April 13, 2016, by Editor

In the footsteps of Freda Bedi

Written by Andrew Whitehead.

Over Easter, with the support of a small grant from the IAPS, I was in India on the trail of Freda Bedi. You may not have heard of her – but her life was remarkable for the way in which she challenged and crossed boundaries of race, religion and nationality.

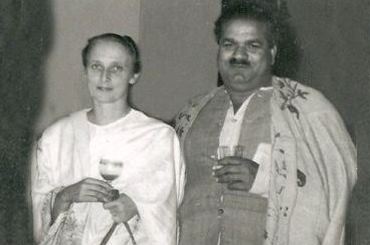

Freda Houlston was born in Derby, where he father had a small watchmaker and jeweller’s shop. She won a place at Oxford University, where Barbara Betts (better known by her married name, Barbara Castle) was a particularly close friend. She got involved in left-wing politics and went to meetings of the Majlis, the Indian students’ society. In the summer of 1933, Freda married her Punjabi fellow student, B.P.L. Bedi, at Oxford Registry Office (the accompanying photo of the couple was probably taken for their engagement) – the first Oxford woman undergraduate, she believed, to marry an Indian student. The college disapproved of the romance and disciplined her for not observing chaperone rules; her family took a while to come round; her friends were supportive throughout. ‘Thank goodness’, Barbara Betts declared on being told by Freda of the impending wedding. ‘Now at least you won’t become a suburban housewife.’

From the moment of her marriage, Freda regarded herself as Indian and dressed in the Indian style. By the time, a year later, she and B.P.L. along with their baby son arrived in Lahore, the husband-and-wife team had published a book in German about Gandhi and edited three volumes for Victor Gollancz about the economic, fiscal and constitutional problems besetting India. In Punjab, both became active in left-wing and nationalist movements; during the Second World War, both spent time in jail; after independence, both moved to Srinagar and worked closely with Sheikh Abdullah to support his goal of creating a ‘New Kashmir’.

In the 1950s, Freda’s lifelong spiritual quest found a home in Buddhism. When she went to work with the Tibetan refugees streaming across the Himalayas after China’s suppression of their uprising, she realised the importance of keeping together the community of incarnate lamas and their teachers. She set up a Young Lamas’ Home School in India – became herself ordained as a Tibetan Buddhist nun – and accompanied some of this new generation of Tibetan spiritual leaders on landmark journeys to California, Canada and elsewhere. Her husband also turned to a spiritual life – in his case, a form of mysticism and healing which borrowed from both Sikh and Sufi traditions.

On my Easter research trip, I spent valuable time in Mumbai with Freda and BPL’s second son, Kabir (yes, that Kabir Bedi – a big film star). In Bangalore, Ranga, the oldest of their three children, shared with me his astonishing family archive of letters, photos, documents and recordings. Accompanying this post is my photo of Ranga in his study sorting through some of the archive – behind him is a painting by his wife, Umi, depicting Kabir as a novice Buddhist monk in Burma. In Delhi, I met Manorma, another member of the extended family who shared memories of living with Freda and B.P.L. at that crucial moment when both became increasingly absorbed in spiritual interests.

One of the most intriguing letters I was given access to was written to Freda from jail by the Kashmiri nationalist leader, Sheikh Abdullah. It dates from October 1946, and he warned that Kashmiris would need to ‘prepare themselves for a final onslaught on the citadel’ to rid themselves of princely rule and establish representative government. In little more than year, Sheikh Abdullah assumed power in Kashmir in one of the more remarkable, and least studied, aspects of the end of the British Raj.

Among the other items, there’s a wonderful collection of letters that Freda wrote over more than forty years to a college friend who, at the end of her life, gave them back to the Bedi family. And then there are the audio recordings – Freda’s own story of her life set down for her family, and now of immense interest to her biographer.

It will take weeks to digest all the documents, photographs and tapes which – with the family’s blessing – I have copied and brought back to the UK. And I also have interviews with family members to transcribe and lots ofnew leads to pursue. The more I find out about Freda Bedi, the more absorbed I become in her personal, political and spiritual journeys. Watch this space!

Dr Andrew Whitehead, an honorary professor at the University of Nottingham, is writing a biography of Freda Bedi. Image credit: Wikipedia Commons.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply