April 28, 2014, by Richard Rawles

CA report: Legacies of Greek Political Thought in America

CA conference: Legacies of Greek Political Thought in America

Nottingham PhD student John Bloxham reports on a panel at the recent CA conference in Nottingham.

For a postgraduate student, of a nervous temper, being asked to convene a panel was cause for a little anxiety. But with the panel taking place at the Classical Association’s annual conference (the Wimbledon of the classics conference circuit), my jitters were perhaps justified. I knew the calibre of speakers and papers would be high and that there would be a lot to live up to. Conversely, it is a prestigious conference, so getting high quality speakers to join the panel was easier than I had foreseen.

Nottingham’s Classics Department is strong in reception studies and a member of the Legacy of Greek Political Thought group, and I convened a panel on their behalf. The challenge was to provide a narrow enough focus that the four papers provided an integrated and coherent narrative, while still appealing to a varied audience of classicists. I focused the panel on American receptions of Greek political thought, which fitted closely with my own research. The aims of the panel were to examine and challenge the links between ancient Greek political thought and its modern invocations in the United States.

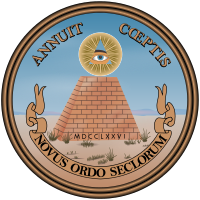

The reverse of the Great Seal of the United States is a reminder of the Founding Fathers’ ambition to create ‘A New Order of the Ages,’ unlike any previous society. Yet correspondence between the Founders shows a keen awareness of and engagement with past societies. In ‘Is there space for a Greek influence on American Thought?’ Nicholas Cole (Oxford) considered the American revolutionary period and addressed this paradox head-on. Nicholas argued that Greek history and thought made important contributions to American thinking, and that these help to explain the development of American thought in the early republic. But historians need to move beyond the narrow debate on political borrowings towards an appreciation of the wider multiplicity of ways that early Americans engaged with Greek thought.

Vaulting forward to the twentieth century, Sara Monoson (Northwestern) explored contrasting attitudes to antiquity in ‘Classical sources and the promotion of literacy in radical critique: Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads (1933) and Hugo Gellert’s Aesop Said So (1936).’ Her paper focused on the presence of classical imagery in 1930s expressions of radical critique by visual artists. In his controversial mural for the Rockefeller Center in New York, Diego Rivera used the imagery of damaged yet formidable classical statuary to suggest the corrosiveness of weighty traditions and to question the value of harking back to antiquity. Though sharing his political viewpoint, Hugo Gellert challenged that view of antiquity. He produced books that combine text and illustrations to find other narratives in the sources (chiefly, the figure of Aesop as a view ‘from below’) that were, to him, able to inspire class consciousness and a sophisticated examination of problems like the greed and corruption of the high and mighty.

In the first of two papers looking at the conservative thinker Leo Strauss, Liz Sawyer (Oxford) presented ‘Leo Strauss, in context: Classical Literature as Political Philosophy in 1950s/1960s American Universities.’ She examined how Strauss’ use of classical literature, especially Aristotle, Plato and Thucydides, fitted within the broader context of how political philosophy and Western literature were taught in the 1950s and 1960s. By studying Strauss’ writings in the light of the educational methodologies of his time, Liz demonstrated how Strauss’s legacy as the ‘founding father’ of today’s neoconservative movement developed. In the final paper, ‘The original neoconservative? Leo Strauss’s version of Xenophon’s version of Socrates,’ I argued that Strauss’s interpretations of Xenophon have been overlooked by political commentators seeking to praise or malign the Straussian influence on American politics. Using Strauss’s commentary on Xenophon’s Oeconomicus as a case study, I argued that Xenophon, rather than Plato or Thucydides, is the classical key for unlocking Strauss’s political ideology.

The focus on Greek thought in America gave the panel coherence, whilst differences in the subject matter and methodological approaches of the speakers ensured variety. Each of the other papers gave me fresh insights into my own work, and the discussions which followed were almost as fruitful as the papers themselves (and gave no indication that any audience members might have over-indulged at the previous night’s gala dinner). Having spent the build-up to the conference worrying about my own paper, which passed in a flash, it is only in retrospect that the real benefits of attending a conference like this became apparent – the unexpected connections and the perceptive and creative conversations with fellow delegates made attending this CA conference an enriching experience.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply