May 11, 2016, by Editor

Philippines 2016: How ‘Dutertismo’ can make a difference

Written by Roland G. Simbulan.

The clear mandate given by the Filipino electorate for Davao City mayor Rodrigo Duterte as the next president of the Philippines in the 2016 elections is a clear signal that the nation urgently seeks meaningful social change. The Commission on Elections estimates that 84% of voters participated in the 2016 elections, making it the largest turnout in Philippine electoral history. It was an election that gave a landslide victory to a provincial mayor from Davao, a city that was once the bloody battleground between New People’s Army guerrillas and government security forces. The military and police forces then also organized the Alsa Masa, a dreaded paramilitary group that assassinated even sympathizers of the armed and unarmed Left. It is to the credit of Duterte that Davao is now considered one of the safest places in the country to live in. The mayor from Davao is also known to be on speaking terms with the outlawed New People’s Army (NPA) who have occasionally turned over policemen and soldiers to him who had been captured as prisoners of war (POW). He is also known to be a supporter of indigenous peoples’ rights, Moro people’s rights, in general for the poor and underserved in Mindanao, though in a controversial speech during the campaign he threatened labour unions with annihilation should they disturb industrial peace under his administration.

Despite his lack of national political machinery and his last minute decision to enter the presidential contest, the irreverent and ‘provinciano’ Duterte was elected the first president from the island of Mindanao, considered to be the last frontier and backwater of the Philippines. Like a loose cannon, he badmouthed even Pope Francis, publicly bragged about his womanizing, and hurled insults at foreign ambassadors, many expected these campaign booboos would lead to his sure defeat. But his ‘Dirty-Harry’ reputation widely documented by national and international human rights human rights groups, of summarily executing criminals in the city where he has served for 20 years also did not discourage nor scare the voters.

His supporters in fact point to his leadership in Davao City as evidence that Duterte gets things done in curbing not only criminality, but also in effectively enforcing the country’s laws like the ban on smoking in public places, enforcing traffic rules, reducing crime and illegal drugs significantly. He has made the city’s police force and local government units as one of the most disciplined civil servants in the country. This effectiveness as a local official had caught the attention of the nation that has long sought an effective leader who can make things happen and who is able to enforce effectively the country’s laws, notwithstanding Duterte’s irreverent and cursing language. For better or for worse, this reputation has evidently caught the imagination of the national electorate who consider him a Lee Kuan Yew on the rise, cutting widespread support through all social classes especially the middle class, public utility drivers, farmers, urban poor and indigenous peoples. His staunch critics however, have profiled him as a resurgence of the dictator Marcos, Hitler, or Pol Pot, among others.

But Duterte is not just known as a leader who talks and acts in an unorthodox manner ‘outside the box’. During the campaign for the presidency, Duterte has described himself as a ‘socialist’ and he has said that, if he is elected, he will be the first Left president of the Philippines. He has declared his admiration for his former professor during his college years, the founding chairman of the Communist Party of the Philippines Jose Ma. Sison, and whom Duterte has invited to return from exile in Europe. These remarks have created ripples among disturbed sections of the Philippine military that has fought protracted battles against the longest-running armed insurgency in the country. They have also disturbed the Makati Business Club who had invited Duterte during the campaign period to present and assure them of his neoliberal economic agenda. They were disappointed when he used the occasion to hammer on his tough crusade for peace and order and on giving more support for basic services. Duterte has also attacked the country’s oligarchs who have for more than a century, monopolized economic and political power. Known to be a wide-reader, has he perhaps also been inspired by the late Hugo Chavez of Venezuela in swagger and substance? A journalist friend who had visited the mayor’s house in Davao swears that she saw a biography of the late Venezuelan socialist on his bookshelf.

Recent academic studies by the Center for People Empowerment and Governance (CenPeg) show that the country’s national and political system is controlled by roughly 178 political dynastic clans. 80% of the Philippine Congressional seats are controlled by political dynasties. From the post EDSA 1 period, 1987 to 2010, single political families dominate gubernatorial and congressional positions in 23 of the country’s 80 provinces. Economic growth rates – the highest in Asia – have only been cornered by the few: the forty riches families control 75% of the country’s wealth; meanwhile the country’s poor in both rural and urban areas wallow in increasingly extreme poverty. That is why, to those who claim that Duterte’s rise and presidency will be a threat to democracy, my answer is, what democracy, we were never a democracy, for what we have in fact is a well-entrenched oligarchy. Is it irreverent too to say that it is only a democracy for the elite?

This unorthodoxy in both his views and actions serves as the potential of Dutertismo. The grassroots movement of volunteers that became his campaign machinery that won him the elections, demolished the vaunted money-based political machineries of the traditional political parties of the oligarchy. As I have noted in social media and during interviews on television and radio, Duterte and the grassroots movement have the potential of being game-changers in a political and economic system that has long been tightly controlled by the oligarchy and its foreign partners.

Dutertismo, if it aligns and taps the experience of the resilient progressive people’s movement of the Left, can go a long way to promote an alternative program that is consistently advancing national sovereignty, for national industrialization, genuine agrarian reform and for an economy truly controlled by Filipinos. After all, it was Duterte himself who stated during the campaign that, he is willing to copy an economic and political program if it is for the good of the poor majority and of the nation. It is the Philippine Left – the legal and armed Left – that has always consistently advanced an economic and political program that is pro-poor and advances national sovereignty.

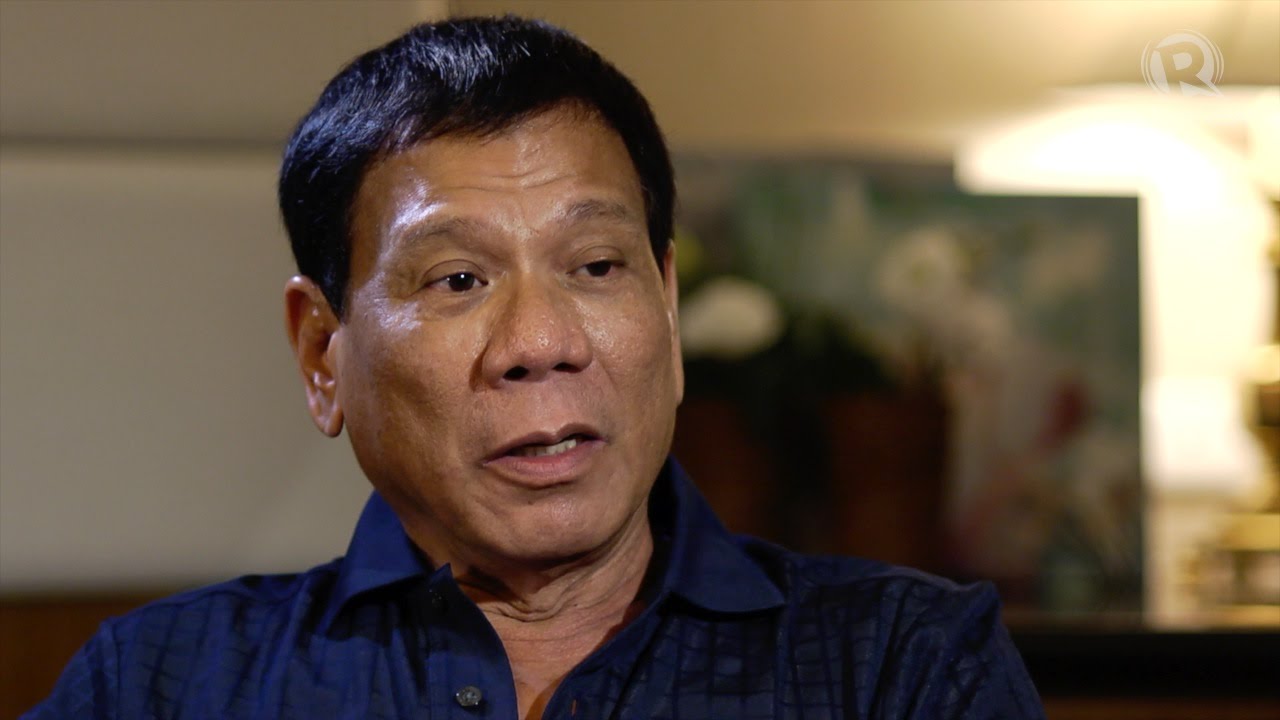

Roland G. Simbulan is a Professor in Development Studies and Public Management at the University of the Philippines. Image credit: Screencap/Youtube.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply