May 29, 2012, by Peter Kirwan

The Merchant of Venice (Habima) @ Shakespeare’s Globe. Part 1: Outer Frame

Reviewing an event such as this evening’s performance at the Globe of The Merchant of Venice by Habima (Israel’s national theatre) poses serious ethical questions. If the review focuses on the entire experience – the preliminaries, the tensions, the various kinds of performance taking place both outside and within the auditorium – then the production itself, Habima’s work, risks being sidelined. If, however, the review ignores the “outer frame” (as Susan Bennett might term it) and concentrates on the “main event”, what was intended to be seen, then it is compromised in two ways. Firstly, the experience of every audience member was shaped and formed by the extraordinary framing of the production, that was inseparable both in terms of the mindset with which we entered the Globe, and in terms of how interwoven the subsequent acts were with the main performance. Secondly, in ignoring the elements that were not legitimised or planned for, I would be colluding in the silencing of a protest that, whatever you might think about it, had important things to say and deserves to be reported.

This review, then, will be of unusual length. It is subjective, as all reviews are, but it is unashamedly so. It is also political, if only insofar as I support the right to protest and the right to express views peacefully. I did not participate in any of the protests this evening, either in the pro-Israel camp or among the Free Palestine lobby; it’s a situation which I choose not to actively campaign in. Nor, however, did I participate (as did many of my fellow audience members, with that self-righteous, zealous passive aggression that only late trains, queue jumpers and people who talk at the “wrong time” draw out of the British) in the active silencing and removal of the protesters. The heavy-handedness of the policing of tonight’s performance was at least as disruptive as the mostly silent protests themselves, and I have never been in a theatrical situation where I have felt more intimidated, watched and surrounded by hate. And for the most part, that wasn’t coming from the protesters. This part will deal with the framing, and I’ll focus on the performance itself in a follow-up tomorrow.

I spent the day on the South Bank, where a heavy police and private security presence began to make itself felt from 4pm. At 4.30pm I found myself locked inside the Globe building during an apparent incident, which meant no-one was allowed in or out for some fifteen minutes. Shortly after, the Globe was cleared of all members of the public for a full security sweep (my thanks to an amusing and welcoming duty manager, who was a relief to deal with after the frankly extremely rude security team). Outside, crowd control barriers were being set up and the South Bank rearranged, heavily policed, to contain the anticipated protests.

Security barriers set up on Bankside

Heavy disruption had been expected around Habima’s performances since they were announced. The company, I understand, has performed in occupied areas of Gaza, and is seen by many as a tool of the Israeli regime. I defer to those more knowledgeable than me to debate the rights and wrongs of the company’s actions; fundamentally, though, I had no desire to see the production boycotted. Does the Globe’s invitation legitimise an institution that assists in an illegal occupation? Very possibly; but its presence on the South Bank both gave a voice to Hebrew-language theatre and, more importantly, legitimised a peaceful protest. As the two lobbies gathered in cordoned-off areas on the South Bank, I collected a wide range of literature arguing for and against the right of these artists to perform to a London audience. In the context of a Festival such as Globe to Globe, there appears to me to be a solid argument for the value of debate; a debate which the production’s presence allowed to happen. Or, at least, should have.

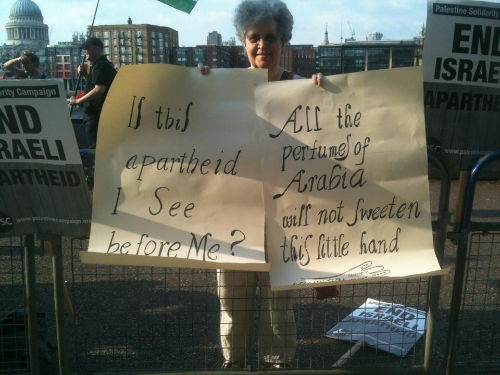

Protesters in the Palestinian camp

The protests on both sides were deeply felt and heated, perhaps unsurprisingly for a particularly hot May afternoon, but largely peaceful. Tempers frayed, however, during the bag checks, which began an hour and a half ahead of performance time. Information had been sent out to all ticketholders in advance to let us know that we would have to check all bags bigger than a handbag, and that none of our own food, drinks or anything that could be used to disrupt a performance would be allowed in. Full security gates were in place including metal detectors and pat-downs, and several of my fellow theatregoers argued strongly with the beleaguered security folk about their right to take in their own sandwiches. The fact that, inside, the Globe was charging £2 for a can of Coke and £1.50 for a bottle of water stung a little.

Protests in the pro-Israel camp

Relieved of bags, the Globe audience then had to cope being cooped up in rather too small a space for an hour until the doors opened. We were entertained during this time by the impressive human beatbox duo Sweet Combination, who sang and played at a volume significant enough to drown out any distant protest noise – although one group did manage to get a loudspeaker onto the Bankside pier to cause a little disruption. The heavy security presence remained somewhat intimidating, particularly in such close quarters, so it was a relief for doors to open and the crowd to spread out inside the theatre.

The last key element of framing came once the house was full and doors closed. Dominic Dromgoole emerged to welcome the audience. The very fact, of course, of the Artistic Director of the Globe coming out to address the crowd in person spoke to the unusual nature of this event, and for the most part he dealt with it appropriately and in good humour, hoping that we approved of the new front of house arrangements and welcoming us to the performance. However, I found myself troubled by some of the ways in which he framed the expectations for the evening. The Globe is used to dealing with disturbances, he said – pigeons, fainting, planes – and he asked the audience not to take it into its own hands to deal with any disturbances during this performance, as Security would do so. The security presence inside the theatre was exceptional, surrounding the stage itself, spread through the pit, and standing in almost every gangway in the galleries. To reduce the disruption of protesters pre-emptively to the accidental/occasional disruption of a pigeon was a rhetorical strategy I found unnecessarily demeaning.

The new front of house arrangements (metal detectors and bag checks)

Dromgoole rightly pointed out that the actors onstage were neither politicians nor policy makers, to the approval of most of the crowd, and pointed out that anyone who disrupted the performance – or whose phone went off, an announcement delivered with emphatic glee – would be immediately evicted; but he asked the audience not to engage in any vigilantism. It’s a safety caution that was important to make, and I was extremely pleased he asked the audience to ignore rather than confront protests; implicitly leaving interpretation to the individual spectator. These were artists telling a story, Dromgoole informed us, aiming to understand and to criticise, and to help make the world a better place. Now, however, while I can’t take issue with these sentiments, I found the appeal to a “better place” difficult to stomach coming from a man standing on a stage with the backing of a good fifty huge security attendants ready to evict anyone who disagreed or dared to disrupt. Whether or not the theatre is the appropriate place for this kind of protest became irrelevant for a moment; the heavy-handedness of the policing, and the gentle mockery which served to bind together an audience in derision of the Palestinian protesters, came across to me as a gesture of control and display of power that quashed any hope I had of a “better world”.

I’ll go on to the performance itself in a separate post, but I’ll deal with the protests here. About five minutes into the performance, banners and flags were unfurled in the galleries, and security acted quickly to remove the women displaying them. This was followed by a silent protest – a group stood to attention in the first gallery for the entire first half, masking tape over their mouths, presumably protesting at the silencing of the Palestinian voice. I was surprised to see this group left alone – they were non-disruptive, but so were the earlier flags; and actually, one woman in particular appeared to be obstructing the view of the person behind her, which on any other day would be cause for a steward’s intervention. Towards the end of the first half, following Bassanio’s success in the casket challenge, a younger group began unfurling banners in the pit and protested noisily when evicted. By this point, however, the rest of the audience seemed to be losing patience, and civilians began taking a turn at pointing out protesters to security and ordering them to shut up. This policing of the pit I found one of the most upsetting aspects of the evening; the audience turning in on itself over a question of etiquette, but with displays of aggression from the non-protesters that I found disheartening; security were quick to respond, but audience members felt the need to actively participate in shutting down the (silent) voices of the Palestinian protesters and, apparently, take satisfaction in being seen to do so.

The second half was much less disrupted, but more vocally when it was. During the trial scene, a gentleman standing next to me with an extraordinarily clear voice called out “Hath not a Palestinian eyes?”, and was followed by another. They left with very little trouble as soon as Security identified them and touched their arms, although I had the impression there was a little resistance. Obviously, the consciously disruptive nature of this form of protest made it more of an issue (within the conventions of British theatre etiquette) than the silent protests of the first half. However, the aggression of the audience towards this more deliberately disruptive incident was, again, perhaps even more unsettling. An angry cry of “Piss off!” was met by laughter – laughter – from around the theatre, as audience members joined in the jeering of the protesters as they were evicted. More encouragingly, one man shouted out to the flustered actors “We’re with you, keep going”. The support of the audience for the actors was encouraging; the bile displayed towards the protesters less so. As I was standing next to the men who shouted out, I felt the eyes of the audience on me, found myself at the business end of a dozen pointed fingers, and experienced something of the hostility directed at those who believe in something strongly enough that they feel the need to say it out loud.

When the performance ended, and we finally got through an initially badly organised bag reclaim procedure, the South Bank was still full of police. One group (silent when I saw them) was surrounded by police in a miniature kettle; while another woman screamed out about apartheid to the departing theatregoers.

I don’t like theatre to be disrupted. I dislike whispering, phones going off, antisocial reactions; it goes against the conventions I’ve been brought up in as a theatregoer – though to expect these in the Globe at any time is to fight a losing battle. But I’m an advocate of free speech and peaceful protest; and apart from the shouts during the trial scene, the protests outside and within the Globe space were largely silent and visual until removals began. I have never felt quite so intimidated, tense and uncomfortable at the behaviour of people around me as I did tonight at the Globe, and it was the aggressive interventions of the non-protesters rather than the protests themselves that prompted most of these feelings. The presence of such a system for controlling the reception for the production was such that, whether or not a protest had actually taken place, the presence of that which was being silenced was assumed. I am pleased for the sake of Habima that the disruption was minimal; I am glad that I had a chance to see this production. I just wish that the openness, freedom and generosity that have characterised so much of this particular set of cultural exchanges could have been more evident tonight on both sides.

A very sensitive commentary on a very important issue. I applaud your empathy and your insights into the outer frame and on the police state context in which the entire event occurred.

As an eyewitness account, this is a valuable post, and the images are fascinating; I’ve emailed the link to several people interested in the circumstances of this production. I’m glad to have a well-written review to read; knowing you helps me to imagine what it was like. This is, as several people have said on Facebook, an important post. Thank you very much for writing it.

I’m not sure that we can absolve ourselves of the responsibility to be as knowledgeable about Habima’s activities as the people to whom you defer. Not if we intend to see the production and write about the political atmosphere under a personal aegis. Ten years ago, I’d have agreed that it was possible to separate performance from production (and, indeed, I think it’s wholly understandable that you’ve done so in a blog format, where attention spans are so much shorter – you’re always very readable), but now I don’t think it is.

I don’t actively campaign on the Israeli/Palestinian issue on a regular basis (I don’t actively campaign enough full stop), but I know my views and can explain them, and they would affect my behaviour with regards to a production like this. I am leaving it at that ONLY because I don’t want to get into a big Israel/Palestine debate in the first instance, and because my issue is actually less the maintenance of opposing views than whether we have the right to not take a view while benefitting from a production – as audience members, as reviewers, as self-bloggers, as readers of this blog.

Everyone has the right not to hold or express a view on an issue, but I find the combination of content created from the politically-charged material from the protests (this + your prose style is what gives the post its value) + a kind of neutral stance problematic. It’s difficult to negotiate the point at which sensitivity tips into evasion. It feels like a kind of tourism – which, of course, is part of what the Globe does (and does best; a meeting-house for international experiences of theatre). But I feel that to attempt neutrality + absolve oneself of the responsibility to know about Habima, to take a stance one way or the other is to let yourself off the hook a bit too easily.

Especially when this production did not allow debate; nor do I think that the production exactly “legitmised a peaceful protest”. I think protests of that sort and scale (on either side of the issue) are always legitimate. The production caused the protest by being, in the views of many, inherently immoral (but obviously you know that). Partly I am just thinking out loud, and I do have a better-informed friend, an actor and activist whom I know has been corresponding with the Globe on this issue (so, yes, I appreciate the need to acknowledge when others are better-informed, once we’ve educated ourselves). I’m hoping he’ll add his voice to the conversation – you know, the conversation the Globe didn’t want to have.

I end this with the disclaimer that I do have great, personal, ongoing respect for the work of the Globe (and indeed for you + your writing!). It’s greater than my misgivings about this production and what you tell me about its framing. I do think it’s a shame; I wonder how it’ll be viewed 20, even 50 years hence.

The Globe to Globe season includes companies from countries (Albania, China, Georgia, Serbia, Pakistan, Russia, – to name a few) with far worse human rights records than Israel. To single out the Jewish cast of the Merchant of Venice for special treatment is an act of racist bigotry – and especially ironic, in view of the content of the play.

A fascinating review, which confirms to me what I had been suspecting about London in the year of the Olympics and the Jubilee. I think it’s particularly valuable that you air your concerns, not as a ‘radical’ or ‘anarchist’ (I don’t mean that I support those terms; I use them ironically), but as an ordinary theatre-goer who is reflecting on his experience.

But I wonder whether there is something problematic about your own position? My concern is over the discourse that you occasionally use – ‘legitimised a peaceful protest,’ ‘there appears to me to be a solid argument for the value of debate,’ ‘I’m an advocate of free speech and peaceful protest’ – which is the language of various news outlets that we can all think of; and it’s a discourse which has a very clear ideological function, which is (paradoxically) to stop debate in its tracks. The student protests, the Occupy movement… so often, when these things are reported on TV, the presenter reports (some of) the basic facts then moves quickly to say something like ‘This all raises the question of free speech,’ and then about five people discuss this ‘question’ for ten minutes, before the next news item comes. And this is done so that the actual issues don’t have to be engaged: one can report on, say, Occupy, without actually mentioning it; one just debates abstractly about whether or not protest is a good idea, whether or not people have a ‘right’ to do it. And this is deliberate… it’s a way of avoiding serious issues; a potential political debate is diffused, and a simulacrum takes its place.

So I think that we should be incredibly careful when we start talking like this, because the danger is that we will just neutralize the arguments, and move into abstract territory (though of course this territory is already heavily politicized, which can be seen in the fact, for example, that ‘peaceful protest’ is extolled, but violent protest isn’t; why?). There’s the danger that one’s attempt at, to use Sophie’s superb phrase (above), ‘the maintenance of opposing views’ will stop one actually listening to these views, stop one taking them seriously. I know that you haven’t done this, that you’ve read around… I just mean that the discourse that you make use of is ideologically loaded, and inevitably pushes the discussion in this direction.

I know that this isn’t very clear. If I was to summarise my position in a crass way, I would say something like this: we have two sides of an argument (Israeli, Palestinian); both of them no doubt have sense and truth on their side, though I think more on one than the other; and our response should be to (as you do) read up on the issue, come to a conclusion on it. What I don’t think we should do is fetishize the disagreement, so we make our aim not its resolution but instead the possibility of its articulation; we shouldn’t allow the disagreement to become valuable in itself – because we like ‘free speech,’ appreciate ‘the value of debate,’ and so forth. The problem with this stance is that it can seduce us to a position of intellectual and moral superiority, when we ourselves are not actually engaging with the problems in any serious way. The police use batons to shut down the Palestinians, but we can shut them down by reporting the fact of their protest, but not reporting the reasons for it, the validity of those reasons, counter-arguments, and so forth. Instead, the protest is used as a theme which gives rise to a set of intellectual variations – on why ‘debate’ is good, why ‘peaceful protest’ should be legitimized… all of which is very nice and worth saying, but it neutralizes the important issues, re-packages them in a less disturbing form.

I just mean that we should be aware of what we are doing, and of the dangers of this sort of writing. But I did find this article valuable, and it’s worth other people reading and thinking about seriously.

From Dave Paxton’s comment:

_And this is done so that the actual issues don’t have to be engaged: one can report on, say, Occupy, without actually mentioning it; one just debates abstractly about whether or not protest is a good idea, whether or not people have a ‘right’ to do it. And this is deliberate… it’s a way of avoiding serious issues; a potential political debate is diffused, and a simulacrum takes its place.

So I think that we should be incredibly careful when we start talking like this, because the danger is that we will just neutralize the arguments, and move into abstract territory (though of course this territory is already heavily politicized, which can be seen in the fact, for example, that ‘peaceful protest’ is extolled, but violent protest isn’t; why?). There’s the danger that one’s attempt at, to use Sophie’s superb phrase (above), ‘the maintenance of opposing views’ will stop one actually listening to these views, stop one taking them seriously. I know that you haven’t done this, that you’ve read around… I just mean that the discourse that you make use of is ideologically loaded, and inevitably pushes the discussion in this direction._

This, absolutely – this better articulates my discomfort (also thanks for the compliment, Dave).

To Ian: working in a state, and backing it are not the same thing. In my opinion, the Globe should not invite (and thus fund) theatre companies which support oppressive regimes. I think Habima as an organisation (I can’t speak for the politics of individual actors) does this. See also: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/mar/29/dismay-globe-invitation-israeli-theatre (with thanks to James Ivens).

Thank you all for your comments so far, and for the generous tone.

Sophie and Dave – thank you for your insights and warnings. I think you’re extremely right about the dangers of this kind of reportage, and I do not hold up this blog as a model of how this kind of event should be reported. It wasn’t an easy one to write; and the thing I will say for it is that it’s honestly reflective of my experience.

I am intrigued that the post was read as neutral. That wasn’t my intention, and it’s not something I would strive towards. What I confess, with some embarrassment but absolute honesty, is that the Israel-Palestine conflict is not an issue I feel enormously well informed on, and for me to pretend or artificially create an active investment would be hypocritical. Events such as this are spurs for me to learn more and invest more (and in my defence, there are other political situations that I DO feel very strongly about and campaign on; we all have our own particular focuses). Dave – if the protest seems fetishised, that’s an issue. However, I didn’t have the ability to converse with any of the active protesters within the theatre, and as they were unable to use words, it is difficult to engage other than to report honestly their performance of protest. I collected a great deal of literature before the show from both camps, however, which I’m digesting.

I think it is important to note that an extreme stance either way on the conflict was not a prerequisite for buying a ticket to the show; it’s an experience which people had to encounter whether they wanted to or not, whether they were informed or not. I’m writing as someone broadly sympathetic to the Palestinian protests but uninformed about Habima’s particular role in the occupation, and whose authority is as a Shakespeare scholar and performance critic; and as such I am pleased that you’ve found this account useful. Sophie and Dave – I think your criticisms are important and I am pleased to be pulled up on them, but would be even more relevant if I was striving after neutrality and considering this review an “end point”. I hope that I am doing the reverse, and documenting this experience as part of my own education and politicisation in respect of an issue I should be more invested in.

As one of the Free Palestine protesters outside the theatre, and the co-founder of British Writers in Support of Palestine (www.bwisp.wordpress.com) I would first like to thank you for this detailed account of your experience, which corroborates the experience of the in-house protesters I spoke to, and counters already distorted reports in the media that the eventual shouting and aggression began with them. According to my eyewitness reports, the one man who was arrested, was being carried out when his flailing arms hit a security guard in the chin. For this he was arrested on suspicion of assault.

I must however, agree with Sophie and Dave, and add that hopefully the protest will encourage you to think more deeply about the issue of Habima’s illegal behavior. To start with they do not perform in Gaza – the last Israeli settlers were evicted from Gaza in 2005, and since then the territory has been under an inhuman siege. Israel does not allow in building supplies, or even enough food – they have actually calculated the calorific needs of the population, and allow in less than is necessary for good health. One official called it ‘putting the Palestinians on a diet’. (http://www.medialens.org/alerts/10/101117_put_the_palestinians.php) It is almost impossible for people to enter or leave Gaza, and certainly the long-suffering inhabitants would not be interested in performances by the Israeli National Theatre. Habima perform to Jewish-only audiences in the settlement of Ariel, which is located deep within the West Bank, far behind the ‘green line’ (the 1967 borders which theoretically still form the basis of a future two state solution). To transfer citizens into occupied territories is illegal under the Geneva Convention. By entertaining settlers, Habima is helping to legitimize and consolidate Israel’s on-going acts of land theft and ethnic cleansing – acts that make peace with Palestine a very distant possibility. Illegal behavior on this epic scale ought to be punished, not rewarded by prestigious invitations to perform in one of London’s greatest venues.

The cultural boycott of Israel has nothing to do with ethnicity, and everything to do with international law. It is also a response to a specific, comprehensive organised call from the Palestinians, calling for Israeli to be subjected to a international campaign of Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS). (www.bdsmovement.net / http://www.pacbi.org) Responding to this call transforms an act of individual conscience into an act of genuine solidarity. Such organised calls are not yet being issued from the oppressed people of the nations Ian mentions. But if the pressure BDS exerts on Israel is successful – as it was in the case of South Africa – then global boycott may become a powerful, non-violent tool in the struggle against oppression in other countries.

Thank you again for taking the protest so seriously. In the West Bank peaceful protests are met with tear gas and bulldozers and too often result in the injury or even death of protesters. I respectfully ask you to consider your own experience in that even larger frame, and to reconsider your views on cultural boycott as an appropriate response to such serious injustice.

Peter – just read your comment. Thanks for reading the protest literature, and for taking the time to educate yourself more deeply on the conflict and the issues it raises.

Thanks for writing this piece, it is clear and thoughtful.

I was one of the British artists calling for the disinvitation of Habima. While of course I would have preferred that you join the boycott, your view from within is interesting and valuable.

I’d like to make a few clarifying points on what you’ve written here.

Firstly, I would heartily endorse a Hebrew-language or Israeli national inclusion in festivals such as this. I and others only found the invitation of this specific institution, with its recent history of collusion in human rights abuses, unacceptable.

Secondly, I don’t entirely agree that inviting Habima was justified because it facilitated debate. That could have been better facilitated by inviting an alternative group and prompting the question, “why not Israel’s national theatre?” This would have enabled discussion without compromising the policy of inclusiveness that Habima’s activities have undermined.

Finally, I was saddened to read your report of the attitude of Globe management and spectators. While I imagine it was by no means uniform, such pompous sneering at activists is commonplace in a certain layer of society. Unfortunately history demonstrates there is little hope of changing this. It is the mass of ordinary artists and workers – those at the sharp end, who have no patience with the jeers of the privileged – who must be looked to. We are the force with the reason and power to stand up for artistic freedom and the rights of all peoples.

I was at the Globe yesterday, not inside but participating in the anti-Habima/pro-Palestinian demonstration. More to the point of this message, I was one member of a small delegation that went some months ago to talk to Globe Artistic Director Dominic Dromgoole, and the director of the Globe-to-Globe festival Tom Bird. The discussion was civilised and engaged: our only beef against them was that the invitation to Habima had been issued, not that they were eveil men. Of course we asked for the invitation to Habima to be withdrawn, and of course they declined to do so. But arising out of that conversation we made 3 (we thought) constructive suggestions::

i) that the Globe should make the maintenance of the invitation conditional on Habima issuing a statement that they would cease giving performances in the illegal settlements

ii) that we should prepare a statement (agreed between us and the Globe) to go as an insert in the programme, explaining to the audience why having Habima at the Festival was so deeply problematic

iii) that ahead of the Festival the Globe should stage a public debate, with the sort of high quality contributors they would be able to attract, on the general question of the reasons for and legitimacy of cultural boycott.

Dominic Dromgoole in the end declined to take up any of these 3 options, any one of which might have helped to ease the tense situation at these performances. Learning the lesson of this failure (a failure of nerve?), isn’t now the time to stage that public debate we asked for? Perhaps not at the Globe, though. It is doubtful that it would now have the moral authority to act as an appropriate and neutral honest broker.

Which other productions were attacked by a dedicated group? Is it to be understood that Israel is the worst offender against human rights or only the smallest and the most publicised? In what way is the PA morally superior to Israel, ditto China.

If activists are there to change things I would like to see a great many more of them protesting against many more abuses

Ray:

You ask – “In what way is the PA morally superior to Israel, ditto China”. First of all you have to understand that the term “morally superior” applies primarily to the politically-correct progressives in Britain, a status (self-proclaimed) that gives them the inalienable right to pass moral judgement on everyone else. They apparently have standards and criteria which enable them to rank the offenders, none of which can be easily understand by mere mortals like you and me. If these “chosen” were from Sweden, I might have some respect for their views, but seeing that they are from Britain (no offense), and after reading about the never-ending atrocities against civilians in Afghanistan, for example, one wonders exactly why they have earned this moral superiority. But once one conditions oneself to ignore or mask ones own atrocities (as the Guardian neatly says: “US led NATO forces”) it really isn’t difficult to selectively ignore others, whether it be the destruction of Grozny, the occupation of Cyprus or the Han settlers in Tibet, none of which are deemed sufficient to arouse a protest by the morally-superior chosen. Of course we will soon see a string of comments “explaining” to us what the “difference” is, and I must admit that I greatly admire this ability to create an endless stream of totally irrelevant “differences” with such ease.

Ray – many states share with Israel an appalling record of human rights abuses and boycott could be an effective tactic against other places.

However the boycott of Israeli institutions was called for by Palestinian civil society and it is in response to this call that the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement is growing. It is not a question of moral superiority rather a case of demanding that Israel be held to account for its violations of international law. Yes, Israel is small but in terms of human rights abuses it punches above its weight. Israel has controlled the West Bank, the Golan Heights and Gaza for almost 45 years, over 2/3 of its existence. What action would you suggest as an effective method to change the current situation?

Janet:

” the boycott of Israeli institutions was called for by Palestinian civil society”. And if Palestinian civil society asked you tomorrow to become a suicide bomber would you automatically comply or do you have a mind of your own ? Are you saying that the Chechen, Cypriot and Tibetan civil societies have not asked for a boycott of Russia, Turkey and China, respectively ?

http://www.etters.net/Tibet.htm

So why wasn’t everyone boycotting the Chinese theatre at this festival.

“Israel is small but in terms of human rights abuses it punches above its weight”. Exactly how have you quantified this ? (refer to my previous comment).

“Israel has controlled the West Bank, the Golan Heights and Gaza for almost 45 years”. Britain has controlled parts of Ireland for over 800 years and currently maintains Apartheid walls in Belfast. What action would you suggest as an effective method to change the current situation? Should I boycott British theatre ?

Commenters may wish to see the second half of this review, focusing on the production itself, now posted at http://blogs.warwick.ac.uk/pkirwan/entry/the_merchant_of_1_2_3_4_5_6/ .

Naomi – thank you for your correction on my Gaza/West Bank confusion.

1. There is no Palestine. It ceased to exist on 14th May 1948 when the British left it.

2. Israel owns the Western Bank following the war declared upon it by Jordan, Egypt and Syria in 1967. When you declare ware and lose – you lose land.Germany was so divided for more than 40 years.

3. Anti-Israeli expressions by Europeans, who do not live in the Middle East, are merely modern day expressions of anti-Semitism. Thank G-d, we have a Jewish state that an protect us.

Yes, there was a counter-demo. For the truth about the link between the British Zionist Federation and the neo-facist English Defence League click here:

http://hoffmanchronicled.wordpress.com/the-zionist-federationedl-alliance/

Since the links don’t work, google Hoffman Chronicled.

JanetGreen I would suggest that the Palestinians sue for peace. I cannot understand why they on the one hand complain how hard things are for them and on the other complacently reject negotiation

This is a very sensitive review but it tackles the outerframe without penetrating to the core. Habimah has performed in the settlements of the West Bank and Ariel in particular. They are not neutral and it sickens me when people say culture and politics don’t mix. Hitler funded the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and Furtwangler, its conductor, to present the ‘nice’ side of Germany. Oh, you may say. That’s different – well it wasn’t then. Lots of establishment people went to Germany and said how it had been misportrayed and they continued to do that until Krystal nacht forced them off the fence.

I was one of the protestors last night and I was violently evicted. I am also Jewish and I would be happy for a Yiddish (the real Hebrew culture of the diaspora) play to be performed or one in Hebrew but not one that represents Israeli settler colonialism.

Those who cannot defend Israel’s practices say ‘what about…’ This was the same argument of Apartheid’s defenders. The Tibetans are not asking for a boycott nor are the Iranians and Syrians. It is a selective weapon used mainly against a homogenous population that dispossesses and terrorises another. South Africa, Germany and now Israel. Palestinians ask for it and we should respond.

There was a real victory for the Cultural Boycott last night. Israeli ‘culture’ (funded incidentally by specific grants to touring companies whose message is in harmony with Brand Israel) can only take place under lock-down airport security conditions. Fine if you’re happy with that we certainly are.

And just one final thing. The lesson I draw from the history of anti-Semitism and the holocaust is that racism must always be opposed and fought. The Zionists lesson is that only anti-Jewish racism (under which rubric they classify all opposition) needs be opposed. So they have nothing to say about the routine ‘death to the Arabs’ march each year in Israel, a terrible echo of the ‘death to the Jews’ marches that Poland and the Baltic Republics experienced (there were no such manifestations in Nazi Germany where Nazi terror was also directed at Germany’s non-Jewish populace.

My report is at http://azvsas.blogspot.co.uk/2012/05/habimahs-merchant-of-venice-goes-ahead.html

This is one of the most interesting debates that I have read. As someone who is acutely aware of the Israeli/Palestine conflict and have many freinds who fall on both sides of the divide, I was riveted as I read the different posts.

I do feel, however, that there is another point that is not being made concerning the Globe’s policy over this festival. They seem to have chosen only “established” or “prestigious” companies to participate. I personally feel that this represents a lost opportunity. There are, for example, in Israel Jewish artists who actively resist the Israeli State’s position. How much braver would it have been for the Globe to invite one of those companies – a company which is perhaps made up of actors from the Jewish and the Palestinian communities. They exist … they receive a lot of hostility from both sides … but a perfomance by a company like that would be a courageous statement and an opportunity for lesser known artists …

Colin – a fascinating thought, and you’re very right, I think that could have been an interesting stance for the Globe to take.

I appreciate the mostly thoughtful discussion above. Although Tibetans and other groups experiencing oppression deserve our support, I, as an American, feel particularly responsible for doing something to help the Palestinians. That is because my own government has been responsible for subsidizing the settlements, perpetuating Israeli violence with no accountability on how the weapons we supply are used, and getting Israel off the hook any time it violates international law. I presume that many British and Australian protestors feel the same way, especially with regard to the last point.

I’m respectfully puzzled by the following: “its presence on the South Bank both gave a voice to Hebrew-language theatre and, more importantly, legitimised a peaceful protest.” This seems to translate as: an unjustifiable action or performance is fine because it allows people to protest against its unjustifiability. One could easily reduce this argument ad absurdum. However, this is a very thoughtful and in many ways admirable piece – to be able to disagree with certain points and yet commend the whole is refreshing.

Thanks Raymond, that’s a fair pull-up on confusion. Instead of “legitimised” I should really have written “gave occasion to”. The arguments for and against ‘no platform’ policies can be debated elsewhere, but personally I found it useful to have the opportunity to see these debates in a context where I do have expertise (Shakespearean theatre) and think seriously about them.

I well remember when organising a rent strike at university in protest at the university banking with Barclays (when Barclays was a leading bank in apartheid South Africa) being hauled up before the Master and asked why I wasn’t complaining about the treatment of rubber workers of Singapore, or labour conditions in Malawi etc. It may very well be that Israel is not the most oppressive state in the world, and it might even have been true back in 1978 that there were worst places to be living as a black person than South Africa, but this does nothing but deflect consciously from the issues that are being highlighted. Indeed one would have more respect for these arguments if their proponents took their own injunctions seriously and protested about what was going on in north Korea, Syria or wherever. It’s a cynical device to deligitimise protest, and is used to suggest that since Israel might not be the world’s worst state (although the one presiding over the longest illegal occupation in modern history) protesters must be anti-Semitic or otherwise acting in bad faith. For myself as a British Jew and as a great fan of The Globe I’m appalled that the present artistic regime has behaved in such a morally questionable way.

MTC – there is no similarity between non-violent solidarity in the form of boycott and becoming a suicide bomber, no similar calls for boycott from the countries you mention and while I’m not about to defend Britain’s record on Ireland or numerous other places, again there hasn’t been an organised call for boycott.

Janet:

I never said that there was any similarity. I was asking a simple question of whether you always do what people tell you without questioning (and gave an extreme example) or whether you have independent opinions and make your own decisions. I posted a link to a site that calls for a boycott of China because of its occupation of Tibet. There were widespread calls for a boycott of China during the Beijing Olympics because of its suppression of human rights. So did all the politically-correct progressives in Britain automatically fall into line? I’m sure that if an organised campaign starts tomorrow to boycott the Palestinian Authority you will automatically comply.

Simon Sandberg –

I love the “As A Jew” comments! Do you think that it gives you some sort of moral superiority ? Many other Jews disagree with you, but they wouldn’t think of trotting out that argument the support their opinions.

I see that your excuse for singling out Israel is that it’s “the LONGEST illegal occupation …”. Never mind that like most Brits you conveniently ignore the 800 year occupation of Ireland, or that the occupation of Tibet started in 1950 (I assume the you are only protesting the post-1967 Israeli occupation) but you have implied that the length of an occupation determines the level of injustice. Therefore I infer that the occupation of Cyprus by Turkey is not worthy of your indignation merely because in begin in 1974 !

I’m appalled that you, “a great fan of The Globe” and “a British Jew” has not questioned – or even thought of questioning – the morality of the Globe’s invitations to the Chinese and Turkish theatre groups.

Colin Reese:

“There are, for example, in Israel Jewish artists who actively resist the Israeli State’s position”.

A rather strange comment. Israel is a democracy and similar to Britain, people don’t “resist” govt policies, they oppose them in the usual democratic ways. It would be interesting to get a survey from you how British artists “resist” their govt’s actions in Iraq and Afghanistan (while eagerly accepting govt subsidies).

Many of the members of Habima refused to perform in the West Bank, but of course the facts were never important in this protest. Why don’t you think that inviting Habima to London was a way of encouraging them ? Do you support testing the actors from all countries participating in this festival for their political views and allowing only those that you find politically “acceptable” to perform ? Should the Globe have asked the Ashtar actors their opinion on suicide bombers and rocket attacks ? or does your suggestion only apply to Jews ?

Colin:

You raise an interesting point; as an aside, a couple of years ago, B’Tselem invited Israeli theatre directors to visit the Northern West Bank to “see for themselves the heavy damage to human rights inflicted by the continued existence of the Ariel settlement.” They were suggesting that since theatre was being used within the occupation, it should also take a critical look at that occupation itself.

I was wondering about the Freedom Theatre, and the various projects Juliano Mer-Khamis set up whilst he was alive designed to encourage interaction between Israeli and Palestinian children; as well as the initiatives War Child supports for the same purposes. An invitation to one of these initiatives would have been a much braver, more progressive choice for the Globe.

It’s sad – it feels like there was an opportunity wasted somehow here, and that what could have been used as a means to encourage intercultural participation and debate has simply re-enforced the old entrenched and acrimonious positions.

Anyway, I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on other Israeli artists and companies working with both Israelis and Palestinians – you’re right, this kind of cultural participation doesn’t get enough exposure or support.

Sam:

I’m glad that you mentioned the tragic death of Juliano Mer-Khamis. Whether he was killed because he was an Israeli or whether he was killed by Islamists who opposed the concept of his theatre is not known, and according to reports that I have read the P.A. is apparently not very interested in investigating. There is also the case of the Jenin “Strings of Freedom” children’s orchestra, whose director was ordered out of the West Bank because she committed the crime of taking the children to perform for a group of Holocaust survivors !

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/7978544.stm

I agree 100% with your comment that it is imperative to encourage intercultural participation and debate. I only wonder why you have raised the point in connection with Habima and not with Ashtar, considering the intolerance on both sides.

”…the hostility directed at those who believe in something strongly enough that they feel the need to say it out loud.”

A wonderful phrase! I shall probably find myself quoting it (with attribution, of course). I am one of a small but growing number of Canadian Jews who feel so strongly about the Occupation that we feel the need to say it out loud.

I am impressed by the civil and rational tone of this debate. In Canada, the Zionists would probably have jumped in and been anything but civil and rational. Or maybe not; lately they have backed away from arguments, knowing that the ground they stand on is shrinking.

Protesting other (worse) countries? They aren’t “the only democracy in the Middle East,” or anywhere else. Their inhabitants haven’t asked the world to join in a boycott.

One of my colleagues recently reported hearing a fellow Jew (a Zionist) say “Never again except for the gypsies [i.e. Roma].” How disgusting is that?????

Elizabeth:

“Their inhabitants haven’t asked the world to join in a boycott”. This excuse has been posted before. I infer that you will not initiate or participate in any action against injustice until specifically asked. That’s a very interesting attitude. I wonder if other oppressed befores don’t “ask” because they know that nobody will listen. The Tibetans certainly have asked (I posted a link above), but I guess that we all prefer to buy all those cheap Chinese-made consumer goods. So what you really means is “if they ask AND it doesn’t affect us financially”.

Meanwhile, Canadian forces are involved in the never-ending slaughter of civilians in Afghanistan and maybe one day the Afghanis will ask for help against the foreign invaders. Or perhaps the First Nations people who have had all of their land stolen, have had their children taken from them and sexually abused will ask for help to get their rights back, or maybe Quebec students will ask for help to get their democratic rights back (even the NY Times had an editorial condemning the new Canadian laws that curtail legal protest). Should I then atutomatically obey because these people, so heinously treated by Canada, ASKED ?

“One of my colleagues recently reported hearing a fellow Jew (a Zionist) say “Never again except for the gypsies [i.e. Roma].” How disgusting is that?????”

A Christian Canadian once said to me “if the Quebeckers don’t like it in Canada, they can go back to France” ! How disgusting is that ?

@Avraham Reiss

1. There is no Palestine. It ceased to exist on 14th May 1948 when the British left it.

I’m sorry, you’re incorrect there. In 1947, the UN Partition Plan declared a state for Palestine and a state for Israel. To ignore one is to deny the other.

2. Israel owns the Western Bank following the war declared upon it by Jordan, Egypt and Syria in 1967. When you declare ware and lose – you lose land.Germany was so divided for more than 40 years.

Conquest of land is illegal under international law. Read article 49 of the 4th Geneva convention.

3. Anti-Israeli expressions by Europeans, who do not live in the Middle East, are merely modern day expressions of anti-Semitism. Thank G-d, we have a Jewish state that an protect us.

Lol! Do you seriously think Israel is a safe place to live? Wow! The majority of people who protest are not anti semites. They don’t hate Jews. They hate what the state of Israel does and has been doing for 64 years. We actually want to save you from yourselves.

Judaism is a faith which both Christians and Muslims are commanded to respect. Zionism is an ideology which is repugnant, proud and the complete antithesis of Judaism.

There’s a saying. ‘If Zionism is Judaism, then antisemitism is a moral imperative.’

Take from that what you will. What I take from it is that I need to take the trouble to understand the distinction between the two despite the conflation and blurring and respect Judaism whilst protesting the ugly distortion that has blighted this faith.

I hope you take the trouble to read this and start to look into this issue.

“We actually want to save you from yourselves.”

LOL – that’s right, Jews have a lot of experience with the British trying to “save” them. I simply don’t understand how repugnant people like you, who live in a country that is currently engaged in serial murder in Asia, and which has an uninterrupted history of colonialism and imperialism with its associated racism and exploitation, can so easily adopt a lofty moral position and preach morality to Jews.

It seems that according to your standards, Jews daring to defend themselves is more repugnant morally than Britain sending its troops thousands of miles to Iraq and Afghanistan – UNPROVOKED – with the resulting loss of tens of thousands of civilian lives.

And if you tell others to “look into this issue”, I think the issue you should start looking into is how you British Imperialists manipulated the situation in 1948 for your own colonialist gains, including the funding, arming, training and leading a mercenary army send to invade Israel.

@MTC:

Ha! You’ve kind of made my point. You don’t know what my nationality is, not that it’s important, but I do have some Jewish in my bloodline. No person can singularly control what policies their government holds, but they can disagree with them.

Yes, you’re right. Britain are ‘the bad guys’ as are the US and Israel. That doesn’t make a citizen of any of those nations repugnant which is the tactic you’ve tried to employ here in a completely baseless personal attack.

Israel are engaged in an occupation that is illegal (I notice you didn’t respond to any of my comments pertaining to this as you can’t). The difference is whether you support it or not.

As far as Israel’s existential threats are concerned, I see them largely self perpetuating. Israel has to consider making a hard peace, or consider losing it’s artificial Jewish demographic. Refugees aside, you have a situation where 50% of the population within the borders controlled by Israel are non Jewish. Those people are not going away. The world is starting to see this as Israeli propaganda can’t control the waves of information via the internet. They have to do something soon. See my point?

Steve :

I saw your point right from the beginning. Do you think that Imperialism and Colonialism blighted the Christian faith ?

“A completely baseless personal attack”. This thread is about the Merchant of Venice and the related protests by a group that obsessively denigrate an entire nation and its people, in case you haven’t noticed, a group that has assigned to itself a high level of moral superiority.

I have not expressed any opinions whatsoever here on Israeli policies and I don’t see what connection they have to the issues that I have been discussing. What has happened here is that people like you and Elisabeth can’t even remember that the politically-correct are supposed to denigrate “Zionists” and not “Jews” which doesn’t help your ant-Zionist/anti-semite argument very much. See my point ?

@MTC: Do I think Christianity has been blighted by Imperialism and Colonialism? Yes, it has. Many nations see the cross as a bad thing. That is what happens when you attempt to mix church and State. But not only has the Zionist state of Israel done this, it claims to speak for worldwide Judaism.

To use your words: ‘I simply don’t understand how repugnant people like you’. You called me repugnant. That is a personal attack. My use of the word attacked the ideology of Zionism and it’s outworking of oppression and human rights abuses. As far as having a ‘high level of moral superiority’, maybe so, but even if I were the worst bigot on earth, that doesn’t detract from Israel’s behaviour, which is what you are trying to do here. It doesn’t matter what you call me or accuse me of, Israel are desperately in the wrong both morally and legally.

As far as Elisabaeth’s comments go, I haven’t read them and I don’t know here so I can’t speak for her. As for myself, I can say that I understand the distinction between Zionism and Judaism and I hope others do too, however it appears you’re the one who’s conflating.

As I said in my previous post, Israel needs to make a tough peace. The only reason Israel is attacked is because of what it is doing. The foundations on which it stands are built on oppression, dispossession, violence lies and hatred. Without being propped up both financially and by UN policy from the US, it would have crumbled long ago.

A good analogy: Israel is like a kid with it’s hand in a sweetie jar. Inside are Democracy (for it’s entire population, including those in the territories), religion and territory. It can only take two of the ‘sweeties’ out without getting it’s hand stuck.

It can be a Jewish democracy. Give up the territories.

It can be a Secular State. Walk away from Zionism.

It can be a ethnocracy that gives privilege to some and not others. This is basically what it is today whilst pretending to be ‘the only democracy in the Middle East’.

Personally I want to see Israel straighten itself out. The arguments for a safe haven for Jews is entirely baseless. If I were a Jew, the last place on earth I’d want to live is there. Can’t you see that this is all of Zionism’s making? It’s all unraveling. Israel exists completely on the policies and financing of it’s war machine by the US and that support is crumbling. What’s next? Will Israel start to foster relationships with states like China or North Korea?

All I can say is you keep supporting it and I’ll keep protesting it. The protesters aren’t going away, neither are the Palestinians. Hopefully I’ll be on the right side of history, because supporting the current situation will only lead Israel to Masada.

I hope that clarifies my position, but if it’s unclear, I’ll put it in one sentence. I support Israel’s right to exist within peaceful borders offering full and equal rights to all those within them.

Whether it’s one state or two states is really down to Israel, but they can’t have it all.

In view of all the fuss, I decided to see the play (and the protesters) for myself. It was all very confusing. Outside, pro-Palestinian protesters waved placards condemning Israeli “apartheid”. Inside, Bassanio (played by an Israeli Arab) wooed and won Portia (played by an Israeli Jew). This is not apartheid as I remember it.

Although I’m quite old, I have a pretty clear memory of what apartheid was, and why I opposed it.

Under apartheid, a racially mixed national theatre company, such as Habima, would have been unthinkable.

Under apartheid, only white South Africans were allowed to represent their county in sport (Israeli national sports teams are integrated with Arab players promintent, for example, in the national football team).

Under apartheid, only white South Africans were allowed to vote in national elections (in Israel it’s one person, one vote – with Israel’s Arab minority better represented than any minority group in the UK Parliament).

Under apartheid, all positions of power and authority were reserved for whites. Whites dispensed”justice” to non-whites. In Israel, an Arab Judge sent the Jewish (former) National President to prison for rape. Not a good thing for a country to have a rapist as President; but very good that justice is blind and no person (Jew or Arab) is above the law.

Of course, Israel is not a perfect society. No country is. But it is not an apartheid state and it is certainly a more enlightened, tolerant and free society than many countries whose representatives have been able to perform Shakesepare at the Globe free from insult and harassment. Maybe the Israelis should feel honored that they are being held to a higher standard than all the other countries. But to my mind, this double standard reeks of racism.

@Ian,

The protests are not about Israel’s domestic policies. I think you’re correct in much of what you say, but you are being rather specious about Israel’s geography and demographic, although I don’t know whether that is intentional or not. The protests are about the occupation of the West Bank and air, sea and border control over Gaza.

When you take into account that Israel’s entire controlled area comprises of a population of around 4 million people who don’t have the right to vote and are not considered as Israeli citizens, you have an entirely different picture. Israel won’t grant them citizenship as it will destroy their demographic of having a Jewish majority, but at the same time, they don’t want to surrender the occupied territories, and rather continue to build settlements and transfer their civilian populations there, both of which are illegal under international law.

In addition to this, Israel controls the water supply to the settlements by diverting water from Palestinian villages and food entering Gaza. Despite the millions of tons of aid that Israel allow to pass through, people are being sustained on minimum dietary requirements. Effectively, they’re being starved into submission, rationed on electricity and medical supplies and forced to pay inflated prices for bottled water.

Desmond Tutu describes the situation as apartheid. Nelson Mandela describes the situation as apartheid. Even Israel describes the situation as apartheid. The apartheid wall is known in Hebrew as the Hafrada wall. Hafrada means separation. Apartheid means separation. It appears no one has an issue with the description, the issue lies with the comparison and connotations of South Africa in the 1980’s.

I’m sure many here will pass the blame onto the fact that Palestinians are terrorists. I ask you to consider this. There are 4 million people living in the territories. They are not all terrorists. Estimates are around 3,000 active terrorists, which Israel are at liberty to detain without charge and in many instances execute without trial in what they eloquently call ‘targeted killings’. To suggest that Israel needs to keep these ‘terrorists’ at bay is like saying the entire population of London should be cordoned off and banned from leaving the area because of the riots last year. It’s collective punishment.

But it’s not about collective punishment. It’s about taking land. Israel believes it has a divine right to the West Bank and Gaza and the Palestinians are a stumbling block to their ideology.

@Ian

I’m pleased to pick up on comments that are related to the play and event that this blog was immediately about. I find your note about Bassanio and Portia interesting; and those interested in Habima might like to know that this actor, Yousef Sweid, was one of the Habima actors who refused to tour the settlements. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/israeli-actors-refuse-to-take-the-stage-in-settlement-theatre-2065489.html .

On your note about an Israeli Arab wooing and winning an Israeli Jew, was it that simple? My abiding memory of the performance was a triumphant Bassanio far more interested in the contract he had won from his successful guess, and his embraces with his companions. Portia, on the other hand, stood waiting and increasingly upset for some time before he finally ‘claimed her with a kiss’. Considering the problematic depictions of race within this production epitomised by the ‘blacked-up’ Morocco, and the deeply ambivalent nature of the ending as the Venetian men were left at least partially abandoned by their women, I think it’s difficult to claim that this production displayed or advocated harmony.

Peter, you have totally missed my point about the casting of Bassanio and Portia. You have confused the actors with the parts they play. Of course, the production doesn’t display harmony – how could it? It’s a production of The Merchant of Venice. You’d have to turn the text on its head to find a display of racial harmony within it. The play depicts racial intolerance and it would be stupid to pretend otherwise. This production, like every good production of the play, shows us that intolerance. As to the blacking up, here’s what Shakespeare has Portia say about Morocco:

“A gentle riddance. Draw the curtains, go.

Let all of his complexion choose me so. “

So Habima got it spot on here.

But my point was about casting. Habima picked the best actors available for the roles, regardless of their race. So we find an Arab actor portaying an Italian anti-semite wooing a Jewish actress portraying an Italian racist. Nothing remarkable about this – except that it disproves the aparthed libel.

By the way, thanks for pointing out that Yousef Sweid was one of the Habima actors who refused to tour the settlements. This obviously didn’t prevent him from being cast in a leading role in this production. What a pity he had to endure the taunts of the bigots who tried to disrupt his performance at the Globe – it would seem that “sufferance is the badge” of all Israelis – not just the Jewish ones.

@Steve

Hard to know how where to start unpicking all the misinformation in your post. For now, I would just note that you failed to answer my main objection to this discriminatory boycott. It’s just plain wrong to single out the Israelis for abuse at a festival in which actors representing countries with far worse records (such as China) are allowed to perform un-molested. This racist double standard is simply indefensible.

@Ian – I didn’t miss your point, I’m just complicating it, as the interplay of casting and the play itself is very interesting to me. The use of blackface in particular is something very rarely seen on the UK stage; while the character may be the same, there’s a big difference in the semiotics of the role as played by a black actor versus played by someone covering themselves in black paint, and I didn’t think the company went nearly far enough in problematising their own practice here, especially in the context of the colour-blind casting elsewhere. I’m not disagreeing with you, but in the context of the rest of your comment, I felt it was useful that we acknowledge the problems with race both within the play itself and in the company’s playing choices.

In response to your comment about this production being singled out, that’s already been discussed at some length in the comments threads on both blogs. The ‘singling out’, according to protesters, is based not on the fact that this is an Israeli company (see Colin’s very interesting point earlier about other Israeli companies who might have been invited) but about the invitation to Habima specifically on account of the company’s choice to perform in disputed areas. Whether or not you believe the protesters is up to you – @MTC has already called this a convenient excuse. But as far as I’m aware, none of the other COMPANIES involved in Globe to Globe have been accused of complicity in their government’s actions; and I think it is important to note that that is the distinction being drawn.

I would be genuinely intrigued to know if the companies Sam mentions would have been greeted with the same response.

@Peter

If by “complciating” you mean “muddling and obfuscating”, then you succeeded. Till now, I have let you get away with the assertion that Morocco was portrayed in blackface – though this conjours up the picture of Olivier in full black and white minstrel greasepaint in his film of Othello. In fact, as you will recall, the actor had just enough articificial suntan applied for Portia’s remark about his complexion to make sense. Are you saying that Habima should have sent out for a Moroccan to play the part? I’m pretty sure that the other companies in this festival are allowed to field their indigenous cast members, even if that means Chinese or South Asian performers portaying European characters. But double standards do seem to be the order of the day.

The claim that Habima (including the cast member who refused to perform in a settlement) was singled out for abuse because it performed in a settlement and not because it is Israeli stands exposed as a transparent figleaf. Israeli companies are targeted by the boycott bigots regardless of whether they perform in settlements Last year the Israel Philharmonic, this year Habima. If you’re Israeli, expect abuse.

And the fact remains that Israel’s record on human rights is better (not worse) than many of the other countries whose actors are allowed to perform without abuse.

Peter:

It’s sad that we won’t get to find out. For what it’s worth, Juliano Mer-Khamis’ film ‘Arna’s Children’ was well enough received to win best documentary at the Tribeca festival in 2004, and there have been well-received events in London celebrating the work of the Freedom Theatre up to now. As another aside, they received emphatic support from Judith Butler after a visit this April just gone.

It’s an odd one, isn’t it. There are a range of British theatre companies that I wouldn’t want speaking for me at an international festival; same goes for a whole load of British figures, bodies, companies and institutions in the public eye. And I would hazard a guess that a significant amount of Israelis – Haaretz’ readership? – wouldn’t be enormously comfortable being represented internationally by a company who had first toured the occupation.

@Ian

Why do you need to apply anything to the skin in order to “make sense”? You’re entirely missing my point. In a colour-blind production (where actors are cast based on suitability of the role, regardless of physical appearance), there is no need for any form of ‘blacking up.’ What I would have expected would have been the actor to simply play the role in costume and let the language do the imaginative work; or use grease paint but build in a much more severe critique of Portia’s racism (as recent RSC productions have done) – rather than skate past it, as was done here. There’s not a double-standard – it’s just as much of an issue if, to use your example, a Chinese actor was to “white up” in order to play a European – it falls into dangerous racialising, stereotyping patterns, which UK theatre has largely abandoned, and the alteration of an actor’s skin tone for the sake of a specific role is an important element to critique in relation to the company’s casting decisions.

The fact that other Israeli companies have been targeted in other contexts doesn’t alter the fact that the protest here is specifically, explicitly aimed at this company’s practices; even if other companies have been targeted unfairly, that doesn’t mean ergo that the targeting of this company is also unfair, that doesn’t logically follow. As an honest and interested question, can you (or anyone) defend Habima’s decision to perform to audiences which exclude Palestinians in the settlements? I don’t think I’ve seen anyone try to do that yet, as people have quickly moved to the broader political issues, and I’d be interested to hear views on the specific debates about this company.

@ Ian:

Apologies, I didn’t answer your question. I’ll try now. You’re right. I think all nations should be held to exactly the same moral standards. I stumbled on this blog via a link and found a post from Avraham with complete disinformation, posted a refutation and found myself defending my comments. I have a particular issue with the Israel / Palestine conflict for personal reasons, I’ll admit, but that doesn’t mean other human rights issues don’t deserve an ear.

In regard to you unpicking the misinformation I supplied. Please feel free to question me. I’ll happily provide sources.

Regards

Steve

Thought this was a sensitive account of an ugly evening. It chimed with the feelings and thoughts brought back by a friend of mine.

Steve:

“The apartheid wall is known in Hebrew as the Hafrada wall. Hafrada means separation. Apartheid means separation. …. To suggest that Israel needs to keep these ‘terrorists’ at bay is like saying the entire population of London should be cordoned off and banned from leaving the area because of the riots last year. It’s collective punishment.”

So how would you describe the Belfast Apartheid … ooops – Peace Walls. Every time I ask a Brit this question I get the same answer – “good walls make good neighbours”. Except that the “ggod” was at the end of British army rifles. So what’s the difference, other than typical British politically-correct semantics. Those walls were also designed to keep people apart. AND … the walls have actually expanded since the signing of the Good Friday agreements. Have you ever seen pictures of the Belfast Wall ? Some parts of it dwarf

the Israeli wall !!

So what’s the difference ? simple – Desmond Tutu, Nelson Mandela, Ronnie Kasrils and a cast of thousands simply don’t care of the brutal, racist, murderous and bigoted 800 year occupation of Ireland, the same way they don’t care about Tibet, Cyprus or any other injustice in the world.

Here is a news release that I found:

“Figures provided by the MOD to Parliament show over £400,000 was spent taking professional singers, dancers, musicians and comedians to Afghanistan in 2011.”

These artists are obviously “supporting” the unprovoked British occupation of Afghanistan. Will their performances be interrupted in the future by those who oppose the British role in Afghanistan, an invasion that has taken the lives of untold numbers of civilians.

(BTW, according to the Guardian the British army does not even bother to count the number of civilians that they kill, so it is impossible to get accurate figures). Well, I guess that a soldier needs a good laugh at the end of a hard day …..

@MTC – In the interests of transparency, do you have a link to that news release?

Your note on the “Belfast Apartheid” is interestingly timed, as it’s now the first of June 2012, and this month the IFI’s “Peace Wall Programme” is due to be starting work liaising with communities to begin the process of dismantling the walls; would you consider this a positive step?

http://www.internationalfundforireland.com/media-centre/449-international-fund-for-ireland-announces-p2m-peace-walls-programme

Peter:

Sorry – I always post the links. Here it is:

http://bfbs.com/news/afghanistan/mod-defends-afghan-entertainment-costs-54350.html

Re Belfast – of course dismantling the wall will be a positive step – as will dismantling the Israeli wall ! Dismantling physical walls is very easy; it is the mental walls that are difficult to deal with.

Just to clarify things, my argument here is not about Israeli policies, and as you can see I have avoiding expressing my opinion on them. The issue here is the nature of the protest and the hypocrisy of the people protesting. Protest by all means – but protest against everyone, particularly yourselves. Some of the replies above are particularly pathetic – ’ I don’t protest against China because nobody told me to protest’. Are we supposed to take that seriously ?

and here is the link to the unknown Afghanistan body count:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2010/jul/04/afghanistan-body-count-civilian-deaths

@MTC:

You skills at deflection are very poor. Pointing fingers elsewhere? Come on! Two wrongs or even ten wrongs never make a right.

You suggest I support the British involvement in Ireland. I don’t. I haven’t studied it much although it is on my list, but since studying the Israel Palestine conflict, I have dramatically shifted my position from that of a right wing patriot to the left. I think Britain and the US are very much the bad guys along with Israel. Ireland was wrong, Iraq was wrong, Afghanistan was wrong and we’re staring down the barrel or war with Iran, which is something that Israel, in it’s delusional paranoid condition is the biggest sabre rattler. Israel is very much the ‘hot topic’ at the moment due to media coverage and Palestinian PR work, but they’ve had to become good at this to wash away the Israeli propaganda machine (Hasbara) that has been in place since Israel’s inception. People don’t like to learn they’ve been lied to and Israel has been doing since day one to justify itself. If you lie to enough people and they realise it, you suddenly find yourself with a hell of a lot of enemies. It’s called ‘blowback’.

As far as the wall is concerned what we’re dealing with here is a purposeful campaign to make life as difficult as possible for the indigenous people of Palestine, rather than keeping terrorists out. You do realise that the wall is breached by over 1,200 Palestinians every week to work illegally in Israel? Suicide bombers are messed up people and I’d applaud Israel if they took meaningful measures against them, but to say that the wall keeps terrorists out suggests the terrorists are completely stupid. If they want to set bombs off in Israel, they will, but the truth is, Palestinians finally understand that violent resistance doesn’t work against Israel’s might and for the most part they have chosen a path of non violent protest and they’re winning this war hands down. Why? Because they have right on their side and the truth ‘will out’.

Walls and checkpoints are only serving to detain and mess with the lives of ordinary people. To think that the wall is about security is simply false. It’s about appropriating land (10KM past the Green Line?) and making life hard for people so they’ll emigrate.

I suggest you check out the following book.

http://www.amazon.co.uk/The-Generals-Son-Journey-Palestine/dp/193598215X

Miko Peled comes from a very distinguished Zionist family. His grandfather was a signatory of Israel’s Declaration of Independence and his father was a General in the Israeli military who pushed for Israel’s preemptive attack on Egypt, starting the 19967 war. He’s a peace activist along with his sister. He’s suffered loss by Palestinian terrorists but continues to campaign for full and equal rights for Jews and Arabs in Israel and Palestine.

This isn’t about hating Israel or siding with Palestinians. It’s about peace and justice. At the moment, Israel is causing the problem. Am I being unreasonable to suggest that Israel should offer equality to all those within it’s controlled borders?

Steve:

Your skills at deflecting are even better. Unfortunately you don’t even realise that you are doing it. I clearly stated that I am not discussing the I/P conflict and who is “right”. Why ? Because this article is about the Habima production of the Merchant of Venice and the ensuing protests. So by confining my arguments to the issue I am hardly “deflecting” from the topic.

I’m glad you have a list, I’m glad that you’ve seen the light, I’m glad that you have read a book – I hope that you have understood, even though you don’t seem to understand the few paragraphs that I have written.

@MTC:

Personal attacks? Really classy.

I’m glad you’re happy for me. I did however read and understand what you had to say, which was nothing about why people protested (I suspect that’s because you know that your arguments won’t stand up to the slightest scrutiny) and quite a lot about how you feel people should protest about something else. Very typical Hasbara tactic. Yawn.

People protest about things because the cause resonates with them. Just as apartheid South Africa did some 20 odd years ago and the civil rights movement did 40 odd years ago. If anyone is the hypocrite as you say, it’s not those standing up for something. Why don’t you join us. We can put this one to bed and move onto Northern Ireland or Tibet, or should we all shut up?

I’m really sorry that Palestinian solidarity is getting bigger and bigger and will soon force Israel’s hand to make the changes they need to make, but there really isn’t anything you can do about it. Whining like some luvvie about how uncouth it all is just ain’t gonna wash. Protest isn’t designed to be pleasant or nice and fluffy. It’s about putting your head above the parapet. So far you’re just shooting blanks dahling. 😉 You’ll need to do better to shoot through my hide.