October 5, 2014, by Esther Eidinow

‘Pitying Oedipus’

In our first Classics research workshop (also a Classical Association Lecture), Professor Patrick Finglass spoke on ‘Pitying Oedipus’; Professor Alan Sommerstein was inspired to offer this response…

Professor Patrick Finglass kicked off the new semester on Tuesday 30 September with a talk in his usual sparkling style to the Nottingham branch of the Classical Association on “Pitying Oedipus”. This title is crafted to be ambiguous: “pitying” can, and should, be taken both as a participle with Oedipus as its subject (“Oedipus taking pity”) and as a gerund with Oedipus as its object (“taking pity on Oedipus”).

Sophocles’ Oedipus the King begins with a scene of supplication. Nothing unusual in that, in itself, but these suppliants are not, like most suppliants in tragedy, begging a foreign ruler for an exceptional favour which it may be perilous to grant: they are asking their own king to do something plainly within his normal job description, namely protect them (from the ravaging plague), and what is more, it turns out that he has already taken action before being asked, by sending his brother-in-law Creon to seek guidance from the Delphic oracle. Evidently Sophocles created this scene in order to show Oedipus as a wise, efficient and caring ruler, and especially, so Patrick argued, as one who pities the sufferings of his people. He addresses them as “my pitiable children” (line 58), and says that “my soul groans for the city, for myself and for you” (lines 63-64). Accordingly, when he learns that Apollo has told the Thebans that they can end the plague only by killing or banishing the murderers of Laius, Oedipus with inflexible determination seeks them out …

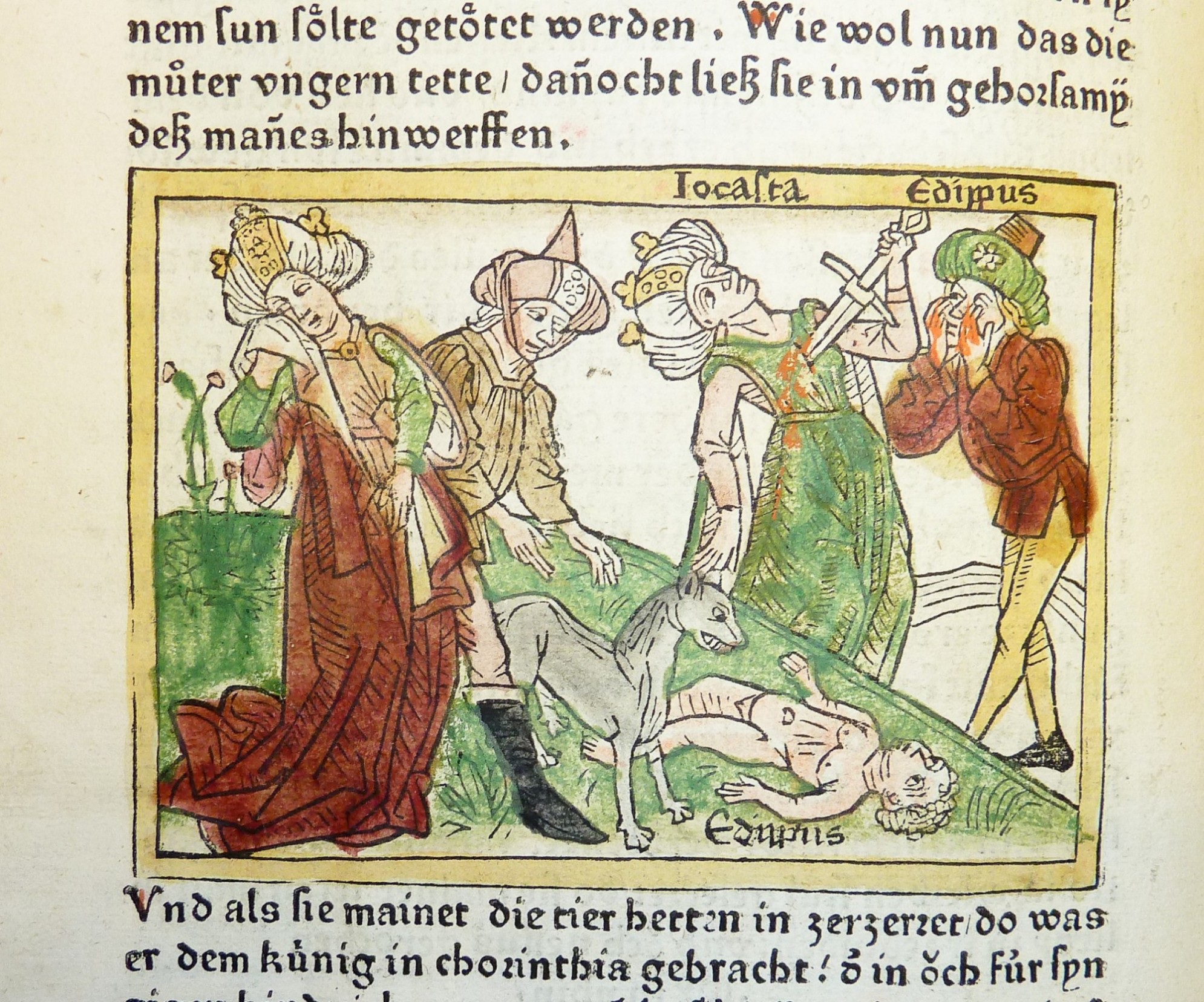

… to discover in the end that there was only one murderer, and that it was himself; and furthermore, that Laius was his father, and Iocaste, Oedipus’ wife and mother of his four children, is also Oedipus’ own mother. And at the moment when the truth is finally revealed, we hear about pity again.

Oedipus has summoned to his presence the shepherd (Shepherd A) who is the sole surviving eyewitness of the murder of Laius. Before he arrives, however, Oedipus’ interest and everyone else’s has shifted to the topic of Oedipus’ own origins, as he is told that he is not, as he had thought, the son of King Polybus of Corinth, but had been brought to Corinth, as a baby, by a shepherd (Shepherd B) who had received him from … Shepherd A. So Shepherd A finds himself being questioned about this episode, and does all he can to avoid answering, until he is threatened with torture. Then, as slowly as possible, he brings it out: the baby came from Laius’ palace, was said to be his own son, and was given to Shepherd A by Iocaste with instructions to kill him, because an oracle had said the child would one day kill his parents. At which Oedipus cries out “Iou, iou, it all comes out clear! May I never look on the light of day again!” and rushes into the palace. Except that he doesn’t. Instead he asks a seemingly unnecessary question: “How come you let the child go by giving him to this man?” And the shepherd replies in what Patrick finds the most gut-wrenching words in Greek tragedy (alternative proposals gratefully received):

Because I pitied it, master. I thought he would take it to another country, where he came from. And he saved it – for the greatest of miseries. Because if you’re who he says you are, then I tell you you were born for an evil fate (1178-81).

His kindness has led to utter catastrophe – and the tale is not yet complete. In an echo of these words, Oedipus later says that he would never have been saved from death “if not for some terrible evil” (1457), and the context shows that he is speaking of an evil that has not yet happened. David Kovacs has persuasively argued that Sophocles’ audience will think of Oedipus’ later curse upon his sons, which led to the war of the Seven against Thebes in which those sons killed each other.

Oedipus the baby was shown pity. Oedipus the king showed it. Oedipus the blinded wretch, at the end of the play, both pities and is pitied. He is pitied by Creon (1473) who brings out to him his two daughters, Antigone and Ismene, to whom he speaks movingly of the sad lot that awaits them, excluded from social and religious activities and from the prospect of marriage; he begs Creon to pity them (1508) and care for them as he himself no longer can. But the more lovingly he speaks, the more we will pity him, knowing, as he does not, what is going to happen. Not only will Oedipus’ sons die at each other’s hands; one of his daughters, Antigone, will die by her own hand, after having been buried alive in an underground chamber – by Creon’s order. Sophocles had memorably dramatized (and perhaps largely invented) that story ten or fifteen years before. In Oedipus the King Sophocles repeatedly plays on an association between Oedipus’ name and the verb oida “I know”. At one moment the king sarcastically calls himself “know-nothing Oedipus” (397), meaning the opposite (he knew the answer to the Sphinx’s riddle, which no one else did). But “know-nothing” is in fact all too accurate. He did not know whom he was killing; he did not know whom he was marrying; he does not know to what a fate he himself will condemn at least three of his four children. And all because someone pitied him enough to disobey an order to kill him.

Image: “Woodcut illustration of Jocasta and her son Oedipus – Penn Provenance Project” by kladcat – Woodcut illustration of Jocasta and her son Oedipus. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Woodcut_illustration_of_Jocasta_and_her_son_Oedipus_-_Penn_Provenance_Project.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Woodcut_illustration_of_Jocasta_and_her_son_Oedipus_-_Penn_Provenance_Project.jpg

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply