May 13, 2013, by Peter Kirwan

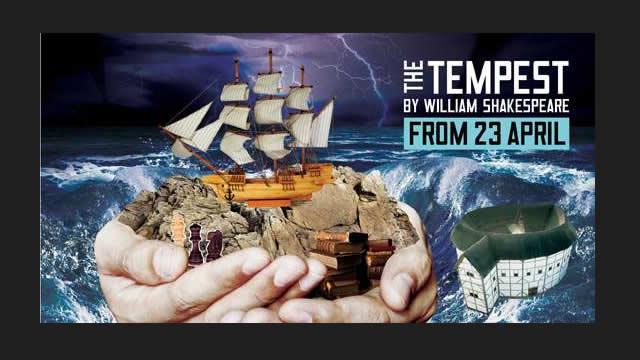

The Tempest @ Shakespeare’s Globe

My first visit to Shakespeare’s Globe was a school trip in 2000 to see Vanessa Redgrave’s Prospero in a production that is still notable among Tempests I’ve seen for many reasons, not least an ethereal, androgynous Ariel and a complete, spectacular masque with goddesses appearing on high. Jeremy Herrin’s new production was the first I have seen since that avoided overt conceptualisation and eschewed effects for language, creating a gentle and amusing, if not magical, Tempest.

Surprisingly, the highlight of this production was the romance at its heart. While Jessie Buckley was an improbably polite Miranda and Joshua James an irritatingly smug Ferdinand, the innocence of their wooing worked to the play’s advantage, making crystal clear their function as the objects of Prospero’s plans. Miranda stared wide-eyed at the ‘spirit’, diving to the floor to look him in the eyes when he knelt to her and moving towards him in smiling wonder. Ferdinand was comically deflated by Prospero who lifted his staff and waved it from side to side, sending Ferdinand flailing about the stage, propelled by an out-of-control sword, while Miranda clung to Prospero’s leg.

James’s effete performance included breaking a fingernail while carrying logs, to (slightly sarcastic) calls of sympathy from the audience. Yet following his interview with Miranda, he jollily slung a log about his shoulders and strutted offstage, head held high. The performance never allowed us to forget Ferdinand’s princely station, which in turn foregrounding the dynastic purpose at the heart of the scheme. Pip Donaghy’s blustery Gonzalo stepped forward at the end to make crystal clear the union linking Naples to Milan, and this translated to a romance that was essentially sexless, the innocently smiling couple instead being repeatedly linked by Prospero and held forth to Alonso at the end as a hope for the future.

The masque made this explicit. Ariel and two other spirits came forward in headdresses as the goddesses, delivering the speeches in formal and understated manner, but putting great emphasis (along with Prospero) on the message of waiting for sex. The masque then dissolved into dancing in which Prospero’s mission to unite the couple without letting them actually touch each other became quickly apparent. In an expertly choreographed routine, Miranda and Ariel continually drifted out of their pattern in order to try to dance with one another, while Ariel and a grumpy Prospero made it their job to yank the couple away from each other. The humour and skill involved in the couple continually interrupting the dance was hysterical, and they were finally brought together to have their hands joined by Prospero, only for him to remember suddenly the conspiracy and interrupt them once more, dismissing the spirits with a casual irritation and leaving the young lovers frustrated.

Roger Allam was a genial, avuncular Prospero, most effective when embracing Miranda spontaneously when describing her as a cherubim or cradling her head on his knee (her default position when on stage). He lacked any edge, however, with even his moments of feigned wrath coming across as humorous dismissal rather than genuine threat. Other than some sustained glaring at Antonio, Prospero had very little axe to grind, and his bellows of his abjuring of rough magic stood out as extremely odd, given the lack of range elsewhere. Allam achieved a particular reading of Prospero with skill, suggesting a man who was practical, loving and occasionally irritable, but it was a reading without particular dramatic interest, leaving him with little arc and avoiding any problematisation of his actions throughout the play.

Colin Morgan’s Ariel was similarly safe. Dressed in sequinned feathers, his performance was characterised by swinging on monkey bars and jumping off rocks, but there was no attempt to make Ariel anything more than the ‘good’ willing servant. Potential interest was set up in the character’s first appearance as Ariel seemed genuinely to have forgotten imprisonment at Sycorax’s hands, struggling to recall Algiers. A scream of memory as Prospero challenged him suggested that this spirit had somehow repressed the memories of that period, and Allam treated his recounting of the story as a sincere and impatient need to inform the servant, shedding new light on the suggestion that he had had to do this on a regular basis. Yet this hint led nowhere following this scene. Ariel remained on stage following Prospero’s snapping of his staff about his own neck, seemingly still loyal to his master.

Ariel was stronger in moments of spectacle. The supernatural was suggested by spirits running through the galleries of the Globe with instruments, creating an atmosphere throughout the theatre that gave the nobles something three-dimensional to respond to when hearing noises. The music was bizarrely upbeat and jangly throughout, however, providing a folksy and rather twee underscore that jarred with description of transcendent sounds. Better was the banquet scene, with food that suddenly lit up in flames and was left charred and unusable. Ariel entered on stilt-shoes and in feathered costume and mask, flanked by enormous wings manipulated by three spirits, and bellowed defiance at the men of sin in a deep voice that indicated the darker edges of Ariel’s power. The spectacle continued during the hounding of the clowns by skeletal puppet dogs. Disappointingly, however, the storm involved little more than some gentle Star Trek-style synchronised stumbling and a beautiful model boat disappearing among the groundlings. The actors themselves were surprisingly static for what appeared to be quite polite conversations amid the roaring of thunder sheets.

The problems of mixed tone continued throughout the clowns’ plot. James Garnon was a traditional Caliban, distinguished by his rusty red full-body make-up that aligned him with the similarly covered rocks of the set and the arrangement of his hair into short horns. I was a little uncomfortable with the wandering quasi-Caribbean accent that evoked for me the same kinds of racial stereotype that bothered me about Lenny Henry’s performance in the National’s Comedy of Errors, particularly in the tendency of Garnon to shriek during moments of stress and anger. That aside, his performance was pleasingly disgusting, spitting and burping in the audience’s faces, yet bringing urgency to his pleas with Trinculo and Stephano to follow through on the murder of Prospero.

Sam Cox was a somewhat disappointing Stephano, channelling Bill Nighy for a swaggering, stumbling performance that brought out the nascent ambition but didn’t offer a great many laughs. Trevor Fox as a Geordie Trinculo, however, provided a great foil. From wringing out his erect codpiece over an audience member’s head on his first appearance to throwing the contents of his bottle over this audience member, he milked an anarchic relationship with the audience throughout. In a brilliant gag, he withdrew to the side of the stage while Caliban and Stephano schemed, then when told to go further off, he looked into the pit, sighed, and jumped off, sounding as he did a scream that suggested he was falling miles. He later enlisted an audience member to heave him back onto the stage, on the edge of which he was clasped by Stephano and, when released, he fell back bodily into the pit to be caught by the same assistant (a plant), creating for a moment a sense of real danger. It’s the kind of risk that the production would have benefited from more broadly.

The nobles provided little independent interest, though the relationship between Jason Baughan’s Antonio and William Mannering’s Sebastian made clear the lines of influence coming from the previous usurper, Sebastian slowly growing into the plot. As the play’s action came to its conclusion, however, it became clear that the plot was about a wrapping up rather than a progression, and Allam’s severing of his staff was, excitingly, instantly followed by him seeing the audience properly for the first time. While pleasing to see a Tempest that put such attention on language and allowed more obscure aspects of the text to be played in full, this was a safe and reliable production, presenting the play without innovation but clear and rarely dull.

I’m glad someone else has noticed the flaws in Allam’s Prospero. He has a comfort zone and once he steps out of it to present fury or extreme emotion, he resorts to ‘acting’ and speechifying.

For me it was summed up when he bellowed “I have bedimmed the noontide sun”: my reaction to this was ‘No, mate. You probably haven’t.’