January 25, 2020, by Peter Kirwan

Teenage Dick @ The Donmar Warehouse

The best high-school Shakespeare adaptations don’t simply look for one-on-one equivalences in their new milieu for the Shakespearean text, but engage deeply with the concerns, clichés, and stakes of their environment. To translate wars and intrigues to basketball courts or class president elections does not require matters to be trivialised simply because they are no longer happening on a world stage; a good adaptation empathises with the perspective of its characters, understands that high school can not only feel like life and death when it makes up your own world, but can also be about life and death, and requires as serious a treatment as any other subject.

This is something Mike Lew’s Teenage Dick understands. The play premiered in 2018 at the Public, and is a witty, insightful riff on Richard III that takes cues from Shakespeare to explore issues around disability, bullying, betrayal, and shaming culture that skew in a very different direction. Central to the play is the insistence that productions move away from the cripping-up that has dominated Richard III’s performance history by having Teenage Dick’s Richard and his actor share the same disability (in this production, hemiplegia, where in the Public production actor and character had cerebral palsy). The writing-in of the actor’s body invites a more serious and sustained reflection on living with difference than Shakespeare ever managed, drawing attention to the detail of Richard’s body and the way it works, while at the same time insisting on Richard’s right to be a complex and multifaceted individual – to be a teenage dick.

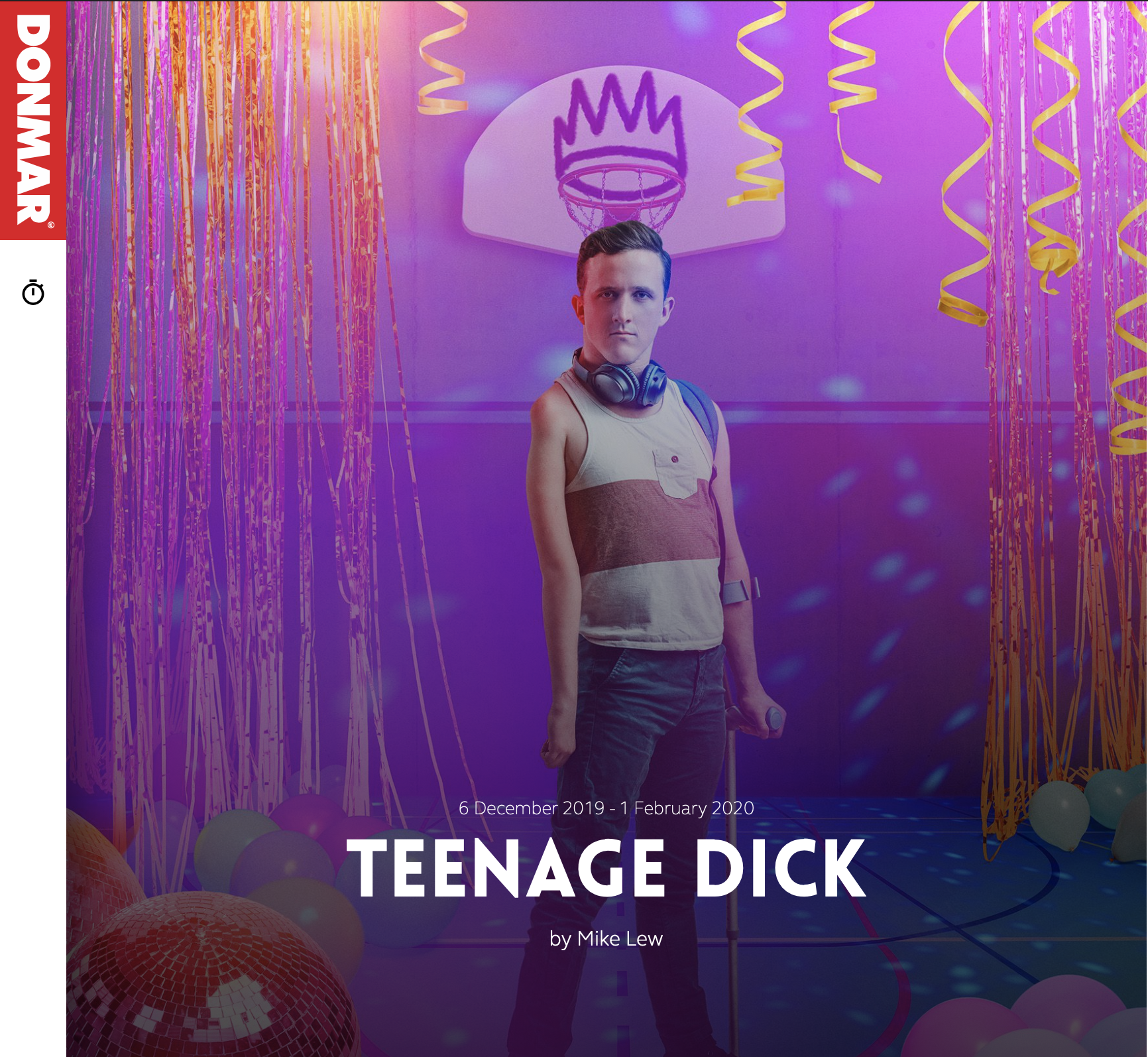

The initial tone struck by Michael Longhurst’s Donmar production was deliberately kitschy. Chloe Lamford’s spot-on set was a school gym, complete with basketball hoop and dividing nets, and the walls were plastered with banners and slogans about school spirit. Several of the characters were drawn straight from the teen movie playbook: Callum Adams’s Eddie Ivy (Edward IV, geddit?) was a jock and class president, carrying round a football and attempting withering putdowns before resorting to his firsts; Alice Hewkin, meanwhile, was hilarious as Clarissa Duke, plaid-wearing vice-president and wannabe popular girl trying to rally the freaks and geeks to her side, while objecting to learning Machiavelli because it was offensive to her Christian sensibilities. The first main scene, with hapless teacher Elizabeth York (Susan Wokoma) teaching the students Machiavelli, only to find Richard had learned the whole thing verbatim, was straight out of the teen movie playbook, establishing the characters perfectly.

But this was prefaced by an introduction to Richard (Daniel Monks), who stepped forward from the basketball nets into a spotlight to address the audience. Leaning on one crutch, and stooped under the weight of his perennial backpack, Richard raised his head to speak with knowing intelligence, bitterness, and not a little amount of self-awareness. His only ambition was to rule the school as senior class president, fuelled by years of bullying and isolation which he attributed to his disability. The careful balance that Lew’s script strikes is to make clear that Richard’s experience is real – the other kids did see and treat him differently because of his disability, with attitudes ranging from performative wokeness to discomfort to flat-out hatred, all of which positions shift with those kids’ sense of what they wanted from him – but that his gnarly hatred of others and his subsequent actions are all his own responsibility. To make Richard either saintly victim or monstrous evil would be to diminish the character.

Monks’s performance was magnetic. Speaking Lew’s words – a brilliant and hilarious heightened mixture of Shakespeare quotation, cod-Shakespeare, high-school jargon, Linklater-esque poetic wankery, and naturalistic dialogue – he established a confident relationship with the audience, waving his hand to stop and start scenes, appealing to us for support and complicity (‘Did you fucking see that?!’ after getting Siena Kelly’s Anne Margaret to invite him to the Sadie Hawkins dance), and also exposing himself. The extent to which this play requires an actor to make visible their own body and its differences to perceived norms is significant and bold, and it was fascinating to see a version of Richard becoming so vulnerable over the course of the play. Play and production worked together to manage an effective transition, beginning with flat-out high-school comedy as Richard began his underhand campaign to be class president by getting Ms York on side. Elizabeth York was quite simply the worst teacher, with an aggressive form of pedagogy and open scorn for half of her pupils, while entirely overcompensating in her deference to Richard on account of her disability, a characteristic Richard was only to happy to exploit. Pleading how difficult he found it to get around, he persuaded Ms York to cut several corners for him in getting his eligibility for the elections arranged, and these early scenes in which Richard shamelessly manipulated people set up an elaborate feint in which Richard confidently twisted people to his will with a combination of pity and emotional blackmail.

But this was a feint, as his plan to court popularity by getting together with Anne Margaret showed. Here, Anne had been the most popular girl in school but had broken up with Eddie some weeks ago, and was now keeping her head down, working on her dance training so she could get out of their small town. Richard and Anne’s first encounter, in which Richard persuaded her to invite him to the Sadie Hawkins dance through a dizzying barrage of accusations of ableism, appeals to pity, suggestions of revenge, and undermining of her own self-esteem, felt like typical Richard by this point. But as they began meeting to practice dancing, something more interesting happened. In front of the tilted mirrors that evoked a dance studio, but which also ensured that their bodies were displayed to the audience from all angles, the two began talking much more and learning about themselves. Richard’s embarrassment at being made to dance and to see himself in mirrors was real, in a way that didn’t mesh with his plans. Later, as they begun a relationship and Anne dragged him to bed, he was forced to blurt out in shame that he was wearing a diaper. Richard’s exposure of himself was matched by Anne revealing that she had recently had an abortion, and the growing intimacy and trust between the pair was appropriately messy and confused as they tried to work out what they meant to each other. And yet Richard continued to pitch this to the audience as part of his plan. The blurry line between real self-discovery and cynical manipulation was blurred even for Richard himself as his plan fell at odds with the potential for something more meaningful with Anne.

Richard’s cynicism and duplicity was also counterpointed by Barbara Buckingham (Ruth Madeley), Richard’s classmate who swooned over Eddie. As Barbara used a wheelchair, other classmates grouped them together despite their very different experiences of the world, and Barbara acted as a voice of reason and conscience, calling out Eddie on his own ableist bullshit (‘In a world of cripples, the one-legged man is king!’) and on the anger he harboured against the world, while at the same time joining forces with him to help scupper Clarissa’s campaign to be president after a horrifically patronising encounter (Buck’s face as Clarissa grabbed her wheelchair to move Buck around, and then plastered a poster onto its back, was a sight). Buck’s role as sometime-ally was a necessary reminder of Richard’s own choices and responsibility for his actions, and of the fact that experience of disability is not generalisable or homogeneous.

Inevitably, the stakes escalated as the play progressed. The ugly school debate – again, demonstrating Ms York’s total ineptitude at her job, despite her ostensibly kindly intentions towards Richard – saw the unseen masses at the mandatory school assembly cheering for Eddie like it was a pep rally, and tweeting ableist insults onto the big screen designed for questions from the audience. Richard’s attempt to run a clean campaign after making himself vulnerable to Anne led to him giving eloquent but obscure speeches from the podium while Eddie ramped up the school spirit slogans; Richard’s attempt to then humiliate Eddie in public by asking Anne to announce herself as Richard’s girlfriend in front of the school backfired horrifically. While the scenes between Richard and Anne dragged a little, their teen awkwardness and confused actions making for a sometimes uncomfortable watch, the sheer amount of time we watched them together in private paid off with this moment of public embarrassment for all involved, and Richard and Anne’s subsequent agreement that Richard would drop out of the race and they would go to the dance together without all of the politics felt like a potential resolution.

The centre-piece of the final movement was the dance itself, with a spectacular tour-de-force choreographed by Claira Vaughan. To a medley of hip-hop and classic teen rock (‘Teenage Dirtbag’!), Richard and Anne took the floor in a routine that developed visibly from Anne’s early attempts to get Richard moving in accordance with his own body. The multiple-part dance celebrated both Anne and Richard’s bodies, leaning into his disability rather than disguising it, and even integrating his crutch as part of their sequence. As with everything else in this play, it’s a performance that could only have worked with these bodies, and the sheer joy and energy of it gave it all the power of the usual teen film climax, the spectacular performance in which our heroes finally celebrate themselves on their own terms. At the performance I attended, at least, the ovation was deafening.

But thereafter, the play took a turn for the dark. Richard immediately fell into anguish and doubt, revealed as Buck told Anne to look at her Twitter feed. The walls and floor of the theatre were immediately crowded with text, as the news of Anne’s abortion (and that Eddie had forced her to have it) spread among the school as Anne frantically scrolled up and up and up through her feed. Richard’s betrayal of Anne was inevitable, his identity and drives so snarled up in his anger against the school and his lifelong unhappiness, that his self-sabotage of a possibility of happiness with Anne couldn’t stand in the way of bringing others down.

At this point, Richard finally left the stage for (I think) the only time in the whole production; house lights went on, and Anne entered carrying a bucket and her mobile phone. In a soliloquy that was both a little tonally clunky, yet still deeply affecting, Anne quietly complained that these stories were always about the men, and that this was not her story. Forced by the demands of plot, while pointing out that this should not be what was happening, she reached into the bucket and painfully smeared red blood all over her arms while recording herself, before apologising for taking up our time and running off the stage. The disruption to the flow of the play was deliberately pointed and ethically driven, refusing to have Anne die offstage or simply accept her death as character development for Richard. After such a powerful and disquieting moment, everything else happened in the shadow of Anne’s death, with Twitter immediately and fickly changing its tone to one of tragedy. In the wake of the suicide, Richard was elected class president, and his bitter, furious speech railed against the school, blaming them for her death and announcing the entire defunding of the football team in order to fund a dance studio in her honour.

The play ran out of steam in the final few moments with a sequence of bloody actions – Richard being beaten up by Eddie, and then choosing to run Eddie down in a parking lot in full view of everyone, paralysing Eddie but destroying Richard’s own future – that I felt were unnecessary; I suspect I would have found ending on Richard’s inaugural speech, with its combined sense of failure and sour triumph, more effective. But in taking Richard III in a very different direction, and with a fantastic cast nailing the combination of laugh-out-loud comedy and upsetting tragedy, Teenage Dick made a powerful case for representation both on- and off-stage, and for allowing disabled actors and characters to be seen as fully complex human beings.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply