November 22, 2017, by Helen Lovatt

Enoch Powell and the Classics

Gary Fisher on Herodotus, Enoch Powell, and Metaphors of Arboreal Rebirth

‘In that acropolis [of Athens] is a shrine of Erechtheus, called the “Earthborn,” and in the shrine are an olive tree and a pool of salt water. The story among the Athenians is that they were set there by Poseidon and Athena as tokens when they contended for the land. It happened that the olive tree was burnt by the barbarians with the rest of the sacred precinct, but on the day after its burning, when the Athenians ordered by the king to sacrifice went up to the sacred precinct, they saw a shoot of about a cubit’s length sprung from the stump, and they reported this.’

The above passage of Herodotus’ Histories (8.55) recalls an episode from the second Persian invasion of Greece, shortly after Xerxes’ sack of Athens in 480. It discusses the fate of an olive tree on the Athenian Acropolis, allegedly placed there by Athena herself, that had come to serve as a symbol of the city and the Athenian people. After Xerxes’ invasion of the city a party of Athenians are described as ascending the razed Acropolis to discover that, despite the destruction, a shoot of new life had emerged from the burnt husk of this tree. Just as this olive tree was able to grow new life in spite of seemingly total destruction, so too will the Athenian people it had come to symbolise. As with much of Herodotus the historicity of this episode has been doubted, yet this episode is perhaps more interesting for its life beyond the pages of Herodotus, particularly with regards to its reception in post-war British politics.

Enoch Powell and Herodotus

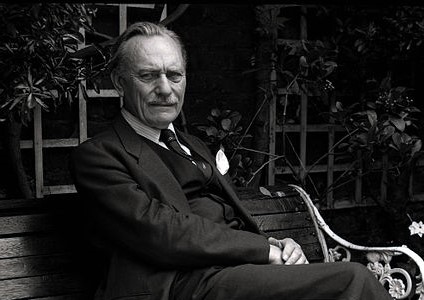

John Enoch Powell is perhaps best, and to some solely, known for his 1968 ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech. His life and writings have been subject to much academic scrutiny, most of which has focused on his political career during the late 1960s and 70s. Yet, long before he delivered the speech that would define him for posterity, Powell had a lively, and highly successful, career as a classicist. After graduating with a double first from Cambridge, Powell published various commentaries and translations of Herodotus, served as curator of the Nicholson Museum, and was appointed as a Professor of Greek at the University of Sydney at the age of twenty five, only just failing in his aim of beating Friedrich Nietzsche’s record of becoming a professor at twenty four. This inculcation in the classics is evident in Powell’s political life: most famously, in his ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech Powell compares himself to the Roman, seeming to see ‘the Tiber foaming with much blood’. Yet Powell’s studies of Herodotus, and in particular of the passage introduced at the start of this post, also make an appearance in his political career.

It is in a speech to the Churchill Society on St. George’s day of 1961, just over a year after Harold Macmillan’s landmark ‘Winds of Change’ speech that heralded the mass decolonisation of Africa, that Powell introduced this episode from Herodotus to his audience. Comparing post-colonial Britain to Athens after Xerxes’ destruction, Powell described how the Athenians in Herodotus 8.55 ‘alive and flourishing in the blackened ruins, the sacred olive tree, the native symbol of their country. So we today, at the heart of a vanished empire, amid the fragments of demolished glory, seem to find, like one of her own oak trees, standing and growing, the sap still rising from her ancient roots to meet the spring, England herself.’

Powell is deploying his classical education to understand, and influence how his peers understand, Britain’s place in an increasingly postcolonial world. In Powell’s analogy the razed city of Athens is replaced with the newly independent colonies of the British Empire, and the new life of Athena’s Olive tree is updated to the annual springtime rebirth of the characteristically English oak, but the theme is the same. Powell, like Herodotus’ Athenians, looks to the arboreal rebirth of a symbol of his people as a means to find, and inspire, hope for the future. Powell had read in Herodotus how the Athenians looked to the new life in Athena’s Olive tree as a symbol of hope for their people. He now urges his own countrymen, who in the former Empire occupied themselves with ‘distant continents and strange races’, to now turn their gaze back to their own Albion Oak, which after Winter draws sap up from its ‘roots in English earth’, as a model to face this new era. To Enoch Powell the classical tradition, just like Athena’s tree on the Acropolis, was very much alive.

A transcript of Powell’s speech can be found at http://www.churchill-society-london.org.uk/StGeorg*.html

The writer of this reprehensible piece should be deeply ashamed of herself in justifying Enoch Powell’s vociferous racism, imperialism, and xenophobia. There’s nothing pulchritudinous or commendable in Powell drawing parallels with Herodotus and Vergil to mourn decolonisation as a near-dearth upon the English people, immigration from Africa and Asia to the UK as ushering in ‘rivers of blood’ (Aeneid VI), among Powell’s other archaic and disgusting views.

Dear Brian,

My apologies for any upset my post has caused, that was certainly not my intention in writing it.

I first feel compelled to ensure that your anger is directed towards the correct recipient. Your use of ‘herself’ suggests to me that you have mistaken the uploader of the post, Helen Lovatt, for the author, Gary Fisher, as is indicated in the brief preface to the post that appears beneath the title.

I can assure you that it was not my intention with this post to suggest there was anything ‘pulchritudinous or commendable’ in Powell’s use of the classical world in his 1961 St. George’s Day speech. I do however believe that, given Powell’s significance in post-war British political history, the influence that his classical education had upon his later political career is an important case study in the reception of the ancient world. Regardless of how archaic and disgusting we may find his views, Powell and his use of the ancient world are a part of the dialogue on the classical tradition and thus ought to be subject to examination.

Sincerely,

Gary Fisher

Oh dear “Powell is deploying his classical education to understand, and influence how his peers understand, Britain’s place in an increasingly postcolonial world.”

No he is not!

He is arguing for colonial amnesia – that the extensive harms of Britain’s imperialism had somehow not impacted on England which had, despite its crimes against humanity, remained ‘uninvolved’ and somehow innocent and pure. It was not only dishonest and attempting to wipe away centuries of history but was designed, underneath the veneer of classical scholarship, to promote a racist, nativist, politics of exclusion. It was an attempt (sadly not completely unsuccessful) to deny any responsibility for the underdevelopment of Britain’s colonies and to promote racist exclusionary policies in the metropole towards the descendents of colonised people.

Btw your link to the speech is broken.