April 25, 2014, by Helen Lovatt

Roman noses

Mark Bradley sniffs out the significance of noses for Romans and others.

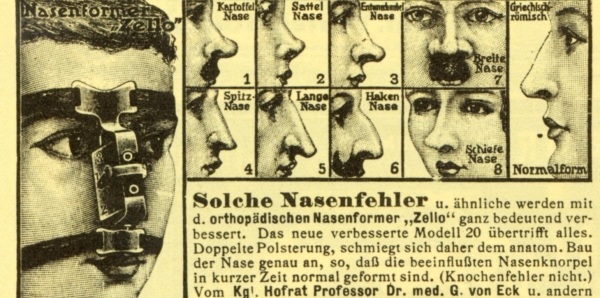

Go back a hundred years or so, and well-to-do men and women in Berlin could be very conscious about their nose-shape. Anyone who had a potato nose, saddle nose or duckbill nose, or one that was wide, pointy, long, hook or slant had good reason to feel excluded in the face of prevailing obsessions with the ideal Germanic appearance. But just before the outbreak of the First World War the German entrepreneur and marketing specialist Leo Maximilian Baginski came to the rescue with the ‘Nasenformer Zello’, an intimidating-looking but widely acclaimed metal contraption which sufferers could strap on to their face, and which over a period of time would mould the cartilage into the correct shape. That correct shape was described in the publicity flyers as the ‘Griechisch-römisch Normalform’ (the Greco-Roman ideal nose).

In Victorian England too, where the nose was considered ‘the strongest, highest, and most perfect expression of character, even in the face of a beast’, the Roman (or ‘aquiline’) nose was considered the most desirable type, a sign of great powers of decision, energy and firmness.

The nose – taking centre-stage in the face, the organ of smell and considered the most direct conduit to the brain – was arguably the most focalized (and certainly the most prominent) feature of the body. Protruding from the face, noses are the first appendages to reach the eyes of observers, the first to be burned by the sun, and the first to get knocked by a door, a fist or the floor: they were what made a face a face.

In every culture, noses carry a telling and pervasive set of properties and associations: they can be an index of race (the snub African nose, or the hooked Jewish nose); age (noses continue growing outwards until mid/late adolescence, and cartilage stretches and droops in the elderly); gender (male noses are typically longer and bonier than female noses); family (noses are an telltale index of genetic continuity); profession (boxers and fighters are typically identified by fractured or broken noses); and even class (the aquiline nose of nobility is surprisingly far-reaching, and aristocratic ‘bearing’ is often defined by an upturned nose). These patterns have been of perennial interest to thinkers, writers and historians, from the physiognomists and sculptors of the ancient world, through to the racial theorists of nineteenth-century Europe and the fashion industry of the twentieth-century west.

I have been sniffing my way around the topic of ‘Roman noses’ for over a year now, and have presented my findings to audiences at St Andrews, the Voglia d’Italia society, the annual conference of the Classical Association in Nottingham, and the ESSHC conference in Vienna. This research, which I am currently writing up into a journal article, marks the point where my work on ancient smell and foul bodies intersect. I have been looking at how the ancients thought the nose worked, as the organ of smell and as a gateway to the soul, as well as the site for expressing contempt, disgust, anger, distress and terror. I’ve also been thinking about how they classified different nose shapes and sizes and related them to people’s origins, character and behaviour: for one thing, it is striking how many Roman surnames (Cicero, Naso, Nasica, Silanus, Silo, Silus) evoked distinctive noses.

One of the most interesting aspects of this research has been to explore how all these complex ideas about noses played out in classical art, from portraits of gods and goddesses with a strikingly pronounced nasal bridge to the distinctive noses of Roman emperors who needed to stand out from the crowd, to Roman matrons sporting prominent ‘Roman noses’ (giving us cause to reconsider Pascal’s famous quote that ‘if Cleopatra’s nose had been shorter, the whole face of the earth would have been different’). In addition, the number of portraits with their noses missing – often deliberately smashed in or chiselled off – is staggering: on some level, power and authority appears to have resided in the nose.

If you want to see some of the portraits I’ve been looking at, then check out my Facebook photo album.

Image credits: Advertisement for the Nasenformer Zello (c. 1910).

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply