April 1, 2015, by Oliver Thomas

The Night Raid

Helen Lovatt considers Caroline Lawrence’s The Night Raid and writing about the classical world for children.

Several people in my Independent Second Year Project group have decided to write for an audience of children. We have been discussing how this can make a difference to your writing in both style and content. For instance, one project is about Roman magic. Can you include love magic? What about demeaning images of witches? What about violent scenes? Lucan’s Erichtho who kisses a corpse to pull out its tongue – probably not on? Canidia, who sacrifices a young boy in Horace Epode 5?

An interesting case study on this, and on how you write differently for less able readers, is Caroline Lawrence’s reworking of Aeneid 9 for dyslexic teenage boys. The Night Raid is designed to engage older reluctant readers by tackling difficult subject matter in simple language. The Aeneid is not often adapted for children – much less often than the Odyssey, although another honourable exception is Blood of Wolves by Sulari Gentill, which my nine-year-old daughter has read many times. In particular, the Nisus and Euryalus episode is difficult both for its violence and its latent sexuality. Their mutual death-in-love is the climax of the episode.

Lawrence’s discussion of the writing process makes some specific stylistic points which my students might find helpful: paraphrase difficult words; rewrite adverbs with verbs; have a killer first paragraph. The simplification of names (‘Rye’ for Euryalus; ‘the Leader’ for Aeneas) is a tactic also used by Sulari Gentill, three of whose main characters are Mac (Machaon), Cad (Cadmus) and Ly (Lycon).

The ‘killer first paragraph’ is particularly interesting for me. Lawrence’s opening consists of very short paragraphs – at most three sentences, some just two or three words. It also replaces ideals of heroism with the reality of death and pain. The book is anti-epic in many respects: not just in its length and tight focus, but also in its grit.

It certainly does not hold back on the violence. The story begins at the fall of Troy, with Nisus encountering Euryalus with his dead father – a small boy already determined to take revenge. The narrative arc of the episode is fundamentally changed by taking it back this far. Their love is the love of one young boy for another, and the story is more about the cost of revenge than love and the desire for glory. Rye’s first killing, of a man who ‘vomits up his life spirit along with scarlet blood and purple wine’ (p.58), is linked back to Nisus’ memory of their first meeting.

Juliette Harrisson argues in her review that the interpretation of Nisus and Euryalus’ relationship as friendship or a sexual relationship is left open by both Virgil and Lawrence. But that was not how I read it: Euryalus is beautiful, yes, and Nisus talks of his ‘lovely head’ as Virgil’s poppy simile is focalised through him, but in his last speech Nisus calls him ‘Little Rye’ and ‘my friend’. As they reunite in the afterlife, Nisus describes Euryalus as ‘A Trojan. And my friend.’ They hold hands and are happy to be together for ever, but there is no hint of any sexual love.

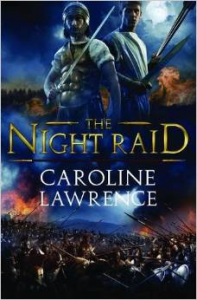

The presentation of the book is equally careful to avoid any hint of love as part of the story: the cover image is relentlessly military; although it features the pair together, they stand back to back, swords drawn. The tag-line on the inside fly-leaf reads ‘For Rye and Nisus, honour is everything.’ The back blurb sells the story as ‘a chance to win back their honour’ after the fall of Troy.

The presentation of the book is equally careful to avoid any hint of love as part of the story: the cover image is relentlessly military; although it features the pair together, they stand back to back, swords drawn. The tag-line on the inside fly-leaf reads ‘For Rye and Nisus, honour is everything.’ The back blurb sells the story as ‘a chance to win back their honour’ after the fall of Troy.

This is certainly a sophisticated and powerful retelling of the episode, made no less so by careful use of plain language and simple syntax. But as so often in children’s literature, violence remains much more acceptable than sexuality.

Images:

Top: Detail from Jean-Baptiste Roman’s Nisus and Euryalus (1827), © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons.

Right: Cover image from Lawrence’s blog (link above).

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply