March 4, 2012, by Peter Kirwan

King Lear (Shakespeare at the Tobacco Factory) @ The Tobacco Factory, Bristol

Writing about web page http://sattf.org.uk/currentfutureproductions/kinglear2012.html

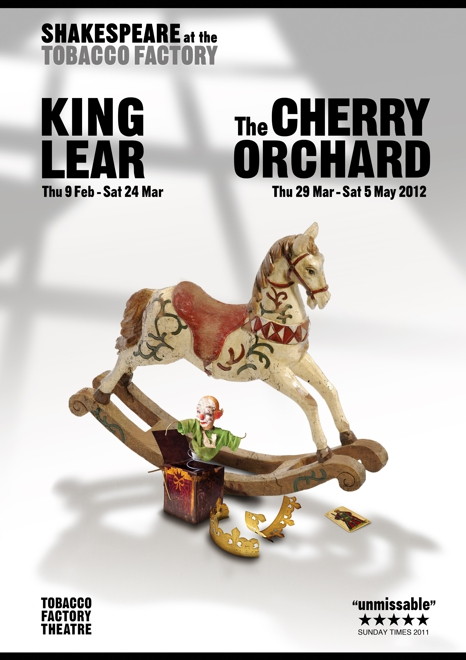

With only one Shakespeare play in this year’s Tobacco Factory season (the company are putting on The Cherry Orchard in place of a second), SATTF director Andrew Hilton has chosen to go back to the play that launched the company twelve years ago. Continuing the work of last year’s similarly pared-back Donmar production, King Lear appeared once more as one of the starkest of Shakespeare’s tragedies: a raw, bare exposure of flawed humans.

Despite the use of a conflated text and a 3 hour 10 minute running time, the striking feature of this Lear was its pace. Arguments escalated into violence in a matter of seconds; soldiers and messengers appeared and disappeared; John Shrapnel’s Lear stomped about the stage with a brisk bark as if continually running out of time. This was a play of action rather than reflection, with events racing towards the ‘promised end’.

Shrapnel’s Lear, though diminutive in stature, was nonetheless a commanding presence. His naturally avuncular air, foregrounded in an opening entrance filled with laughter, gave way quickly to surprise and sudden rage at Eleanor Yates’s Cordelia’s pleading resistance. The attempt to provide psychological complexity to this sequence rather muted the effect, however – Shrapnel’s clear willingness to hear the positive in her words rendered the transition between love and banishment too superficial, responding to the words as spoken rather than to an organic sense of resentment.

A similar complaint might be made about Lear’s relationships with all three of the daughters. On the one hand, the production was keen to find sympathy for Lear, with the two elder daughters taking hands against him and a blustering Cornwall (Byron Mondahl) stacking the odds against an increasingly isolated king. On the other hand, Shrapnel delivered his insults, particularly to Julia Hills’s Goneril, with a malice that went far beyond the rational, and both Hills and Dorothea Myer-Bennett as Regan brought a righteous indignation to their earlier complaints. While complexity is no bad thing, the competing sympathies muted rather than heightened the sense of conflict. It was only in the second act, when Regan and Goneril began raising eyebrows and smirking at each other as their relationship disintegrated, that the play began revelling in the deliciously intractable and inexcusable crimes of its characters.

The dramatic interest in the first half came instead from Jack Whitam’s dynamic Edmund, amusing in his incredulous assertions of his kindred’s gullibility and engaging as he ran around all four sides of the Tobacco Factory’s audience, waiting for answers to his rhetorical questions. The imposition of what seemed like a very early interval (Lear leaving Gloucester’s house, as opposed to after the joint-stool scene or even after Gloucester’s blinding as in other recent productions) meant that Christopher Staines’s Edgar had less opportunity to make a mark before the interval. Once in disguise, however, he was an ideal opponent of Edmund. Wearing only a loincloth, and with twigs sticking out of bloodied gashes in his arms, his poor Tom was a wiry and wired presence, speaking quickly and providing an unwitting catalyst for Lear’s own destabilisation.

Comic relief was provided by Simon Armstrong, who gave a wonderfully brusque performance as the disguised Kent, and by Paul Brendan as his nemesis, Oswald. Armstrong’s stomping, plain-speaking performance deliberately mirrored Lear’s, positioning the character as one to whom Lear begins to aspire in his decline. Brendan’s Oswald, meanwhile, was a swaggering coward, who ran about the stage shrieking when challenged by Kent before turning to flourish his sword grandly at him once Cornwall and Regan had arrived. Christopher Bianchi’s Fool was less funny but perhaps more significant than other Fools I’ve seen. In ruff and long jerkin, he delivered many of his lines quietly and calmly, interspersed with the occasional song and skip. The clarity of his words was, however, key; and the scene in which he sat with Lear and Lear whispered “Let me be not mad” was perhaps the production’s most moving sequence, the friendship of the Fool allowing Lear to finally admit what he had hitherto only feared.

The play’s second half began with thunder and lightning as Kent and the Gentleman shouted to one another, followed by Lear speaking to rather than attempting to shout down the storm while the Fool shivered beside him. It was at this point that the action of the play began to noticeably accelerate, rushing through the chaotic encounter with Tom and the joint-stool scene, which saw Kent bury his head in his hands as the insanity built around him.

Yet it was tenderness that informed subsequent scenes of insanity. The Dover cliffs sequence was played out slowly and sensitively, and Lear’s encounter with the blinded Gloucester (Trevor Cooper) was tender, culminating in the two men sat cradling each other’s heads and Gloucester moaning as Lear finally acknowledged him. As usual for this play, the breakdown of Glocuester’s spirit was one of the more moving aspects, following on from a brutally brief eye-gouging sequence that was slightly unbelievable in its efficiency, but gave Cooper a chance to spit defiance at Cornwall and Regan, by this time fully embracing the nastiness of the characters as they sneered at the trapped man.

As the play drew to its close, Goneril and Regan were foregrounded as the backstabbing began, with some lovely touches as, for example, they took hands before Albany as they left the stage, but then wrenched them apart as soon as they were out of his sight. Alan Coveney grew to prominence as a dignified Albany, and as he finally issued his challenge to Edmund, Goneril’s fear as she shouted “An interlude!” spoke to a newfound respect for her husband. The two daughters handled their decline fantastically; Myer-Bennett’s cool resolve slowly collapsed as she fell ill, while Hills effectively ran mad, realising after Edmund’s defeat that no-one was listening to her any longer. The most powerful image from this plot, however, remained Edmund’s satisfied smile as he announced “But Edmund was beloved”.

With the bodies of Goneril and Regan kept offstage, all focus was on Lear and Cordelia’s body, the king appearing immediately as messengers ran off the other way. Fittingly, for such a sparse and bleak production, Shrapnel simply bowed his head over his daughter and never rose, and the play ended on the image of Kent kneeling beside the two bodies while Edgar rose and addressed Albany. If not an inventive Lear, the sparseness and emotive power of the performances made it a fine and faithful one, prioritising a story of broken relations and an unforgiving world.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply