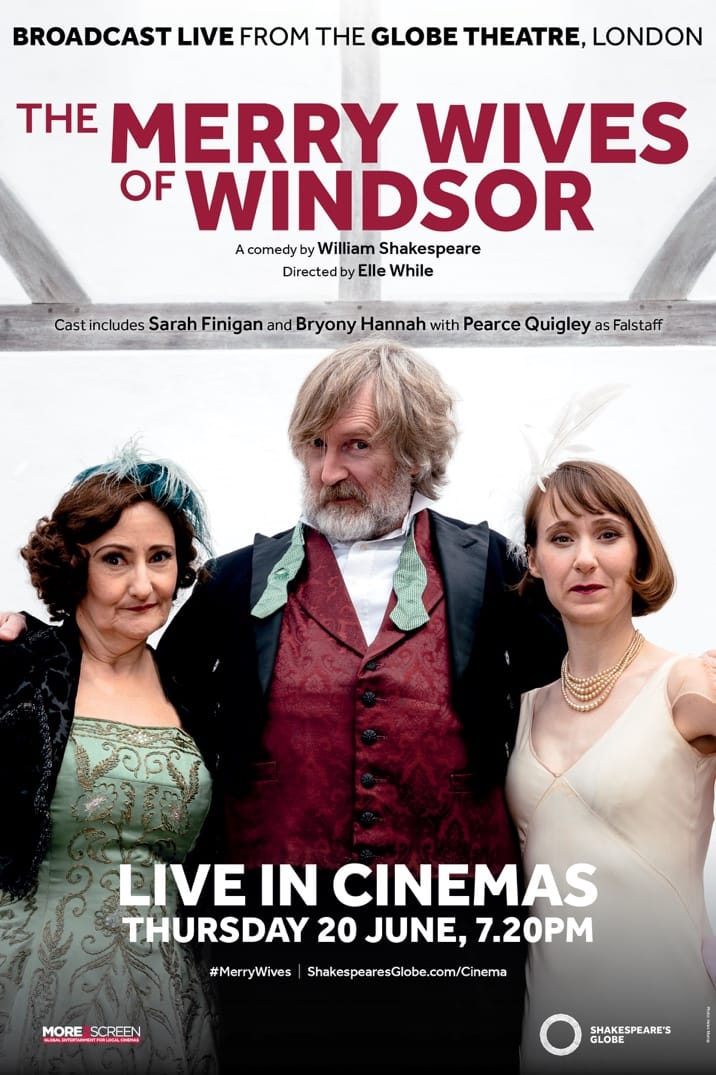

In releasing its 2019 The Merry Wives of Windsor as one of its free YouTube premieres, the Globe justly celebrates one of its finest ensembles (who later in the year went on to perform in Bartholomew Fair). Elle While’s thirties-set production is a jolly, entertaining farce that treats the play with the light touch it deserves (albeit with the anti-immigrant jokes, as always, failing to provoke the critique they deserve), and Frank Moon’s pitch-perfect period score and songs lend a cabaret feel to the performance. While the screen recording sadly doesn’t capture the energy and repartee that the stage production clearly evoked, it’s still a great document of a fun production.

The highlight – of everything he does, but especially here – is Pearce Quigley, taking a rare leading role as Falstaff. Quigley is the greatest actor bar none ever to work the Globe stage. His arch, slightly camp manner has a detachment that allows him to slip in and out of locus and platea, to deliver his whole role as if it’s one enormous aside. The Falstaff of Merry Wives is a perfect role for him because it distances the actor enough from the character to enable both him and the audience to delight in the knight’s humiliations. He invites the audience to cheer him on – literally at times, as when he first hears that Mistress Ford (Bryony Hannah) and Mistress Page (Sarah Finigan) have accepted his letters, screaming ‘YES!’ as he runs around the stage and calls for cheers, before popping a party popper or sounding a sad little party blower. But the cheering on is in service of enjoying his downfall. It’s a performance that manages almost single-handedly to remove the cruelty from the play, granting permission to enjoy it.

Quigley’s Falstaff is avuncular, self-absorbed, and even a little queer; the production doesn’t make too much of it, but moments such as Falstaff placing Robin’s (Joshua Lacey) hand on his arse as the two walk off with their arms around one another, or leading the disguised Ford (Jude Owusu) off stage gently by the hand, are not titillating so much as they’re indicative of Falstaff’s indiscriminate sexual interest, which also extends to Mistress Quickly (Anita Reynolds) and the Hostess (Anne Odeke). But at the same time, Falstaff isn’t driven by uncontrollable desire, but by a kind of detached interest in what he can win. He’s a hustler, but a modest one, down but not out when his plans don’t come to fruition, and just as happy to slip back into taunting the audience by repeatedly pouring water on the same small group at the front of the pit.

The little jokes are what keep the production going. A completely pointless bit with a fake windowpane that Falstaff crosses behind while talking, momentarily muting himself as he does so, is in there for no other reason than someone thinking it was funny, and it’s a great sight/sound gag. When he turns up blindfolded for his second tryst with Mistress Ford, Falstaff wanders into the pit and grabs a gentleman for a long embrace before realising his mistake. The whole company live for the little adlibs, especially in Quigley’s consummate delivery of repetitions, seeming to disappear outside the role and to observe the words falling alongside one another, before suddenly pulling them back into himself and barking an order. And when he sits on the downstage edge after his final humiliation, he’s still presenting himself as chatting happily to the audience. It’s really quite joyful.

Quigley’s turn is excellent, but this is an ensemble production, as is especially obvious in the slapstick, choreographed by Phillip d’Orleans. This takes all forms. Boadicea Ricketts as John Rugby gets a great early sequence, being tugged out of the cabinet where Mistress Quickly has hidden her by a furious Dr Caius and sprawling over the floor. Odeke and Zach Wyatt have the fun of playing the buckbasket carriers, and have an elaborate skit in which they fail to lift the basket carrying the weighty Falstaff, and settle instead for rolling it into the pit and out (one presumes that Quigley got out in good time, but it’s a very effectively staged bit). And the Witch of Brentford occasions a whole Keystone Cops-style chase about the stage, featuring Falstaff screaming at the sight of the buckbasket, off-stage smashing, a gun being produced and Ford finally attacking with a frying pan.

Alongside this are some entertaining bits of period-specific business that do important work in tying together the community of a play with a large cast of characters. The best of these is an extended charades-style mime in which the merry wives illustrate for their husbands and Hugh Evans (Hedydd Dylan, an actual Welsh actor playing the parson) what has really been going on; this offstage explanation in the play here works nicely as a comic recapitulation that allows the women to take agency in owning their tricks, which especially leaves Ford floundering. The two wives have a great time throughout, with Mistress Ford in particular using a riding crop to set up a series of fetishistic encounters with Falstaff that place him in a sub relationship even before he is bundled away into hiding; the gestures towards treating Mistress Ford in particular as an early feminist are again very light, but are there to be read as she enjoys wielding her power over Falstaff. The musical interludes, including Forbes Masson’s Page leading a full ensemble song early on, and a big swing number at Herne’s Oak, are also lovely bits of staging that show off the cast’s talents.

The subplots work less well. Richard Katz as Dr Caius plays up the French pronunciation jokes for all they’re worth, Ricketts and Wyatt play Hollywood-era lovers as Fenton and Anne Page, and Lacey works hard as Slender, but the scenes are too busy to coalesce into something more coherent (a challenge for many productions of Merry Wives). As with the same ensemble’s Bartholomew Fair, though, the pleasure is in watching this excellent ensemble hang out together. The busy-ness of the stage, the party atmosphere (especially with Masson’s Page hosting, always with a drink in hand), and the quickly developed plots and collaborations, all contribute to the convivial atmosphere that is clear at all times in the recording. The celebration by the crowd of every costume change Falstaff makes, of every time two lovers get together or reconcile, of every success and every failure, shows a Globe ensemble working at the top of its game.

thank you