November 2, 2014, by Esther Eidinow

Enjoying Receptions of Athenian Tragedy

Larissa Ransom, who is studying for an MA in Classical Literature, has recently seen Pilot Theatre’s Antigone, National Theatre Live’s Medea and Broadway Theatre Archive’s Antigone. Here she muses on how this has changed her thinking about Greek tragedy…

It is commonly believed that much of a book is lost when turned into a film. Greek tragedy was not intended to be read, but performed. And yet it is through reading, not viewing, that many of us are first introduced to the genre. I first encountered tragedy in the Penguin translations during my A Level years, in the ladybird-infested classroom in the damp attic of my old school. The words the translator chose, the voices of my fellow classmates, and my own imagination were the vehicles I used to discover Euripides’ Medea and Sophocles’ Antigone for the first time. Through reading I formed my first impressions of the plays, their themes, and their characters.

To see the plays in performance—to witness the words combined with action—is to see the genre in a whole new light. It enables you to notice things you did not before. I am now able to appreciate the humour hidden amongst the tragedy: a refreshing experience.

However, as often happens when I see a book transformed into film, when I watched these performances, I also felt much was lost, and my initial reaction was to recoil from them. Much was added to the plays, themes exaggerated, scenes and characters omitted, which made something so familiar to me into the unfamiliar. It was no longer how I saw the plays but how another had experienced and interpreted them. It was not subtle and it was not like reading scholarly literature on the genre. With plays in performance you cannot dip in and out of them at your own pleasure. You are fully immersed in the experience: the spotlight is on the actors and their actions, sound—words and music—envelops you and draws you in, and you can feel the tension of the audience around you as the drama approaches its climax. The different interpretation of the play is thrown right at you, with complete disregard for your own views.

Yet, I soon discovered, to see something unfamiliar made out of the familiar is not unenjoyable. I may disagree with the way Medea’s exit was staged in the NT’s version, but that does not mean I was not emotionally involved in the action.

The trick is to allow myself to let go of being a scholar, a classicist, a reader of the text, and allow myself, for the two hours of performance, to enjoy the play as if it is something new. For it is something new: a new twist on something old. And that doesn’t make it bad, just different.

And it is OK to disagree with the differences. But it is also OK to enjoy yourself, to enjoy the play before you now, as contradictory as that sounds. It is OK to ignore your memory of the text, to ignore that little voice, somewhere in the back of your head, pointing out to you that a flying chariot would have been more accurate—more faithful to Euripides’ version of the play—and, perhaps, more awesome.

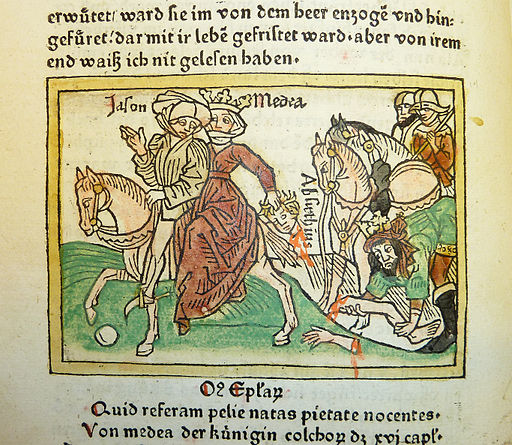

Image: Woodcut illustration (leaf [d]2v, f. xxij) of the escape of Jason with Medea and the death of her brother Absyrtis, hand-colored in red, green, yellow and black, from an incunable German translation by Heinrich Steinhöwel of Giovanni Boccaccio’s De mulieribus claris, printed by Johannes Zainer at Ulm ca. 1474 (cf. ISTC ib00720000). Penn Libraries call number: Inc B-720.

By kladcat [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply