June 4, 2013, by Peter Kirwan

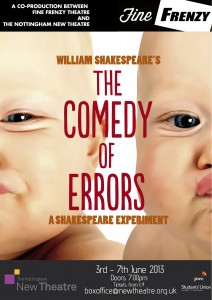

The Comedy of Errors (Fine Frenzy/New Theatre) @ The New Theatre, Nottingham

The privilege of student theatre is the freedom to experiment. Nottingham’s New Theatre, the only completely student-run theatre in the UK (and, coincidentally, the only theatre I can get to within two minutes of leaving my office) has one of the most extensive and wide-ranging programmes of classic and new writing around, and the sheer number of productions gives the opportunity for experiments such as this in a generous environment. In collaboration with Fine Frenzy Theatre (made up of recent New Theatre graduates), this new Comedy of Errors was rehearsed in 48 hours from cue scripts, evoking the spirit if not the actuality of original practices experiments at venues such as the Blackfriars in Staunton. The underpinning was less significant than the effect, however. This 75 minute Errors was a joy, a stripped-down, high-energy and self-conscious romp through Shakespeare’s unkillable comedy.

The pace was fast (a little too so at times, a small complaint regarding those moments where lines were garbled) but little of import was sacrificed – the only felt loss was the enumeration of the countries in Nell’s ‘sphere’, meaning that Jack Holden’s excellent Dromio of Syracuse abandoned this wonderful setpiece just as he was getting into his stride. Director Gus Miller’s company accelerated from a standing start – John Bell’s effete Duke showing careless pity for Greg Link’s Egeon – to a barely (but clearly) controlled chaos.

The set foregrounded the importance of play to this event. Our MC was Ben Williamson, wearing a white tiger onesie and giggling like a small child. Two free-standing blackboard doors marked the ‘Phoenix’ and the ‘Porcupine’, on which Williamson made audience members draw pictures before adding penises himself. As Link detailed Egeon’s back story, Williamson played with a toybox, pulling out toy dogs and dolls to illustrate the shipwreck to great narrative effect. More amusing, however, were his repeated vocal interruptions of an increasingly frustrated Bell and Link. The self-awareness of the production enabled the buy-in to a superficially ramshackle affair while also contributing aesthetically to the collaborative making of comedy; the audience played along with Williamson and thus with the rest of the play. The sense of the nursery was sustained throughout – bills were reckoned up on a toy abacus, money passed hands as bags of chocolate coins, and the Syracusan twins wielded lightsabers while the Ephesian twins were tied together with slinkies.

The silliness was, then, both an artistic choice and a situational inevitability, and throughout the cast referred to their own performance, most obviously in the occasional reference to the director, sitting prominently downstage in an armchair ready to prompt. As Chris Walters’s Antipholus of Syracuse was wrestled to the floor by his own Antipholus in exactly the same manner as Aaron Tej’s Ephesian Dromio had done moments earlier, he groaned ‘Not again!’, and Williamson’s Officer (credited as ‘The Strong Arm of the Law’) giggled as he was repeatedly referred to by the increasingly confused citizens.

The two sets of twins did a fine job of differentiating their characters. Walters and Sam Warren, both core members of Fine Frenzy, ensured that the Antipholi drove the plot rather than merely reacting. Walters was the smoother of the two, first shrugging as he decided to go with the flow in accepting Aemilia Gann’s Adriana’s invitation to dinner and then later advancing on Ellie Cawthorne’s Luciana with an easy charm. In his first appearance, he attempted to drag Chloe Bickford’s Citizen out on a date around town, and shrugged nonchalantly to the audience when she made her escape. Warren, meanwhile, took a particularly vehement slant on the Ephesian Antipholus, quick to anger and vicious when cornered. When tied to his Dromio, he snarled and snapped at Pinch’s assistants as he was bundled off, and entered later following his escape by wiping blood from his mouth. Warren’s finely played cad suggested a backstory of marital strife and pent-up aggression to the character that emerged the moment he was pushed.

The Dromios, meanwhile, became the physical punchbags to these aggressive masters. Holden’s Syracusan Dromio in particular dove about the stage with the sophistication of fine slapstick, and offered a confident counter to Tej’s calmer Ephesian twin. The two took the brunt of the reactive comedy, particularly in response to Gann’s finely pitched and shrill Adriana, whose dominant presence onstage made sense of both Antipholi retreating to the edges in fear. As the production grew louder and faster, the Dromios became key to keeping up the energy level, falling over themselves and keeping the fluid motion of the ever-changing stage space accelerating.

The knowing supporting performances offered several gems. Ben Hollands’s unbearably delicate Angelo guffawed his way through his scenes with both Antipholi, his laughter growing increasingly nervous and switching eventually to a high-pitched indignation as the Officer arrested him. Later, he made a point of stepping entirely out of the scene for his asides, and his artificiality transferred to the whole cast who laughed ‘heartily’ together as he took back the chain and celebrated the error. Sam Greenwood’s Merchant wore shades and a swaggering attitude that offered a beautiful foil to Hollands, and John Bell’s Pinch, in full magical robes, took a physical approach to his struggle with the Ephesian Antipholus, getting into a grapple with him and placing his hand on his victim’s head as he hollered to the heavens to extract the demon. Pinch summoned a group of white-coated lackeys to help him capture the two ‘madmen’, and Pinch stood at their head victoriously, rolling up his sleeves in preparation as he left the stage to carry out his treatment.

Emma McDonald’s West Country Courtesan was larger than life, sashaying around the stage and making the men rather hot under the collar, even the Duke whom she addressed with a knowing air. A lovely grace note at the play’s end saw her interrupt the closing music to take her jewel back from the Ephesian Antipholus, who sheepishly thanked her for his ‘entertainment’; a nice hint at a remaining question mark hanging over the production’s conclusions. By the close, though, excess was the name of the game, with even Jess Courtney’s demure Emilia throwing off her nun’s habit and a handcuffed Egeon awkwardly wrapping his forearms around her, and Pinch’s lackeys carrying out a ‘To me – to thou’ Chuckle Brothers routine as they manhandled the Ephesian twins offstage.

The finely choreographed physical comedy belied the time given to rehearsal, and Miller had clearly chosen to focus on core moments. With the Syracusan twins surrounded and nowhere to go, curtains magically opened at the back of the stage to the strains of the ‘Hallelujah Chorus’, revealing a white cross towards which the Syracusans fled. As the rest of the assembled company made to follow them, Emilia appeared in the opening, sending the pursuers tumbling back onto the stage in perfect synchronisation. Shortly after, as the twins returned, the company reacted as one in their jump of shock, which was then followed by a second shock as the twins leaped round to see one another. By this stage, the knowingness of the coincidences had taken over. The revelations were delivered in a mocking tone and the reunions laughed over communally. There was a risk, at this point, of the company’s sheer relief in making it through the play taking over and becoming cockiness, but happily they maintained discipline, with the two sets of twins in particular working hard to subtly mirror each others’ stances.

The triumph of the company in pulling together a furiously fast and funny Errors in such a short space of time shouldn’t be underestimated. While, inevitably, this had left them much less time to work on verse and nuance, the liberation of the team from unnecessary interpretive intervention or conceptualising allowed them to focus instead on the fluid dynamics, the fast spatial shuffles and the physical comedy of the play. Perhaps this, rather than the cue scripts, is the important point to take away from the experiment. That, and the fact that you don’t need to go over 75 minutes to have a great Shakespearean comedy.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply