March 5, 2015, by Katharine Adeney

A new political turn for Indian Kashmir

By Dr Andrew Whitehead

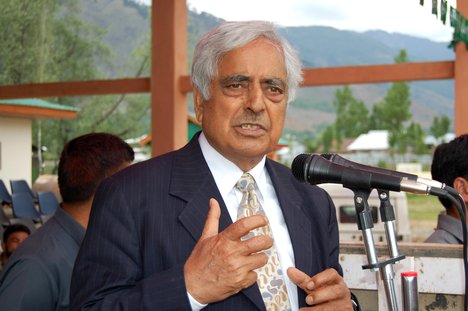

The 79-year old Mufti Mohammad Sayeed was sworn-in on Sunday (1st March) as the new chief minister of the Indian state of Jammu & Kashmir. Attending the ceremony in the state’s winter capital of Jammu was India’s Prime Minister, Narendra Modi. For his party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), it was a landmark moment. For the first time, a party often described as Hindu nationalist is in power in Jammu & Kashmir, India’s only Muslim minority state and its most disaffected.

Mr Modi campaigned hard in the state elections, coming to Srinagar, the main city of the Kashmir valley, where he addressed a rally wearing a pheran, the cape-like garment which is as Kashmiri as you can get. The BJP’s self-declared aim was Mission 44 – to gain forty-four or more seats in the state assembly which would give the party an overall majority. They fell a long way short, and are junior partners in the new state government to Mufti Sayeed’s People’s Democratic Party (PDP). But they now have a toehold in power in the state.

The political geography of Jammu & Kashmir is complex. In Jammu, which has a Hindu majority, the BJP took 40% of the vote and two-thirds of the area’s seats in the state assembly. But in the Kashmir valley, the overwhelmingly Muslim heartland of Kashmiri culture, it was a very different story. The BJP got about 2% of the vote and won no seats – though an allied party, headed by a former separatist, did have some modest success.

The overwhelming victors in the Kashmir valley were the PDP, supplanting the National Conference of the outgoing chief minister Omar Abdullah (his grandfather, Sheikh Abdullah, was the commanding Kashmiri political figure of the last century) which was seen as not delivering on better governance and flawed in its response to the devastating floods which deluged Srinagar last September.

But the PDP had campaigned to keep the BJP out of state politics, and as Mufti Sayeed commented on the eve of his inauguration, these two parties joining forces in a coalition government is like “bringing together the North Pole and the South Pole”.

Mr Sayeed is one of the few Kashmiri politicians to have held senior ministerial roles in India’s national government – he was home minister (the first Muslim to hold the office) in the late 1980s. He is a substantial political figure. The deal his party has done with the BJP took two months to negotiate.

The new chief minister appears to have won on his insistence that Jammu & Kashmir keeps its special status in the Indian constitution. Although this is of more symbolic than real importance, the BJP has had to set aside a key political goal in acquiescing to the continuance of what’s known as Article 370. Mr Sayeed has had less success in tackling the legal immunity for the Indian army which has been such a contested issue in Kashmir. The BJP has simply agreed to a review of the issue.

Mufti Sayeed also argued that moderate Kashmiri separatists (who don’t contest elections) need to be included in dialogue about the region’s future. During his previous term as chief minister – on that occasion in alliance with the Congress Party – he talked of applying a ‘healing touch’ in Kashmir. That’s certainly needed. Since a separatist insurgency erupted in 1989, about sixty-thousand people – some say considerably more – have been killed in the conflict.

Levels of violence are now much lower, though many young Kashmiris remain deeply disaffected with Indian rule. Both India and Pakistan claim Kashmir, and the former princely state has been divided between the two since 1947 though with India having the larger part. When I was in Srinagar last year, a Kashmiri whose opinion I respect said that while more Kashmiris supported Pakistan than India, most wanted independence above all.

Independence isn’t on offer, nor is there any prospect of the plebiscite to allow Kashmir self-determination which has been talked about for almost seventy years. But Mr Sayeed argues, somewhat pragmatically perhaps, that by forming a government with the BJP, India’s governing party will be forced to engage more actively with the realities of Kashmir and its problems and concerns.

A sign of the difficulties the new coalition government will face came within hours of the swearing in. The new chief minister expressed appreciation that Pakistan and Kashmiri separatists had not disrupted the recent voting in the state – a remark which predictably drew a furious response from BJP leaders, and indeed many other quarters. You should be thanking the polling staff and the Indian security forces, they said, not those who have fought against India.

The coalition agreement between the PDP and the BJP, however, is remarkable in addressing directly the need for a better relationship between India and Pakistan and reconciliation both within Jammu & Kashmir and between the Indian and Pakistan-ruled areas of the former princely state.

Not many local political deals have such lofty aims. The people of Kashmir will be waiting to see if this is simply rhetoric or has real substance.

Dr Andrew Whitehead, a visiting fellow at IAPS and author of A Mission in Kashmir, looks at the prospects for the new government in the Indian state of Jammu & Kashmir, and what it might mean for the long-running dispute over the status of Kashmir:

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply