March 7, 2016, by Editor

The EDSA revolution at 30: what does it mean for the poor in Philippines 2016?

Written by Pauline Eadie.

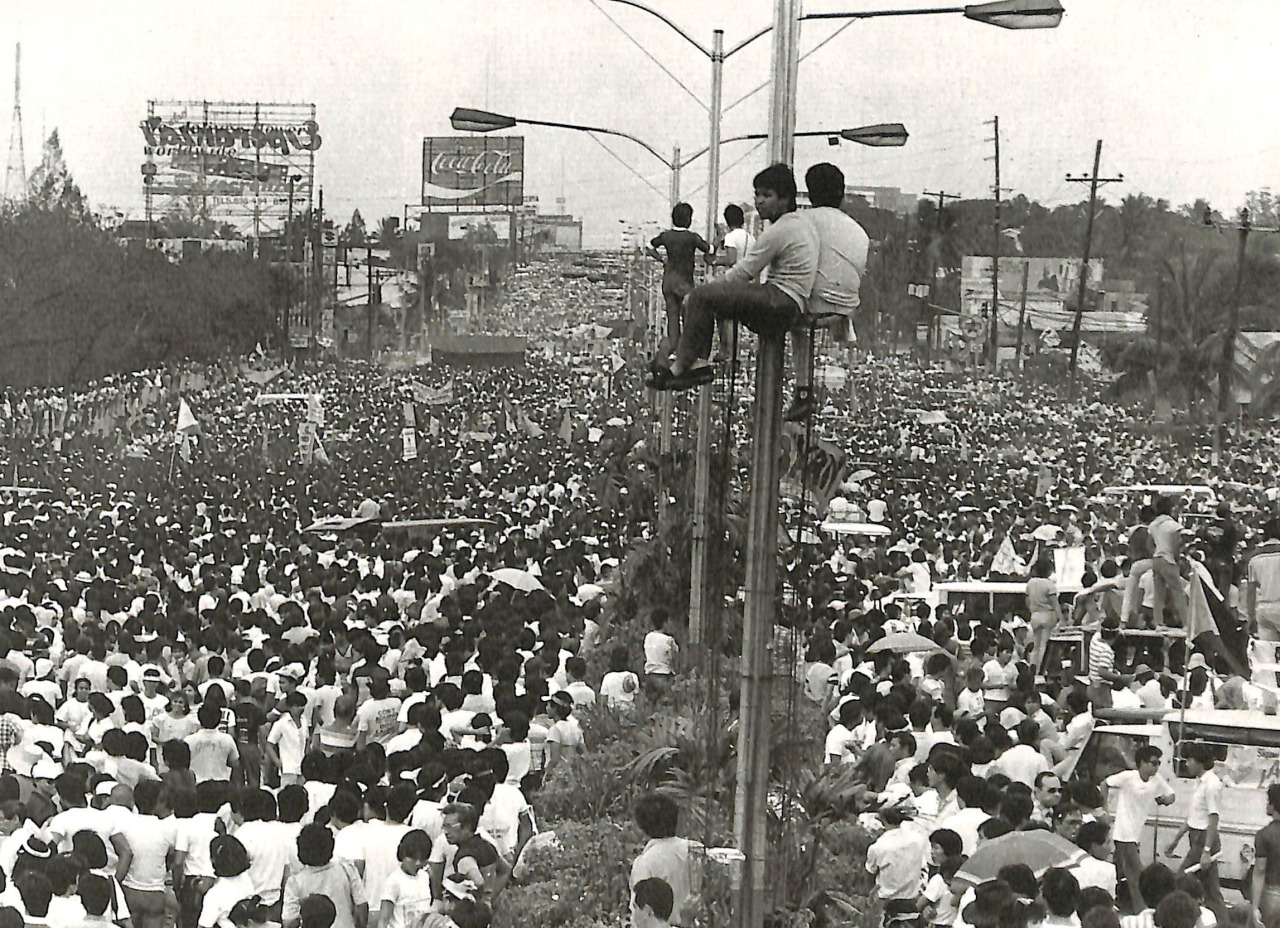

It has been 30 years since the EDSA People Power Revolution in the Philippines. Filipinos unified across the class spectrum to rid the Philippines of the Marcos family. Sectors of society that were traditionally at odds with each other such as the military, the church and the left overcame their differences to bring about a peaceful revolution. President Marcos and his remaining loyalists fled to Hawaii on a United States supplied plane once it became clear that his position was no longer tenable and that his ally Ronald Reagan was not going to ride to his rescue.

Marcos ruled the country from 1965 until 1986. Between September 1972 and February 1986 the Philippines was governed under martial law. Under martial law Marcos’ political opponents were dealt with by torture, incarceration, assassination, co-option or exile. In 1983 his archrival former Senator Benigno Aquino II returned to Manila from exile in the United States under an assumed identity. He was shot as he disembarked from the plane. It is widely believed, but has never been proven, that the Marcoses were behind the assassination plot. In due course Aquino’s assassination triggered the protests that eventually saw his wife, Corazon (Cory) Aquino, take center stage as Marcos’ nemesis in 1986 when she assumed the presidency after his departure.

Fast forward to 2016 and Aquino’s son, President Benigno ‘Noynoy’ Aquino III, is the outgoing president of the Philippines and Marcos’ son, Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos Jr., currently a Senator, is standing for the vice presidency. If Bongbong wins in May, and thus far the signs are favourable, he will be within a hair’s breath of the presidency.

For the Aquinos and the Marcoses the election is personal. President Aquino used his speech at the recent EDSA 30 anniversary to warn the public that Marcos, if elected, would become a dictator like his father. Marcos is on record as saying that he has nothing to apologize for in relation to his families’ human rights record and that Aquino should ‘move on’. He is also promoting a revisionist history of his father’s tenure in office by claiming that this was a golden age of order, prosperity and infrastructure projects that were actually completed. This message has found fertile ground with young Filipinos many of who face a daily commute of around six hours across Manila’s gridlocked metropolis. This has led to the #NeverAgain social media campaign that aims to educate young people on the atrocities of the Marcos years.

Consequently the options for the future governance of the Philippines are being articulated on the basis of a family dispute. The real tragedy for the electorate is that this far from unusual. Political dynasties dominate politics in the Philippines. The vested interests of a narrow group of families dominate the running of the country. Checks and balances, such as limits on the number of terms in office an individual is allowed to serve, are in place. These are designed to counter political fiefdoms but they are easily circumnavigated as political office is passed from husband to wife and parent to child. Political bailiwicks remain loyal to their local heroes and behind the scenes wealthy ‘kingmakers’ dole out election funds to their favoured candidates. Nevertheless, notwithstanding any irregularities in the electoral process, these elite families still need to appeal to the masses in order to stay in office. All politicians make a concerted appeal to the poor during their campaigning as the ‘ABC’ classes account for only 10% of the population. This means that politicians have to appeal to the D and E classes in order to gain enough votes to win.

Inequality is so extreme in the Philippines that Pope Francis called it scandalous during a visit to the Philippines in early 2015. Self-rated poverty ‘mahirap’ has virtually always been reported at over 50% since 1983. When Cory Aquino left office in 1992 poverty rates were only marginally lower than when Marcos left. In both cases this was over 70%. In 2010 Noynoy Aquino campaigned on a ticket that promised a reduction in both poverty and corruption. However his administration has not reduced poverty at all, according to self -rating. It was around 50% in 2010 and it is still around 50%. However Philippine GDP averaged 6.2% over Noynoy’s presidency. The Philippines was the second fastest growing economy in the world in 2015. So why do the most impoverished sector of the electorate see little or no change in their circumstances?

Figures show that income share (as a percentage) improved most amongst the middle and upper middle classes in the Philippines between 2006 and 2012. The middle classes, even at the lower end, tend to be relatively content and as such the possibility of a cross class revolution like that seen in 1986 is unlikely. Meanwhile the income of the most impoverished did not improve much, if at all. This begs the question of why the poor don’t vote en masse for national politicians that will promise to do something about their situation and deliver on that promise.

In reality the options available to voters are constrained. Virtually all the alternatives are drawn from an elite group that offer nothing in the way of ideological commitment or meaningful policy alternatives. Consequently Filipinos tend to vote on the basis of personalities as opposed to policies. This explains why the Philippine administration is littered politicians that have previous or even concurrent careers as sportsmen and television and movie stars. Filipinos are often derided for voting ‘stupidly’ or being bobotante but better voting surely entails better candidates. Win or lose Bongbong Marcos’ election result will enter the mythology of the Marcos/Aquino feud. However this feud is irrelevant to the needs of the poor and highly unlikely to make a difference to their daily struggle to exist.

Pauline Eadie is an Assistant Professor at the School of Politics and International Relations. This article forms part of IAPS continuing coverage of the 2016 general election in the Philippines. Image credit: Wikipedia Commons.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply