March 6, 2020, by Peter Kirwan

The Revenger’s Tragedy (Cheek by Jowl/Piccolo) @ The Barbican Theatre

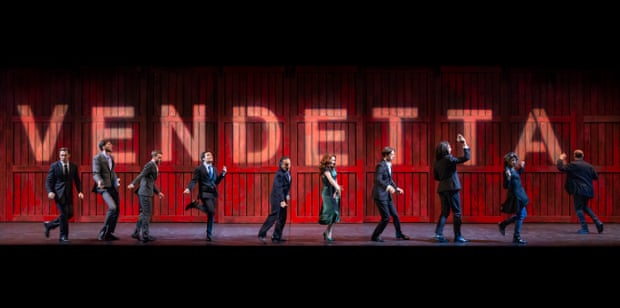

In producing a play that turns repeatedly on deceitful appearances, both in the spectacles of power and in staged tricks played on the unsuspecting, Cheek by Jowl’s Revenger’s Tragedy turned theatre itself into the grand metaphor. At the production’s opening, with a stage manager in a headset watching, Fausto Cabra’s Vindice clicked his fingers to bring on the company as a line of dancers, all manically gyrating and twisting as if their lives depended on it. Perhaps they did. The characters were introduced one by one, taking communion from a bishop while Vindice remarked on their crimes, before Vindice pulled out the skull of his murdered fiancée and pushed it into the disgusted faces of his opponents, before allowing them to dance off the stage. Vindice was the stage manager of this world, and everyone danced to his tune.

This introductory sequence welcomed the audience to a slickly choreographed world in which corruption pervaded all levels of society, and these levels all folded into one another. This was the latest in Cheek by Jowl’s sequence of ‘box’ productions (following Measure for Measure, The Winter’s Tale and The Knight of the Burning Pestle) in which the worlds of the play emerge from one of Nick Ormerod’s enormous onstage boxes. Here, the wooden edifice spanned the width of the Barbican stage. Festooned with the word ‘vendetta’ as the play opened, the box had several doors to allow access on and off the forestage, and sliding components which opened to reveal miniature sets that slid out, often at Vindice’s command. The contained environments of the production gave a window into this world’s theatres of power, where everyone was attempting to gain, consolidate or abuse what little sway they had.

The self-referential Revenger’s Tragedy was thus a perfect match for Declan Donnellan and Ormerod’s interest in exploiting the theatricality of power, and the production drew both comedy and serious purpose from the ways in which characters performed themselves in private and public spaces. A key early scene was the trial of Junior (Flavio Capuzzo Dolcetta), who strode confidently across the stage to face Marco Brinzi’s Judge, sat centrally on a dais. Junior’s mockery of the whole situation beautifully spoke to the protected privilege of the elite, and Dolcetta brilliantly kept up Junior’s absolute confidence in his immunity until right before his death. In the trial scene, he made to sit in a chair before the Judge, but was made to stand. However, the Judge was thrown off by the arrival of Massimilliano Speziani’s Duke, who entered with a ‘Don’t mind me’ air and proceeded to sit directly behind the Judge, leaving the hapless lawmaker stumbling over his lines as he looked nervously over his shoulders. Then, the Judge’s dais was repeatedly invaded by the Duchess (Pia Lanciotti) and Junior’s brothers Supervacuo (Christian Di Filippo) and Ambitioso (David Meden), all of whom showed brazen contempt for the court. Following the Duchess’s pleas on her knees (making sure her dress was hitched well up), the Duke finally postponed the verdict, ending a charade of justice that few believed would be carried out.

In important ways, then, Vindice’s playacting and metatheatrical control was set from the start against an apparatus of state power with complete confidence in its own invincibility, and this conflict drove the production’s fast-paced action. Cabra’s Vindice was a disaffected ghoul in black, who donned a blonde wig as Piato and was gleefully reckless in his pursuit of his schemes. He was accompanied throughout by his brother Ippolito (Raffaele Esposito), a nervous wreck of a man who brought up the tail of Vindice’s original line of dancers and who spent much of his time on stage silently remonstrating with Vindice behind the back of whichever mark Vindice was targeting, gesturing wildly in a bid to get Vindice to moderate his actions.

As Vindice went to work, the production took its time to work through the varying spheres of corruption, giving a surprisingly full account of the play that went further than most I’ve seen in exploring the subplots. Vindice’s initial meeting with the languid Lussurioso (Ivan Alovisio) saw him sitting immediately behind the young prince as if a therapist or confessor; as Lussurioso announced that he wanted Vindice to woo his own sister on his behalf, Vindice froze. The scenes with Gratiana (Lanciotti again) and Castiza (Marta Malvestiti) saw Vindice don a priest’s garb (with a half-hearted ‘Hail Mary’) and worm his way into a garden party. Castiza gave Vindice short shrift, at first surprised to find a necklace suddenly placed about her neck, but then slapping the false priest hard across the face, much to Vindice’s delight. Gratiana, however, was a different story. As Vindice turned on the charm, she initially thought that she was being propositioned by Lussurioso, a delusion Vindice allowed her to continue in for a few lines. But as he began teasing Gratiana with promises of wealth, the older woman began getting turned on, spontaneously kissing her son passionately (a second freeze on his part). Then, as Castiza was brought back in, Gratiana and Vindice indulged themselves in lavishly buttered sandwiches which Gratiana kept shovelling into Vindice’s mouth, the two of them consuming more and more as Gratiana was carried away by the possibility of future riches, her conspicuous consumption with the sandwiches mirroring the ambition overtaking her as her squeaks reached an ever-higher pitch. Castiza, for her part, remained ignored on the sideilnes.

The sexual indiscretions of the Duke’s inner circle lent themselves to comedy. Spurio (Errico Liguori) clearly thought he was the lead character in this play, presuming to address the audience repeatedly; his long curls marked him out from his legitimate brothers along with his habit of wry commentary. The same privilege was enjoyed by the Duchess who, at the end of the court scene, kept sobbing until sure that everyone had left, before letting herself relax and revealing that she was fed up of the Duke. She wasted no time taking Spurio’s top off as she seduced him, and the two were later seen with whip and lead, the Duchess fetishising the sculpted body of the younger man. For his part, the Duke was a somewhat hapless figure, tiny enough that when standing on his own bed, he was still not quite as tall as the lanky Ambitioso. When Lussurioso was tricked into breaking into the Duke’s bedroom, the Duke and Duchess were caught in flagrante, the Duke pumping away under the sheets while the bored Duchess rubbed cream into her hands and remembered to offer a gasp every now and again while waiting for him to finish. The Duke initially used the Duchess as a shield before realising who had broken into the room, at which point he attempted to reassert his authority.

The comedy double act of little-but-clever Supervacuo and big-but-brainless Ambitioso came to the fore at this point, first in their clumsy attempts to manipulate the Duke into ordering Lussurio’s death (a plot the Duke saw right through, standing upright on the bed to tell the audience even as he placed a hand on his sons’ heads), and subsequently in their hapless attempts to rescue Junior. Donnellan intercut the scenes of Lussurio’s release (in which he spoke directly to a television camera, celebrating his freedom) and Ambitioso and Supervacuo bringing the execution order to the prison (also spoken to a TV camera as they prepared the media image of their reluctant complicity). Their reckless acts led to a surprisingly moving final scene for Junior, who continued to smugly exercise even as the prison doctors and priests confessed him, checked his heart, and stripped him for execution; his reaction as he eventually realised what was happening to him, and his screams as he was carried off upstage, were surprisingly heartfelt, the production giving weight to his fear. Pleasingly, though, the delivery of his head to his brothers was played for laughs. Lussurioso entered and began speaking to his brothers from a distance, leading them to tap on the coolbox containing Junior’s head in fear as they tried to work out how Lussurioso was speaking to them. Ambitioso screamed himself hoarse on finally looking in to find Junior’s head, prompting Supervacuo to give him his vaper to use as an inhaler to calm himself.

The balance of comedy and horror was most finely realised in Vindice’s revenge on the Duke, a tour de force that complicated the play’s antiheroes. The sequence began as comedy again in an elaborate game of blind-man’s-buff, with Ippolito desperately trying to get Vindice’s attention while Vindice led the blindfolded Duke around the stage towards the skeleton that Vindice had waltzed onto a couch at the scene’s start. Vindice had Ippolito tear off his shirt and offer his bare arm to the Duke, pulling the Duke into the illusion; Ippolito even, to his own disgust, licked the Duke briefly. But when the Duke finally kissed the skull and staggered back, the transformation in Ippolito was staggering. Suddenly overcome by the success of their trick, Ippolito whooped and jeered, screaming in triumph. Topless, it was he who carried out the bloody mutilations of the Duke, and the rest of the company entered (including one with a live video camera) to bear witness as Ippolito tore out the Duke’s tongue and cut off his eyelids, the camera capturing snippets in excruciating detail while also focusing on the deadpan expressions of spectators. While Vindice was the one who finally cut the Duke’s throat, it was the bloodlust that came over Ippolito that resonated the most, the once anxious brother becoming full-blooded co-conspirator.

Repeatedly, then, the production staged people learning to love the power they wielded when given it. Junior revelled in his immunity in the court (until that power was stripped from him in prison); Gratiana consumed her sandwiches with reckless abandon (until Ippolito and Vindice returned to her and threatened her, leaving her shaking and ashen); and Ippolito himself was overcome by the need for vengeance. Lussurioso, too, was quick to double down on his own repressed desires. He joined Vindice and Ippolito for the assassination of the drunken Piato (the Duke doing excellent dead acting in a Piato wig), but was an outright coward, pleading with the two brothers to go forward and do the work first. Even after they had stabbed the corpse (and mimed its arms flailing around), Lussurioso still needed proof that ‘Piato’ was dead, before finally tentatively sticking a knife slowly in himself, then again, faster and faster until Vindice and Ippolito were howling and clapping in time with the thrusts. Lussurio’s glee turned to terror as the Duke’s body comically flopped to the floor and Vindice – playacting a dog – tore his wig off with his teeth.

Notwithstanding his shock, Lussurioso quickly embraced his new position, as the court gathered around the body of the Duke and acknowledged him as the new Duke. Here it was the Duchess’s turn to fall, as Lussurioso drew everyone into a collective family circle, promising fealty and love among them all, until pronouncing the Duchess a whore and banishing her. The Duchess’s look of fawning hope turned to hopelessness, and she walked across the stage holding Ambitioso and Supervacuo’s hands. However, those two both peeled themselves away, embraced her farewell, and returned to the other side of the stage, leaving her to stumble off by herself, metatheatrically thumping on the scenery to be let out.

The finale saw the most radical rewritings of the production. The set-up for the masque was beautiful, with Spurio, Ambitioso and Supervacuo embracing in a display of brotherly love while all promising to murder one another. The newly crowned Lussurioso then emerged on a dais with a throne, revelling in his power as he watched a shooting star (projected on the back screen) and cackled and sang madly, his courtiers withdrawing nervously from him. But his theatrical apparatus of power was immediately challenged by Vindice, who clapped his hands to bring back the opening line of dancers, the company filling the stage with frenetic, automatic movement. Throwing the text of the masque out, the company instead devolved into a series of murders: Ippolito and Vindice stabbed Lussurioso; Supervacuo killed Ambitioso (brutally, a knife through the skull); Spurio killed Ambitioso; and then the entire company turned on Vindice, stabbing him collectively, before an enraged Ippolito murdered Spurio. And at that point, the whole thing dissolved into an orgy of violence, the cast all wrestling with one another on the floor as the music and dance continued.

And then, looking on, the stage manager flicked a switch and bright stage lights went up. The cast relaxed, sighing at the relief of finally being able to stop, and started dusting themselves off, milling around the stage, joking together, and wandering offstage, refusing the closure of an ending. Brilliantly, Middleton’s cycle of violence here became deliberately unpatterned, an entertainment that had gotten out of hand, and which could only be stopped by an act of metatheatrical intervention. The scenarios devised by Vindice were no more ‘real’ than the artificial trappings of power behind which the privileged hid, and the emptiness of revenge left nothing to be resolved or tidied up – just actors, playing a part, relieved to call it a day and leave it all behind.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply