October 6, 2015, by Peter Kirwan

MUSE OF FIRE (A Shakespeare Odyssey) on DVD

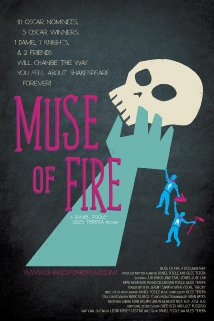

MUSE OF FIRE is an unlikely film. Two British actors, Dan Poole and Giles Terera, begin from the premise that Shakespeare is scary, offputting, difficult, and decide to ‘overcome their fears’ by undertaking a road trip taking in London, Stratford, Elsinore, Madrid, Yale and Hollywood ‘to discover everything they can about tackling Shakespeare, recognized by many as the greatest storyteller of all time’. Beginning with the everyday fears of schoolchildren and passers-by, the documentary attempts to break down fears, celebrate drama and find inspiration.

What is remarkable about this film is the ‘back door’ approach by which what feels like a home movie ends up with extraordinary access to the movers and shakers of Shakespeare performance over the last fifty years. Poole and Terera – who I’m actually going to call Dan and Giles, so charming a pair of hosts are they – are for the most part making a film about themselves. We see them wrestling with a broken down car, sharing downbeat moments over unfinished DIY projects, joking as they try to get past customs with their camera equipment. Filming their own progress, even if some of it may be staged, this film captures better than most the feeling of two blokes setting out with the simple aim of asking some questions.

And they talk to everybody. In one montage we see Dumbledore, Petunia Dursley, Snape and Voldemort all talking about how difficult they found Shakespeare in school. The publicity material advertises ‘One dame, eight knights’ and the delight they feel in securing meetings with Sir Ian or Dame Judi is captured in all its enthusiastic glory. Ian McKellen reads Juliet’s ‘Wilt thou be gone?’ and the entire ensemble choruses a series of ‘di dum’ in illustration of iambic pentameter (John Hurt is particularly hilarious as he appears to conduct the rest). To list the actors, directors and experts featured would take the length of this review. Yet what is wonderful is that the actors are open. Dan and Giles play down their own importance here, but there is a strong sense that these interviews – given in front rooms, back terraces and offices, shot off-the-cuff – are real conversations rather than soundbites. The subjects speak to actors who understand their trade and speak candidly about their fears and battles with the text, their struggles with iambic pentameter, their overconfidence when reading against their terror when coming to perform (Ewan McGregor is great in this respect).

The celebrities are the draw, but the documentary casts its net much wider. They accompany Jude Law to Elsinore and interview Danish theatregoers. They join Bruce Wall in a prison workshop in Berlin. They meet the performers of the Spanish production of Henry VIII that played during the Globe to Globe Festival and return with them to Madrid. And they celebrate the Shakespeare Schools Festival and show some lovely brief clips of children exploring Shakespeare, while also speaking offstage about how hard they find it. One of the film’s finest moments is the point where they stumble upon a small backwater American repertory theatre and chat to the artistic director, an entirely unpretentious front line ‘evangelist’ for Shakespeare working in small communities with limited resources, but in love with his vocation, reducing the directors to near-joyful tears.

The production is avowedly evangelical, and inevitably stumbles into the usual platitudes about Shakespeare’s exceptionalism that I usually work to keep out of my day-to-day life (it’s notable that the only academic featured is Harold Bloom, keeping up the Bardolatrous angle). The difference here is that everyone means it. Dan and Giles are fans, both of the people they interview (before interviewing James Earl Jones, we see them fighting with lightsabers in a bedroom) and of Shakespeare, and their own entry point (Baz Lurhmann’s Romeo + Juliet) is the same as that of so many others. The overwhelming emphasis is, despite some of the suggestions that they might answer questions, on making their audience feel that it’s okay to be scared and it’s okay to fall in love with Shakespeare. Bloom offers the kinds of unverifiable assertion about there being nothing before and nothing since Shakespeare that approaches him that one might expect; yet it is Dan and Giles’s awe at meeting a man who has devoted half a century to Shakespeare that dominates, the camera catching the quavering of Bloom’s hand as he tries to put down a pair of glasses, before moving to the views of a shop worker who saw a Shakespeare play once. Shakespeare is emotion, and the directors capture that disarmingly.

MUSE OF FIRE is a film for the fans, actors and teachers. Although at times it gestures towards how one might become enthused by Shakespeare, it isn’t at its heart about wooing newcomers. Rather, the film invites its viewers to remember how they fell in love with Shakespeare, and encourages them that it still matters. Following the climactic interview with Lurhmann, his off-camera voice encourages the two young actors to continue pursuing what they believe in, and even if the film can’t show the meat of what underpins everyone’s enthusiasm, it asserts uncompromisingly that that value is there. It’s an eighty-minute retreat, infectious in its commitment to speaking, playing with and living Shakespeare.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Illuminations DVD of the film comes with a full-length Shakespeare in Practice documentary filmed at the National which is a pleasing addition, filling in the most significant gap in the film – the plays! There is a lot of quotation, often deliberately rattled out as by one American teenager who has memorised ‘To be or not to be’, but the longer workshops allow Dan and Giles to get back into the rehearsal room with a group of actors to talk through everything from the basics (‘what is verse?’) to the specifics of particular scenes. Again, the joy here is in seeing young actors exposing their own lack of knowledge in the safety of a rehearsal room, and being in direct conversation with John Barton on Sonnet 29, for instance. This is neither masterclass nor pedagogic model; rather, it’s putting the no-fear ethos of the travelogue into professional practice, and the unfinished feel is part of that. With McKellen, Fiona Shaw and more offering commentary alongside the sessions, it’s a lovely opportunity to see behind the scenes of the development process and apply questions of rhythm and expression to close textual analysis.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply