May 4, 2013, by Peter Kirwan

Hamlet (RSC) @ The Royal Shakespeare Theatre

Creating smallness on the stage of the Royal Shakespeare Theatre is no easy feat, but David Farr’s new production of Hamlet shrunk Stratford’s flagship theatre down to an almost nostalgic depiction of a community hall. School benches and gym bars flanked the thrust stage; fencing foils lined the walls, and a small proscenium stage marked the upstage focus. Flickering neon lights from a corrugated ceiling lit the faded motto across the archway: MENS SANA IN CORPORE SANO. Moving consciously away from the epic leanings of recent major Hamlets, Farr’s version was defiantly small, provincialising its character’s grand ideas and returning the play to its domestic focus.

This was a committed ensemble production, eschewing celebrity grandstanding or showpiece soliloquies in favour of a claustrophobic environment in which people were constantly jostling for stage space. This was perhaps most apparent in Pippa Nixon’s Ophelia, an object of silent display for much of the production: dragged in to read her own letter from Hamlet to the King and Queen; present throughout the scene with Reynaldo (distracting her father); and, most obviously, foregrounded downstage while Jonathan Slinger’s Hamlet sat upstage on the steps of the stage to deliver a low key ‘To be or not to be’. Hamlet had skipped in singing happily before seeing Ophelia, at which point his soliloquy emerged part as manipulative performance, part as exhausted expression, flowing naturally as the fear of dreams occurred to him.

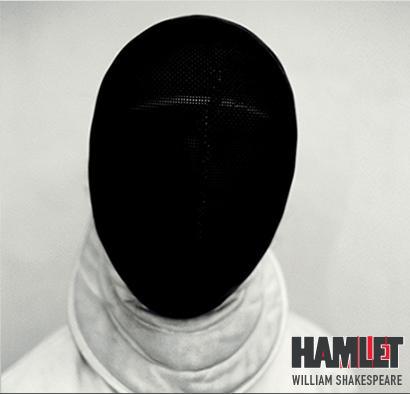

Part of the extended representation of community in this production was the sense of a cast sheltering from the cold, Denmark becoming not so much a prison as a too-small refuge. While Greg Hicks’s Claudius wore a three-piece suit and organised formals in the hall (masquers wearing fencing face guards), this was a world of woolly jumpers (including the matching ones worn by Ophelia and Alex Waldmann’s Horatio) that evoked the recent trend for Scandinavian crime dramas. Yet in this small world where everyone knew everybody else, a sense of the local predominated, and lines connecting this world, particularly Hamlet’s genuinely moved address to Yorick’s skull, were emphasised.

The fencing motif moved from the hobby that was the main focus of this community hall to the cut-and-thrust politics that drove the play’s second half. Hicks, doubling as the Ghost, appeared in full gear, linking his own death to that of his son’s. The anonymising masks of fencers recurred throughout, both serving to mask Hamlet himself at moments of his feigned madness, but also providing an iconic aspect to the final duel.

Slinger was a fascinating Hamlet, strongest in his moments of humour whether bantering and rutting joyfully with the newly arrived Rosencrantz and Guildenstern or mocking Claudius in his attempts to find Polonius, with a matter-of-fact deflation of formality. Slinger’s strength as an actor beyond the comic is his vocal range, however, and his transition between the lower register that marked lines such as ‘except my life’ and the fast, almost giggly tone of his public speech finely illustrated the character’s multiplicity and levels of performativity. Finely controlled, except for a rage-filled outburst during ‘How all occasions…’, this reflective but emotional Hamlet was conscious of a world falling apart around him.

In this, Ophelia became central. Not only onstage for much more of the play than is usual, Nixon’s Ophelia had an independent strength that belied the fact that the men around her spoke about her dismissively, barely acknowledging her if at all. Summoned and sent away at the click of her father’s fingers, her own views were rarely requested. Poignantly, Charlotte Cornwell’s Gertrude was appalled to hear that Polonius had warned his daughter away from Hamlet, and held out a hand towards the girl as she was sent away. Later, Ophelia went through the motions of presenting a remembrance box to Hamlet, but clawed in horror at the remains after he overturned the box. Hamlet’s aggression towards her in the nunnery scene included stripping her of her upper layers, leaving her exposed and vulnerable, before he covered her in what appeared to be ink and abandoned her. Later, she was momentarily brought in to hear the news that Hamlet had killed her father, crying out before being escorted away.

During the second half, Fortinbras’s army cleared away the flooring of the hall to reveal an underlayer of soil and part-exposed bones, and the back wall was removed to show a wintry landscape and blasted tree, the exterior and skeletal world that these characters inhabited. Against this backdrop, Ophelia’s mad scenes looked extraordinary. Clad in wedding dress, this Miss Havisham figure was aware on some level that there was to be no marriage, but went through the motions, imagining her father giving her away, encouraging the ‘guests’ to sit and shrieking excitedly in Gertrude’s direction. The close relationship between her and Horatio saw the latter looking after her in these scenes, escorting her gently on and offstage. For her funeral, a shallow grave was dug in the soil, in which she lay for the remainder of the play (an impressive act of endurance, especially with a duel going on around her). Nixon’s Ophelia became a focus for everything that happened between Hamlet and Luke Norris’s earnest Laertes. Hamlet’s cry of grief that he loved her was one of the play’s highlights, a cry of desperate honesty that cut through, and as he died he staggered towards her, his final ‘Ohs’ becoming smiling sobs of recognition. He was thwarted, however, the convulsions of the poison finally turning him away from the body of his love to die alone on the fencing platform above the soil.

The rest of the supporting cast were efficient, with Robin Soans especially effective as Polonius, controlling his children yet not over-egging the ridiculousness of the character. His emphasis on finding out directions by indirection was lingered on, pointing to the connection to Hamlet’s own methodology, and his apparent carelessness of his daughter was explained in his absolute devotion to his king. Hicks and Cornwell as the King and Queen were affectionate with one another, though Gertrude was accorded several glances at the audience during Claudius’s patronising attempts to reassure her about her son. Hicks was a surprisingly insecure Claudius, a showman who forced Hamlet to down a glass of wine in celebration and who was eager to be liked. His increasingly frantic attempts to protect himself in the second half began an unravelling which culminated in the fencing match. Gertrude quietly refused to put the drink aside, and Claudius himself was forced by Hamlet to take his own poison, Hamlet sitting on the stage and waiting patiently for Claudius to reenact the drinking game with which their stage relationship had begun.

The theatricals and game-playing of this court were best represented in a fabulous The Mousetrap. The hilarious dumb-show featured characters wearing pieces of bread standing for phallus and breasts, and the king a towering crown which he struggled to uphold. The low farce and sexual aggression of this piece (culminating in a vamp playing ‘Poison’ coming in to the sounds of thrash guitar and straddling the sleeping victim’s head) were replaced by a sober, faux-naturalistic scene of a queen dressed identically to Gertrude and a usurper wearing the same suit as Claudius, making explicit the connections that caused Claudius to end the play. The ensuring frantic action saw Claudius’s heavies aggressively drive the players from the hall, even as Hamlet and Horatio celebrated their findings.

But the play’s heart was in its smaller scenes, and the chilly environment of the graveyard in particular. The two gravediggers were genuinely hysterical, with David Fielder’s First Gravedigger sitting genially with Hamlet and talking him through the rotting of skins. While Horatio did not feel central to this version, it was Waldmann’s performance that perhaps best anchored Slinger’s, the quietness of their scenes together (even when mocking Michael Grady-Hill’s overly enthusiastic Osric) perfectly conveyed the friendship bond that warmed the cool surroundings. Amid the poetry, the politics and the violence, these connections recurred insistently, suggesting a warmth lost in the final moments as leaks sprang in the ceiling of the community hall, an evacuation bell began ringing and the silhouetted figure of Fortinbras appeared upstage. This Hamlet was not about the death of a prince, but the destruction of a community, with no sense of what (if anything) would replace it.

[…] Miss Havisham (the second time I have had cause to reference this character in a production this weekend), floated about the stage humming to the sound of Jen Waghorn’s violin. As the jilted […]

[…] in repertory with Hamlet, Maria Aberg’s new production of As You Like It shared more than just a company that […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here: blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/bardathon/2013/05/04/hamlet-rsc-the-royal-shakespeare-theatre/ […]